The wooden workbench in my father’s garage held an unremarkable collection of tools – a claw hammer with its handle worn smooth from years of use, a set of wrenches hanging neatly on a pegboard, and beneath them, a long metal box coated with a fine layer of dust. I remember running my small fingers along its cool surface when I was seven, only to have my father gently redirect my attention. ‘They’re all just tools,’ he’d say, wiping grease from his hands onto his jeans, ‘but this one isn’t for children.’

The gun case sat there like any other household object in our rural Michigan home, as ordinary yet as off-limits as the electrical outlets or cleaning supplies under the sink. In the 1990s Midwest where I grew up, firearms occupied this peculiar space between the mundane and the mysterious. Neighbors would casually mention using rifles to scare off coyotes from chicken coops, while school friends showed up Monday mornings with stories of weekend hunting trips with their dads. Yet in our home, guns remained visual background noise – present but untouched, like the china set reserved for special occasions.

What strikes me now about those childhood years wasn’t the absence of guns, but rather how unremarkable their presence felt. The .22 rifle in our garage might as well have been another gardening tool or sports equipment. My father, an engineer who approached everything with practical consideration, stored it with the same care he gave to his table saw – cleaned, secured, and respected for its purpose. The cultural weight that firearms carry today simply didn’t register in our daily lives. When the local hardware store sold ammunition alongside nails and paint thinner, no one batted an eye.

This quiet coexistence shaped my earliest understanding of gun culture – not as a political stance or identity marker, but as another facet of rural practicality. The few times I heard adults discuss firearms, the conversations revolved around maintenance tips or hunting regulations rather than constitutional rights. Even at community events where men compared rifles in parking lots, the tone resembled gardeners exchanging advice about tomato varieties. The guns themselves seemed secondary to their function, like the difference between admiring a well-made shovel versus philosophizing about the concept of digging.

Only years later would I realize how profoundly that perspective would shift, both for me and for the country. The tools of my childhood were quietly transforming into symbols, their practical purposes increasingly overshadowed by ideological meanings. But on those summer afternoons in the garage, with sunlight filtering through the dusty windows and the smell of motor oil in the air, the metal box under the workbench held nothing more extraordinary than another household implement – one I wasn’t old enough to use, but whose existence required no more explanation than our lawnmower or snow shovels.

The Toolshed Perspective

In the rural America of my 1990s childhood, firearms occupied the same mental category as crescent wrenches and claw hammers – practical objects that populated tool sheds and pickup truck racks with unassuming regularity. The gun rack in our neighbor’s Ford held his deer rifle with the same matter-of-factness as the fishing rods and snow shovels wedged beside it. This was before school lockdown drills became routine, before cable news transformed firearms from implements into ideological battlegrounds.

Our family’s relationship with guns followed the pattern of many non-hunting households in the region. The single shotgun in our home lived in a locked case, its presence acknowledged but never emphasized. My father, who’d grown up on a farm, treated it with the same respectful pragmatism he applied to chainsaws or power tools – something useful that demanded caution. ‘They’re just tools,’ he’d say when I eyed the mysterious case, ‘but not tools for kids.’ The message was clear: firearms belonged to the adult world of responsibility and purpose, not childhood curiosity.

This utilitarian perspective manifested most clearly at the Johnson farm down our gravel road. Mr. Johnson’s .22 rifle served as a multipurpose problem-solver – dispatching rabid raccoons, putting down injured livestock, occasionally thinning the groundhog population threatening his garden. I remember watching through their kitchen window one summer evening as he efficiently ended a coyote’s predation on his chickens, then returned to dinner after rinsing blood from his hands at the outdoor pump. The rifle leaning against the porch wall might as well have been a hoe or an axe – another implement for managing the practical challenges of rural life.

What strikes me now about these memories is their complete lack of ideological weight. The hunting families in our community didn’t display NRA stickers or make Second Amendment declarations; the non-hunting families didn’t view guns as particular threats. Firearms simply existed within the ecosystem of rural necessities, their cultural meaning no more charged than that of a post-hole digger or a canning jar. This neutral practicality created an environment where my childhood curiosity about guns never developed into fascination or fear – they remained background objects, like the unfamiliar tools in my grandfather’s workshop that I knew had purposes I didn’t yet understand.

The Johnson farm rifle and our locked-up shotgun represented two poles of normalcy in that pre-millennium world – the constantly utilized working tool and the seldom-touched precautionary device. Neither carried symbolic weight beyond its immediate function. When Mr. Johnson handed me a spent brass cartridge to examine (the closest I ever got to handling ammunition as a child), it felt no more remarkable than being shown a particularly interesting nail or washer from his workshop. The metallic smell of the casing, the tiny firing pin dent – these were simply characteristics of an object designed for specific tasks, not relics of some greater cultural debate.

This mundane relationship with firearms began shifting as I entered adolescence. The same neighbors who’d once loaned hunting rifles as casually as lending a ladder started making cautious remarks about ‘knowing who you can trust these days.’ The local hardware store moved its gun cabinet behind the counter instead of beside the fishing gear. Yet even these changes arrived gradually, like weather patterns too large to notice until they’d already settled in. By the time I received my first shooting lesson years later, the cultural landscape had transformed in ways none of us in that 1990s tool-shed world could have anticipated.

A Lesson in the Desert

The truck tires crunched over the parched earth as we left the paved roads behind, winding through the Arizona badlands where the horizon shimmered with heat. Joshua trees stood like sentinels along our path, their twisted limbs casting jagged shadows across the rust-colored sand. This wasn’t the manicured shooting range from movies – just an unmarked stretch of desert with a natural rock formation serving as our backstop, its striated layers bearing witness to centuries of erosion.

Our instructor, a family friend named Carl, methodically unpacked his gear with the precision of a watchmaker. His hands moved through the ritual with unconscious expertise: checking the bolt action on his .30-06 Springfield, running a cleaning rod through the barrel, inspecting each brass cartridge before loading them into the magazine. The metallic clicks and snaps sounded almost musical in the desert silence. I remember how sunlight glinted off the reloading press he’d brought along – a compact device for crafting custom ammunition that spoke of countless evenings spent in his garage workshop.

‘Watch your stance,’ Carl murmured as he positioned my hands on the walnut stock. The rifle felt heavier than I’d imagined, its cold steel components fitting together with satisfying mechanical certainty. When I squeezed the trigger, three distinct sensations arrived almost simultaneously: the sharp kick against my shoulder that left a faint bruise, the deafening crack that echoed between the canyon walls, and the acrid scent of burnt gunpowder that lingered in the dry air. Downrange, a puff of dust marked where the bullet struck the sandstone cliff face.

What surprised me most was the complete absence of political context. Carl’s instructions focused entirely on practicalities: ‘Breathe out halfway before firing,’ ‘The safety’s on until you’re ready,’ ‘Always know what’s beyond your target.’ His teaching mirrored how one might explain using a circular saw or changing a tire – pure mechanics divorced from ideology. We spent the afternoon shooting at soda cans balanced on rocks, the aluminum containers dancing when hit, their punctured sides whistling in the wind.

Between rounds, we drank sun-warmed water from canteens and ate sandwiches that tasted faintly of gun oil. Carl shared stories about tracking mule deer through these same hills, describing how hunters would pack out the meat in canvas sacks during his grandfather’s era. The conversation never veered toward legislation or rights debates; just the quiet satisfaction of a skill passed between generations. As the shadows lengthened across the desert floor, we policed every spent casing – leaving the landscape exactly as we’d found it, save for a few fresh scars on ancient stone.

The Shallow Ford Becomes an Ocean

The early 2000s arrived with subtle but unmistakable changes to our family gatherings. The rifles that once leaned casually against porch railings during Thanksgiving dinners disappeared, replaced by cautious glances and carefully measured words. What had been simple tools – as unremarkable as the serving platters being passed around – gradually took on weightier meanings in our collective consciousness.

I remember the exact moment I noticed the shift. At a cousin’s wedding reception in 2003, someone made an offhand comment about the deer hunting season. Instead of the usual lively debate about prime locations or trophy bucks, an uncomfortable silence descended over the picnic table. My uncle’s prized Winchester Model 70, which had circulated freely among relatives during past hunting seasons, remained conspicuously absent from the trunk of his truck that year.

The Life of Objects

That particular rifle had lived many lives in our family. In the 1990s, it was simply “the gun we borrowed” – a shared resource like Grandma’s apple pie recipe or the canoe stored in Grandpa’s barn. Its journey between households followed practical considerations: who needed to control coyotes near their livestock, which uncle had promised to take which nephew hunting, whose property had the best sightlines for target practice.

By 2005, the same firearm had become a political Rorschach test. The passage of the Federal Assault Weapons Ban in 1994 (though it exempted hunting rifles) began quietly reshaping conversations. Post-9/11 security concerns and the 2004 presidential election turned casual gun ownership into a cultural litmus test. Where we once discussed caliber and grain, now we tiptoed around phrases like “Second Amendment rights” and “gun control.”

The Unspoken Divide

The transformation happened in increments so small we barely noticed:

- The annual family shooting competition became “that thing we used to do”

- Relatives who once swapped hunting stories started leaving the room when news coverage of mass shootings aired

- My childhood mentor, the hunter who taught me to shoot in the desert, stopped attending reunions altogether

We never had a dramatic confrontation about firearms. There were no shouting matches or ultimatums. The division revealed itself through gradual absences – fewer guns at gatherings, then fewer people, then finally fewer invitations extended across what had become, without our realizing it, a vast ideological ocean.

Objects in Mirror

Looking back through the lens of subsequent events – the Virginia Tech shooting, Sandy Hook, the growing polarization of the gun debate – those early 2000s feel almost quaint. The background noise of my childhood had become an inescapable soundtrack, the shallow ford now deep enough to drown in. The tools of my youth had transformed into symbols, their practical purposes overshadowed by everything they’d come to represent.

I sometimes wonder about that Winchester rifle. Does it still circulate among what remains of our family’s hunting enthusiasts? Does it rest unused in a safe, its owner wary of displaying it? Or has it passed into someone’s collection as a relic of simpler times? Most of all, I wonder when exactly we stopped seeing objects for what they were, and started seeing them for what they might signify.

The Tool Shed Revisited

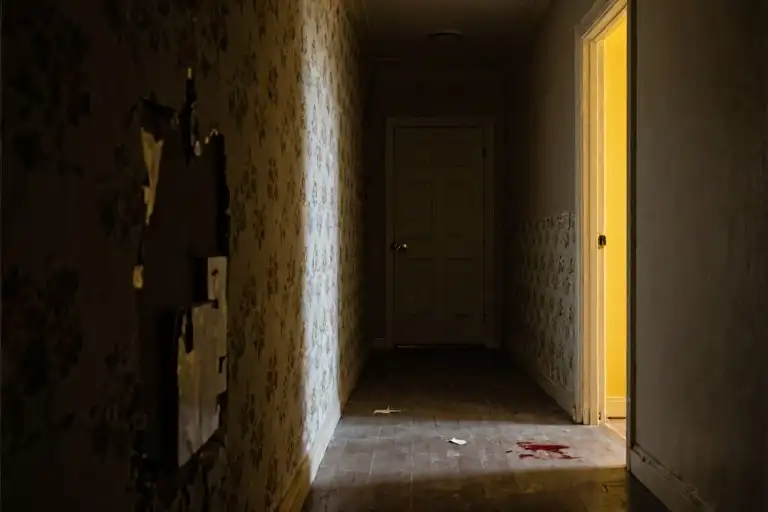

The metal latch creaks as I push open the tool shed door, releasing the familiar scent of motor oil and aged pine. Dust motes swirl in the afternoon light, settling on the same pegboard where my father’s hammer still hangs, its handle worn smooth from decades of use. Beside it, the outline of the gun case remains visible in the accumulated grime, though the box itself was donated years ago. What catches my eye now is the rusted trigger lock coiled beneath the empty space like a forgotten question.

This quiet corner of our backyard holds artifacts of two different Americas. The hammer, still used weekly to repair fence posts, represents the practical world where tools solve concrete problems. Its oiled wood gleams with continued purpose. The oxidized trigger lock tells a different story – a relic from when we last tried to reconcile the gun’s dual identity as both tool and cultural flashpoint. That summer in the desert feels lifetimes removed from today’s polarized landscape.

I run my thumb over the hammer’s familiar notches, remembering how our hunter friend would inspect his tools with similar care. His exacting ritual of cleaning the rifle barrel, testing the bolt action, and packing homemade ammunition spoke of craftsmanship rather than ideology. In that stretch of desert where the only backdrop was sun-bleached sandstone, firearms were simply instruments for teaching focus and respect. The politics came later, rising like heat mirages on the horizon until they obscured everything else.

Now when I meet childhood friends from our hunting community, we navigate conversations with the caution of hikers crossing thin ice. The same rifles that once symbolized shared outdoor traditions now serve as conversational tripwires. Somewhere along the way, the tools became Rorschach tests – what you saw in them said more about your worldview than the object itself. I often wonder if our old instructor still takes beginners to that desert spot, and if so, whether he’s had to add new warnings about more than just recoil.

On the workbench, a half-empty can of gun oil sits beside the ever-replenished tub of machine grease. Their proximity makes me consider how many everyday objects in our lives have undergone similar transformations – items whose practical functions became overshadowed by their cultural baggage. The baseball cap that stopped being just sun protection. The pickup truck that ceased to be merely a farm vehicle. These transitions happen so gradually we rarely notice until we’re already on opposite sides of the new divide.

Perhaps this is why I keep coming back to the tool shed. In this unchanged space, the hammer’s persistence as just a hammer offers quiet reassurance. Its continued simplicity suggests that some tools resist rebranding, that not every useful thing must become a symbol. The trigger lock’s rust reminds me that even our most polarized debates were once simpler conversations – before the shouting started, before we stopped listening, back when disagreement didn’t mean disconnection.

What tools in your life have taken on new meanings? I’d love to hear about the everyday objects that became something more – or less – than what they were designed to be. Your stories might help us all remember that behind every charged symbol lies a simpler origin story, waiting to be recalled.