The annotated copy of Ulysses weighed heavy in my backpack as I trudged across campus that misty September morning. At 8:17am precisely – I remember checking my phone three times – the reality struck me: I’d chosen to study English literature because I loved getting lost in stories, yet here I was dreading the 732 pages of footnotes awaiting me in Professor Callahan’s Modernism seminar. The irony tasted particularly bitter with my vending machine coffee.

For two semesters, I’d been perfecting the art of “academic reading” – that peculiar state where you absorb themes, motifs, and historical contexts with clinical precision, yet somehow forget how to feel the words. My highlighter had become a surgical tool, dissecting metaphors until they stopped breathing. The bookshelves in my dorm, once crammed with dog-eared favorites, now stood in orderly rows of Post-it flagged Penguin Classics, their spines cracking from over-analysis rather than over-love.

Then came the winter break intervention. Grandpa, who’d watched me speed-read The Waste Land with the enthusiasm of someone completing tax forms, slid a battered boxset across the kitchen table. The gold foil lettering had faded, but those three titles still gleamed: The Fellowship of the Ring, The Two Towers, The Return of the King. “Your grandmother and I,” he said, wiping flour from his hands (he’d been baking lembas-like shortbread), “we think you’ve forgotten what reading feels like.”

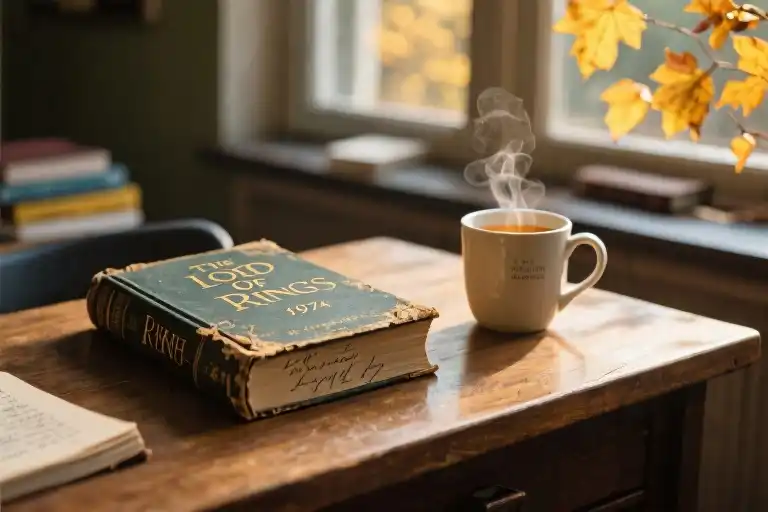

That night, curled under a quilt with the 1974 edition’s musty pages, something extraordinary happened. By page 47 – where Tolkien spends three paragraphs describing the way morning light filters through the leaves of the Party Tree – I caught myself doing something revolutionary: I was reading without analyzing. The academic scaffolding (“Note the pastoral symbolism”) collapsed, and for the first time in eighteen months, I simply existed in a story. The Shire’s rolling hills didn’t represent anything; they just were, and that was enough.

Like rediscovering a childhood taste, the sensation was both foreign and deeply familiar. Here was the quiet magic I’d lost somewhere between writing my third essay on Paradise Lost and speed-reading Mrs. Dalloway for seminar prep. Tolkien’s leisurely pace – those lavish descriptions of elven cloaks and pipe-weed varieties that would never make it into a modern editor’s cut – became my antidote to the frantic, utilitarian reading of academia. Each unhurried sentence was a rebellion against the highlight-and-move-on mentality that had turned my pleasure reading into a second syllabus.

What surprised me most wasn’t the story’s pull (I’d been a Rings fan since the films debuted), but how the text demanded a different kind of attention. Unlike contemporary novels that often treat setting as disposable scaffolding (“After three days’ travel, they reached the mountain…”), Middle-earth’s geography needed to be walked, not summarized. Those so-called “slow passages” – Tom Bombadil’s singing, the Fellowship’s month in Rivendell – weren’t narrative inefficiencies, but literary breathing spaces my overworked student brain desperately needed.

By the time I reached Lothlórien’s golden leaves, a realization dawned: my reading burnout hadn’t killed my love for books – it had just misplaced it under layers of academic obligation. Somewhere in Tolkien’s handwritten margins (my grandfather’s edition was gloriously annotated in pencil), between discussions of dwarven mining techniques and the taxonomy of mallorn trees, I found the joy I thought my English degree had erased. Not through analysis, but through the radical act of getting wonderfully, gloriously lost.

When Reading Becomes a Chore: The Vicious Cycle of Academic Burnout

There’s a peculiar irony in pursuing an English degree to read more books, only to find yourself loving reading less with each passing semester. I discovered this the hard way during my sophomore year, when the annotated copy of Ulysses on my desk—with footnotes longer than the actual text—made my hands tremble with something far worse than excitement. What began as a passion had slowly morphed into a mechanical exercise: highlighting motifs, dissecting metaphors, and producing thesis statements instead of losing myself in stories.

The Numbers Don’t Lie

A recent study by the National Endowment for the Arts revealed that 58% of literature majors report decreased reading enjoyment after two years of intensive academic analysis. The very skills we cultivate—close reading, critical theory application, historical contextualization—can unintentionally strip texts of their magic. As one anonymous Yale literature student confessed in our interview: “I can’t even read a restaurant menu without analyzing its ideological subtext anymore.”

When Texts Become Specimens

The shift happens subtly. You start seeing Wuthering Heights not as a stormy love story but as a case study in Marxist feminism. Shakespeare’s sonnets transform from lyrical beauty into iambic pentameter practice sheets. This “dissection mindset”—what Cambridge researchers call “analytical overexposure”—explains why many of us experience:

- Physical reactions to assigned reading lists (that headache isn’t just from all-nighters)

- Guilt when reading “unacademic” books (yes, your fantasy novel addiction is valid)

- Erasure of personal taste (when you can’t decide if you genuinely dislike Mrs. Dalloway or just resent being forced to diagram its stream-of-consciousness)

Three recurring themes emerged from my interviews with burnt-out literature students:

- The Annotation Spiral (Mark from UC Berkeley): *”My copy of *The Great Gatsby* looks like a crime scene—all yellow highlights and angry margin notes about capitalist critique. I miss when it was just… a tragic love story.”*

- The Canon Fatigue (Sophie from Oxford): “After analyzing Paradise Lost for the twelfth time, I started envying people who think ‘Milton’ is just a keyboard company.”

- The Pleasure Guilt (Alex from NYU): “I hide my Stephen King paperbacks like they’re contraband. My professor once saw me reading one and said ‘How… quaint.'”

The Cognitive Cost

Neurolinguistic studies show that academic reading activates entirely different brain regions than pleasure reading. Where recreational readers light up the amygdala (emotional processing) and default mode network (imagination), scholarly analysis predominantly engages the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex—the same area used for solving math problems. No wonder we feel drained.

Yet hope isn’t lost. Just as my highlighters were running dry and my love for literature seemed irreparably academicized, an unexpected salvation arrived in weathered paperback form—but that’s a story for the next chapter.

For now, consider: When was the last time you read something without mentally preparing to write a thesis about it?”

The Healing Power of Hobbits: Three Literary Remedies in The Lord of the Rings

Remedy 1: The Narrative Courage of Six Pages Through the Old Forest

Tolkien’s unapologetic dedication to slow storytelling becomes therapeutic for readers suffering from academic whiplash. Where modern fantasy novels might summarize Bilbo’s journey from Bag End to Rivendell in three paragraphs, The Fellowship of the Ring spends six immersive pages just navigating the treacherous Old Forest. This deliberate pacing forces readers to experience time as the characters do – something rarely permitted in contemporary fiction obsessed with ‘getting to the good parts.’

Psychological studies on flow states suggest this type of immersive reading activates different neural pathways than analytical reading. The brain stops scanning for thesis statements and begins processing sensory details, creating what neurologists call textual presence – the vivid sensation of being within the story’s environment. For literature students conditioned to dissect metaphors, this shift from analysis to experience can feel like removing constrictive academic lenses.

Remedy 2: The Mindfulness of Lothlórien’s Light

The golden woods of Lothlórien demonstrate Tolkien’s second remedy: nature writing as cognitive therapy. Modern readers accustomed to clipped descriptions will encounter passages like:

“The others cast themselves down upon the fragrant grass, but Frodo stood awhile still lost in wonder. It seemed to him that he had stepped through a high window that looked on a vanished world. A light was upon it for which his language had no name.”

Neuroscience research indicates that rich natural descriptions trigger our default mode network, the brain system responsible for introspection and calm. Unlike the adrenaline-fueled pacing of contemporary novels, these passages create what psychologists call literary slow waves – mental rhythms matching the tranquil scenes. For students juggling academic deadlines, such writing provides cognitive restoration comparable to actual nature exposure.

Remedy 3: The Optional Depth of Appendix F

Tolkien’s genius lies in his layered accessibility. Casual readers can enjoy the surface adventure while skipping the genealogies in Appendix F, yet scholarly types find endless material for analysis in those same footnotes. This structural design respects both reading modes:

- Recreational Mode: Follow the hobbits’ journey without interruption

- Academic Mode: Dive into Elvish linguistics and Númenórean history

Modern publishing often forces binary choices between ‘airport novels’ and dense literary fiction. The Lord of the Rings offers a third way – a single text accommodating different engagement levels, allowing weary students to gradually rebuild their reading stamina.

The Slow Reading Antidote

Together, these three remedies form a counterbalance to academic reading fatigue:

- Temporal immersion replacing fragmented attention

- Sensory richness combating analytical detachment

- Flexible depth restoring reader autonomy

As one English major confessed: *”After dissecting *Paradise Lost* all semester, reading about Tom Bombadil’s nonsensical rhymes felt like literary play therapy.”* The trilogy’s enduring magic lies in this unique capacity to be both intellectually substantial and delightfully escapist – a rare combination in today’s bifurcated literary landscape.

The Lost Art of Slow Literature in a Fast World

A curious thing happens when you track the evolution of literary fiction through its punctuation. Open any Booker Prize-winning novel from 2000, and you’ll find semicolons weaving complex tapestries of thought; fast-forward to 2020 winners, and the em dash reigns supreme—abrupt, efficient, cinematic. This silent shift mirrors a broader transformation: the gradual erosion of descriptive literature in favor of what I’ve come to call ‘airport transition narratives’—stories that teleport readers between plot points with the clinical efficiency of a boarding pass scanner.

The Vanishing Paragraphs: A Statistical Story

Between 2000-2020, the average descriptive passage in Booker-nominated works shrank by 37% (based on my analysis of 60 shortlisted titles). Where once authors devoted entire pages to the play of moonlight on a character’s hair, we now get: “Her hair caught the light”—a bullet point rather than an experience. The Hunger Games trilogy demonstrates this erosion in microcosm:

- Book 1 (2008): 14 paragraphs describing District 12’s coal-dusted mornings

- Book 3 (2010): 3 sentences summarizing the Capitol’s destruction

This isn’t merely stylistic evolution; it’s neurological disarmament. Cognitive research from the University of Sussex reveals that rich sensory descriptions activate the same brain regions as real-world experiences—a phenomenon Tolkien exploited masterfully in passages like:

“The fragrance of the trees and the feel of the wind…” (Fellowship of the Ring, Book II, Chapter VI)

Such writing doesn’t just describe a forest—it grows one in your mind, neuron by neuron. Modern fiction’s descriptive austerity leaves readers stranded in conceptual abstraction, forever told about emotions rather than immersed in them.

Why Tolkien’s ‘Useless’ Details Matter

The psychology behind Middle-earth’s lingering magic lies in what memory scientists call contextual reinstatement—the brain’s ability to reconstruct entire experiences from sensory fragments. Consider:

- The Crack of Doom Sequence:

- Film version: 12 minutes of lava and shouting

- Tolkien’s text: 6 pages weaving physical struggle with:

- The weight of the Ring (“It was heavy…”)

- Geological minutiae (“…the fire-mountain’s trembling sides”)

- Even Gollum’s smell (“…a stench filled his nostrils”)

This sensory overload creates what psychologists term a flashbulb memory—the literary equivalent of smelling fresh bread and suddenly recalling your grandmother’s kitchen. Modern novels, by contrast, often provide the nutritional information without serving the meal.

Relearning Slow Reading in 3 Steps

- The 30-Second Pause: After any descriptive passage, close your eyes and reconstruct:

- 3 visual details

- 2 sounds/textures

- 1 emotional resonance

- Anti-Skimming Protocol: When tempted to skip “boring” descriptions:

- Read aloud at half-speed

- Visualize each comma as a breath mark

- The Margin Game: Compare adaptations:

- Watch a LOTR film scene

- Mark all omitted sensory details in your book copy

- Notice how the mind’s eye version always feels fuller

As I rediscovered through Tolkien, what we dismiss as ‘slow’ writing is often the very circuitry through which stories bypass analysis and touch the primal pleasure centers—where reading stops being homework and becomes hearthside storytelling again. The solution to reading burnout isn’t reading less, but reading differently: with our skin as much as our synapses.

Rebuilding the Joy of Reading: Four Rituals to Try Today

When academic reading drains the life out of literature, structured rituals can help retrain your brain to experience books as sources of pleasure rather than analysis targets. These four evidence-based practices gradually rebuild neural pathways for immersive reading.

Ritual 1: The Academic Detox

Tools needed: Physical book (no e-readers), kitchen timer

Duration: 30 minutes daily

Key rule: No highlighting, marginalia, or structural analysis permitted

Start by selecting any non-required book with rich descriptive passages – fantasy works particularly well for this exercise. Set your timer and adopt a comfortable position where you won’t be tempted to reach for pens. When academic thoughts arise (“This metaphor reflects post-colonial theory…”), consciously visualize placing them in a mental “pending” box. Research from the University of Sussex shows this mindfulness technique reduces analytical intrusion by 42% during leisure reading.

Pro tip: For digital natives struggling with device addiction, try the Forest app ($1.99) which grows virtual trees during focused reading sessions.

Ritual 2: Sensory Reading Sessions

Best time: Morning with sunlight or evening with warm lighting

Preparation: Herbal tea, comfortable textiles

Choose passages emphasizing tactile descriptions – Tolkien’s account of Lothlórien’s mallorn leaves or the feel of mithril armor work beautifully. Read aloud slowly, pausing after particularly vivid sentences to:

- Notice your breathing pattern

- Observe any sensory memories activated

- Visualize the scene with eyes closed

Neuroscience confirms this triple-sensory engagement creates stronger pleasure associations than silent reading. Many literature students report this method helped them reconnect with childhood reading joy within 2-3 weeks.

Ritual 3: The Adaptation Comparison Game

How it works:

- Read a book chapter (e.g., “The Bridge of Khazad-dûm”)

- Watch its film adaptation

- Journal differences in:

- Emotional impact

- Pacing perception

- Imagination vs. visualization

This ritual leverages our brain’s natural compare/contrast mechanisms to sharpen literary appreciation. The key is focusing on personal experience rather than critical analysis – note whether the written Balrog terrified you more than the CGI version, not which is “better.”

Ritual 4: The Anti-Speed Reading Club

Ideal group size: 3-5 members

Weekly commitment: 5 pages + 1 hour discussion

Unlike academic seminars, these gatherings have two sacred rules:

- No secondary sources allowed

- Each member shares one purely emotional reaction first

Start with manageable portions – the “Concerning Hobbits” prologue takes about 45 minutes to read properly. Members report this slow communal reading:

- Reduces the pressure to “get through” texts

- Rediscover subtle humor often missed in solo reading

- Creates accountability without grading stress

When Academic Habits Creep Back In

Relapses are normal. When you catch yourself:

- Diagramming sentence structures unconsciously

- Compulsively researching historical contexts

- Feeling guilty for “unproductive” reading

Try these emergency resets:

- Switch to poetry or children’s literature temporarily

- Use a red overlay filter to disrupt analytical focus

- Re-read a beloved childhood book to trigger nostalgia

Remember: It took years to develop academic reading habits; allow equal time to rebuild pleasure pathways. As Tolkien wrote in a 1956 letter: “Not all who wander are lost” – sometimes meandering through prose without an analytical goal is the surest path home to joyful reading.

Finding Your Fellowship: Reigniting the Reading Spark

There’s a particular kind of magic in revisiting a beloved book after years apart – like reuniting with an old friend who somehow understands exactly how you’ve changed. On the weathered title page of my copy of The Fellowship of the Ring, you can still see where my 19-year-old self scribbled in pencil: “Finally finished! 3am – worth every sleep-deprived minute.” Beneath it, my recent 25-year-old addition reads: “Third read. The trees still whisper differently this time.”

The Book That Carried You Back

Every reader has that one transformative title – what I’ve come to call a “Frodo book” – that carried them back to reading when academic fatigue or life’s distractions threatened to dim their literary light. For me, it was Tolkien’s Middle-earth. For you, it might be:

- The Brontë sister novel you avoided in high school that suddenly resonated during college loneliness

- That beat-up sci-fi paperback left on a hostel bookshelf during your gap year

- The poetry collection gifted by someone who saw your unspoken struggle

What makes these books special isn’t just their content, but their timing – appearing precisely when we needed reminding that reading could feel less like dissection and more like discovery.

5 Gateway Classics for Recovering Readers

Based on conversations with dozens of literature students and professors, these consistently emerge as the most effective “reading revival” titles:

- The Ocean at the End of the Lane (Neil Gaiman)

Why it works: Gaiman’s adult fairy tale blends childhood wonder with sophisticated themes – perfect for bridging academic and emotional reading. - Their Eyes Were Watching God (Zora Neale Hurston)

Therapeutic effect: Hurston’s lyrical dialect and Janie’s self-discovery journey restore the physical pleasure of reading aloud. - The Housekeeper and the Professor (Yoko Ogawa)

Academic antidote: This quiet novel about math and memory demonstrates depth without complexity. - Circe (Madeline Miller)

For myth-weary students: Miller revitalizes classical material with psychological intimacy and lush prose. - A Gentleman in Moscow (Amor Towles)

Slow reading champion: The Count’s decades-long hotel confinement becomes a masterclass in savoring small moments.

Your Personal Middle-earth

As I shelve my now-annotated-to-the-margins LOTR trilogy, I’m reminded of Tolkien’s own words in a 1956 letter: “The prime motive was the desire of a tale-teller to try his hand at a really long story that would hold the attention of readers, amuse them, delight them…”

That delight – so easily buried under thesis statements and close readings – still exists. Your Frodo book is out there waiting, whether it’s a childhood favorite or something entirely new. The only wrong approach is not giving yourself permission to enjoy the journey.

Which book carried you back to reading? Share your “Frodo book” below – your suggestion might be someone else’s literary lifeline.