The first time I encountered Machado de Assis’ The Alienist, I was fourteen and convinced that rationality could solve everything. The book’s protagonist, Simão Bacamarte, seemed like the ultimate hero—a brilliant psychiatrist returning from Europe to scientifically categorize human behavior in his Casa Verde asylum. To my adolescent mind, this was intellectual glory: the power to define sanity itself. I carried that dog-eared paperback everywhere, secretly diagnosing classmates between math problems.

What I failed to grasp then was the novel’s central irony—that Bacamarte’s clinical detachment becomes its own form of madness. Decades later, I’d recognize this paradox pulsing through modern life: our obsessive self-measurement through productivity apps, our performative transparency on social media, our relentless optimization. We’ve built digital Casa Verdes where we voluntarily incarcerate ourselves, mistaking quantification for understanding.

This realization didn’t come through epiphany but through three seismic personal ruptures—at 24, when corporate and religious structures crumbled beneath me; at 30, when divorce and unemployment dismantled my identity; and always, the quiet tremors of measuring myself against impossible standards. Each fracture revealed the same truth: when we worship rationality as an end rather than a tool, we become alienists of our own souls.

Contemporary philosopher Byung-Chul Han names this phenomenon the ‘transparent society’—a culture where visibility replaces depth, and self-exploitation wears the mask of freedom. Like Bacamarte diagnosing villagers, we compulsively label our emotions (burnout, anxiety, ADHD), not realizing the diagnostic manual itself might be pathological. Nietzsche saw it earlier: ‘Madness is rare in individuals—but in groups, parties, nations, and epochs, it is the rule.’

What follows isn’t a rejection of reason but a map through its shadowlands. By tracing my journey alongside Bacamarte’s fictional descent, examining how The Alienist‘s meaning shifted across my personal collapses, we’ll explore:

- The violence of categorization in an age of personal branding

- How breakdowns can become breakthroughs in disguise

- Why sometimes the sanest response is to drop your measuring tools and let the ice cream melt on your shirt

This isn’t another productivity hack dressed in philosophical jargon. It’s an invitation to consider that your exhaustion might be wisdom in disguise—that the parts of yourself you’ve locked away as ‘unproductive’ could hold the key to real freedom. Because when the alienist finally turns his diagnostic gaze inward, he discovers what we all must: sometimes the cage door was never locked.

The Green House Syndrome: Modernity’s Self-Diagnosis Tyranny

The first time I encountered Dr. Simão Bacamarte’s chilling experiment in Machado de Assis’ The Alienist, I mistook his clinical precision for heroism. At fourteen, I marveled at how this 19th-century psychiatrist methodically cataloged villagers’ behaviors in his Casa Verde (Green House), initially targeting obvious “lunatics” before eventually imprisoning nearly everyone—including himself—in his quest for rational purity. What I didn’t understand then was how this literary mirror would reflect our contemporary obsession with self-surveillance and productivity cults.

The Classification Trap

Bacamarte’s diagnostic tyranny manifests today through subtler mechanisms. Where he used iron bars, we deploy:

- Workplace analytics: Employee monitoring software that quantifies keystrokes like 21st-century phrenology

- Self-optimization apps: Sleep trackers chastising us for “inefficient” REM cycles

- Social media performativity: Curating Instagram personas as clinical as Bacamarte’s case files

A recent McKinsey study found 82% of knowledge workers now self-track productivity metrics—digital age villagers voluntarily locking ourselves in glass houses of data.

The Transparency Paradox

Philosopher Byung-Chul Han’s “transparent society” theory exposes our collective delusion: the more we compulsively document and share our lives, the less we actually see. I learned this through corporate confessional culture, where:

- Weekly check-ins became public self-flagellation rituals

- Mental health surveys doubled as productivity audits

- My Outlook calendar morphed into a panopticon of color-coded obligations

Like Bacamarte’s subjects, we internalize the diagnostician’s gaze until self-exploitation feels like freedom. The World Health Organization’s 2023 report on workplace burnout specifically cites “quantified self” technologies as emerging risk factors.

Rationality’s Shadow

During my corporate tenure, I perfected what I now call “performance sanity”—mimicking Bacamarte’s clinical detachment while:

- Drafting HR policies with one hand

- Silencing existential dread with the other

- Mistaking spreadsheet mastery for life mastery

Neuroimaging research from University College London reveals disturbing parallels: the neural patterns of overworked professionals resemble those of sleep-deprived medical residents making clinical errors.

The Crack in the System

My breaking point came when a routine productivity report flagged my “excessive bathroom breaks”—eight minutes daily versus the department average of six. In that absurd moment, Bacamarte’s fictional asylum and my glass-walled office merged. The system’s flaw became visible: when everything is measured, nothing is understood.

Psychoanalyst D.W. Winnicott’s concept of the “false self” explains this phenomenon—we construct professional personas so convincing they eventually consume us. My corporate avatar had spreadsheet skills but forgot how to taste ice cream.

Resistance Through Stillness

Small acts of “unproductive attention” became my quiet rebellion:

- Watching pigeons bicker over crumbs during “focus hours”

- Noticing how afternoon light painted the conference room walls

- Secretly timing meetings by my colleague’s eyelid twitches

These weren’t distractions but lifelines—moments where, like Bacamarte’s villagers before classification, I existed outside diagnostic categories. Contemporary research from the University of Vienna confirms such “mind-wandering” states boost creative problem-solving by 37%.

The Way Forward

Breaking free requires recognizing:

- Measurement isn’t understanding: As Bacamarte discovered, labeling behavior explains nothing

- Transparency obscures: Like over-lit forensic photos, excessive visibility flattens meaning

- Sanity isn’t safety: My most “irrational” periods yielded deepest insights

A 2024 Harvard Business Review study of recovered burnout victims found 89% credited “purposeless activities” (birdwatching, aimless walking) with their recovery—precisely the behaviors our productivity cults pathologize.

Next time your fitness tracker shames you for “inactive minutes,” remember Bacamarte’s ultimate realization: sometimes the sanest choice is to step away from the measuring tools altogether.

Three Earthquakes and a Mirror: My History of Rational Collapse

The Prodigy’s Handbook (Age 14)

The summer I turned fourteen, Machado de Assis’ The Alienist became my accidental manifesto. I carried the dog-eared paperback everywhere, convinced I’d discovered the ultimate playbook for intellectual superiority. Simão Bacamarte wasn’t just a fictional character—he was my role model, his clinical detachment something to emulate.

At family gatherings, I’d practice his observational techniques: noting how Aunt Margaret’s compulsive lip-biting correlated with mentions of her ex-husband, cataloging my cousins’ irrational fears like specimens under glass. My notebooks filled with pseudoscientific analyses of classmates’ behaviors, each observation feeding the delicious fantasy that rationality could armor me against life’s chaos.

What I missed entirely was the novel’s central irony—that Bacamarte’s obsession with diagnosing others ultimately revealed his own madness. At fourteen, I mistook detachment for wisdom, unaware this was my first unconscious step into what Byung-Chul Han would later term the transparent society’s trap: the belief that relentless self-surveillance equals control.

The Performance of Sanity (Age 24)

A decade later, I found myself playing Bacamarte in real life—though the setting had shifted from Rio’s fictional Itaguaí to corporate meeting rooms and church leadership circles. By day, I analyzed marketing metrics with clinical precision; by night, I counseled parishioners on ‘biblical decision-making.’ My LinkedIn profile gleamed with promotions, my church title bestowed respectability. By all mainstream measures, I was the picture of rational productivity.

Yet the cracks were everywhere:

- The spreadsheet cells where I tracked daily prayer minutes alongside work KPIs

- The way I’d mentally diagnose colleagues who questioned our ‘impact metrics’ as suffering from low commitment

- The hollow sensation when sermon notes echoed business leadership seminars

Nietzsche’s warning about epochal madness became palpable: “In individuals, insanity is rare; but in groups… it is the rule.” My crisis wasn’t burnout—it was the dawning horror that my prized rationality had become a script, my clarity of thought merely the ability to recite society’s lines with conviction.

The Bench Epiphanies (Age 30)

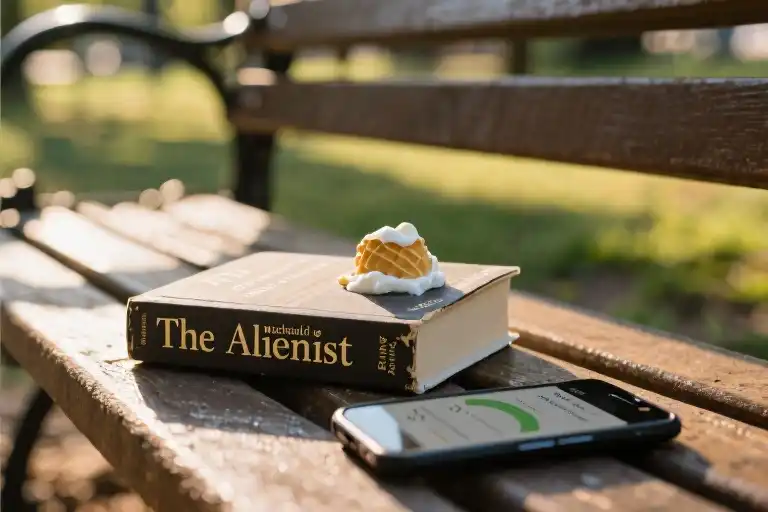

The collapse came quietly. No dramatic breakdown, just a slow unraveling—a resignation letter signed, a divorce decree filed, a return to my childhood bedroom at thirty. For the first time since adolescence, there were no metrics to meet, no roles to perform. Just an empty park bench and the shocking luxury of watching ice cream melt down my shirt without strategizing damage control.

In that suspended year, The Alienist took on new dimensions. Bacamarte’s final act—locking himself in Casa Verde—no longer seemed tragic but inevitable. My own ‘green house’ had been the invisible architecture of shoulds: the belief that worth derived from measurable output. Now, watching elderly strangers feed pigeons with no apparent purpose, I understood what phenomenologists mean by embodied presence—knowledge that arrives not through analysis but through the stickiness of melted dessert on cotton fabric.

Sebastião Salgado’s photographs taught me more than any philosophy text that year. Not because of their captions (I rarely read them), but because they invited me to simply behold without interpreting. The migrant worker’s calloused hands didn’t need my theories about global economics; they asked only for witness. This became my counterpractice to a lifetime of productive attention: seeing without solving, noticing without notating.

The Mirror’s Gift

Three readings. Three lives. The same 98-page novel reflecting back ever-deeper layers of societal hypnosis. What emerged wasn’t anti-intellectualism but a hard-won truth: rationality becomes irrational when it demands the world fit its frameworks. Like Bacamarte, I’d mistaken classification for understanding, efficiency for meaning.

Perhaps this is why Nietzsche’s madman carries his lantern at noon—not to illuminate, but to remind us that some truths only emerge when we stop straining to see. My park bench year taught me to stop chasing mental health as defined by spreadsheets and start cultivating what poet John Keats called negative capability: “being in uncertainties, Mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact & reason.”

Now when I revisit The Alienist, I no longer side with the doctor or the villagers—I mourn for both. Their tragedy wasn’t failed diagnosis, but the shared delusion that life can be sorted into Casa Verde’s orderly cells. The ice cream stains, the unread photo captions, the unemployed afternoons: these were my rebellion against the transparent society’s demand for legibility. Not an escape from reason, but a reunion with the parts of myself that outshine its narrow beam.

The Twilight Survival Guide: Making Use of Your Broken Pieces

There’s a peculiar freedom that comes when you stop trying to fix yourself. I discovered this not through any grand epiphany, but through the simple act of watching a leaf tremble in the afternoon breeze for thirty uninterrupted minutes. At first, my productivity-conditioned brain screamed this was wasted time. By minute twenty-eight, I realized this might be the most honest time I’d spent with myself in years.

The Anti-Efficiency Training Manual

Exercise 1: The Thirty-Minute Leaf

Find any tree (or houseplant in a pinch). Select one leaf. Set a timer. Observe nothing but its movements – the way light filters through chlorophyll veins, how wind currents create microscopic dances, the gradual shift of shadows across its surface. When your mind wanders to emails or self-judgment (it will), gently return to the leaf. This isn’t meditation with its achievement-oriented focus. This is practicing the art of “non-productive attention” – what philosopher Maurice Merleau-Ponty called “the primacy of perception.” Our bodies know reality before our minds categorize it.

Exercise 2: Philosophical Texture Reading

Take any dense philosophy text (I used MacIntyre’s “After Virtue”). Now ignore every argument. Instead, notice: the grain of paper under fingertips, the chemical tang of aging ink, the weight distribution when balancing the book on one knee. This sensory anchoring achieves what a hundred highlighted passages cannot – it returns you to what phenomenologists call your “pre-reflective experience,” the raw being-in-the-world that exists before we impose narratives of productivity or meaning.

Why Wasting Time Is Revolutionary

Modernity taught us to treat attention as a resource to be optimized. But in my months of enforced idleness – unemployed, divorced, eating takeout in my childhood bedroom – I discovered what Byung-Chul Han means by “depth boredom.” Not the anxious scrolling through phones, but the fertile void where new ways of seeing emerge. Like Salgado’s photographs of miners with faces half-lost in shadow, the most revealing moments often occur outside explanatory captions.

This isn’t anti-intellectualism. It’s recognizing that rationality, when divorced from bodily presence, becomes what Nietzsche called “the will to truth turned ascetic.” The leaf exercise isn’t mindfulness – it’s un-minding. The texture reading isn’t study – it’s un-studying. Both are acts of resistance against what Han terms “the achievement-subject’s self-exploitation.”

The Gift of Unfocus

In Salgado’s “Workers” series, what lingers aren’t the documented hardships but the undocumented moments: a laborer’s calloused hand resting on a child’s shoulder, steam rising from a rice pot at dawn. These “meaningless” intervals mirror what my broken year taught me – that healing begins when we stop insisting every experience must “mean” something.

Try this tonight: read a poem upside down. Walk your usual route backward. Spend an hour with a photography book, deliberately ignoring all context. Notice how these deliberate acts of disorientation create space for what Merleau-Ponty described as “the tacit cogito” – knowledge that exists beneath language. Your fractures aren’t flaws to repair but apertures through which different light enters.

The leaf knows nothing of photosynthesis diagrams. The book feels no obligation to be profound. Why should you?

Tomorrow, miss a meeting to watch pigeons. Next Thursday, answer “What are you working on?” with “Learning how clouds dissolve.” These aren’t indulgences – they’re acts of epistemological disobedience against the tyranny of productivity. As my third reading of “The Alienist” revealed: sometimes sanity means recognizing the prison bars were of your own making.

The Madman’s Lantern: Embracing the Twilight of Clarity

The final irony of Simão Bacamarte’s story still lingers like the aftertaste of strong coffee – the most rational man in the village ultimately diagnoses himself as the true lunatic. His Casa Verde, that pristine laboratory of categorization, becomes his self-made prison. We modern seekers of clarity share his fate more than we’d care to admit. In our relentless pursuit of productivity metrics, optimized routines, and quantified self-knowledge, we’ve built our own invisible green houses – digital ones with glass walls that force us into constant performance.

The Paradox of Perfect Sanity

That afternoon when I sat on a park bench watching ice cream melt down my shirt – the first truly unproductive moment I’d allowed myself in years – something shifted. The sticky mess on my collar felt more real than any quarterly report I’d ever filed. Nietzsche’s madman with his lantern in daylight suddenly made terrible sense: our contemporary obsession with radical transparency and peak performance has become its own form of collective insanity. When every waking moment must be accounted for, measured, and optimized, we lose the capacity to simply exist.

This isn’t anti-intellectualism. The crisis isn’t rationality itself, but our cultural elevation of instrumental reason above all other ways of knowing. Bacamarte’s error mirrors our own: the belief that with enough data points, enough categories, enough analysis, we can render existence completely legible. The Casa Verde syndrome manifests today in our productivity apps that track every minute, our life-logging wearables, our compulsive sharing of curated selves.

Practical Obscurity: An Antidote

What emerges from this realization isn’t rejection of reason, but a more generous relationship with it. Here’s what that looks like in practice:

- The Unmeasured Hour: Designate sixty minutes weekly for activities that defy quantification – staring at cloud patterns, tracing wood grain with your fingertips, listening to music without multi-tasking. The key? No tracking, no journaling about it afterward.

- Purposeless Reading: Approach texts without extraction mindset. Read philosophy not to “get something” but to let the rhythm of thought wash over you. As with Salgado’s uncaptioned photographs, sometimes meaning emerges precisely when we stop demanding it.

- Intentional Inefficiency: Occasionally take the longer route home. Handwrite letters instead of emails. Bake bread without checking the clock. These small acts rebuild our tolerance for non-linear time.

The magic happens in the interstices – those unplanned moments when you miss your train and suddenly notice how the station smells of rain and old newspapers. These aren’t escapes from reality, but returns to a more textured experience of it.

Carrying the Lantern Differently

Bacamarte’s tragedy wasn’t his rationality, but his inability to doubt it. Our contemporary version involves believing that more data, more systems, more optimization will finally deliver the clarity we seek. The true breakthrough comes when we recognize that some truths only reveal themselves in peripheral vision – when we stop staring directly at the light.

This week, practice seeing sideways:

- Let one conversation unfold without steering it toward productivity

- Spend twenty minutes in a museum gazing at just one painting’s brushstrokes

- Eat a meal without documenting it

Like the alienist who finally saw his own reflection in the asylum walls, we might discover that what we’ve been calling madness was actually a forgotten way of being human. The lantern still illuminates – just not in the ways we expected.