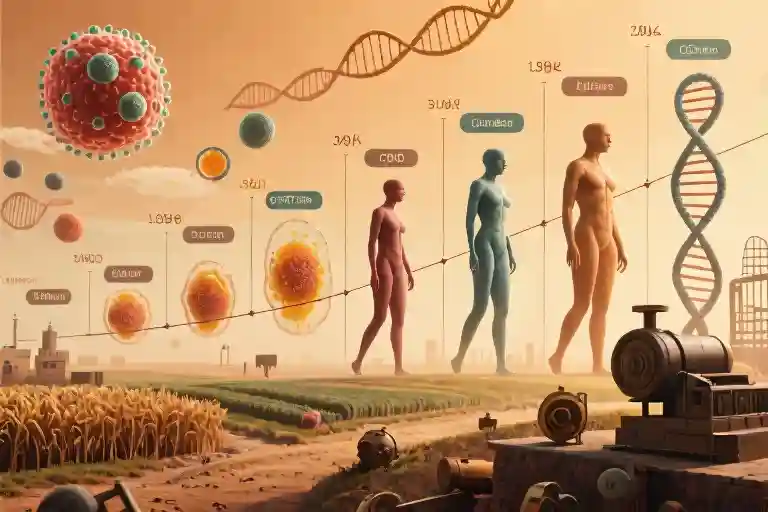

The story of gender begins with what might be history’s most awkward first date. About 1.2 billion years ago, two eukaryotic cells floated toward each other in primordial soup. One extended a cytoplasmic tendril – the biological equivalent of ‘come here often?’ – and when the reciprocation came, they exchanged genetic material in what we’d now call the world’s first hookup. This evolutionary matchmaking service had clear advantages over solitary replication (or as I like to call it, genetic masturbation), setting in motion sexual reproduction’s billion-year winning streak.

What started as a simple chromosomal swap party eventually produced the spectacular diversity of life we see today. While some organisms evolved dozens of genders (looking at you, fungi), most animals settled on a binary system. The differences between these two biological categories would shape human culture in ways those early cells could never have imagined.

Fast forward to roughly 200,000 years ago, when our Homo sapiens ancestors organized themselves into small hunter-gatherer bands. Contrary to popular assumptions about ‘caveman’ patriarchy, anthropological evidence suggests these groups maintained surprising gender equity. Men might chase antelope while women gathered tubers, but both activities contributed equally to survival. Some researchers even argue these societies practiced forms of polyamory that would make modern swingers blush.

This relative balance began tilting when humans discovered they could plant seeds instead of just finding them. The Agricultural Revolution (around 7,000 BCE) introduced two game-changing concepts: surplus and inheritance. Suddenly, physical strength became economically valuable for plowing fields and herding livestock. Pregnancy transformed from a communal asset to a productivity liability. As wealth accumulation began, men needed certainty about paternity to pass property to biological heirs. Thus was born what we might call the original patriarchy package deal: female chastity in exchange for male provisioning.

The plot thickened when early city-states emerged in Mesopotamia. Marriage became less about companionship and more about corporate merger. Elite families traded daughters like chess pieces in political strategy games. Hammurabi’s Code (circa 1750 BCE) formalized these arrangements with clauses that read like prehistoric prenups. A woman’s value became quantifiable in livestock terms – the more desirable the bride, the higher the bride price. Meanwhile, powerful men collected wives like modern CEOs collect luxury cars, with harems serving as living trophies of status.

Enter an unexpected disruptor: a radical preacher from Nazareth. When Jesus declared marriage sacred in 30 AD, he wasn’t just making theological points – he was challenging the transactional marriage market of his era. His followers would later institutionalize this view across the Roman Empire, banning polygamy and (theoretically) elevating women’s status. Of course, the Church’s marriage reforms under Charlemagne in 800 AD had less to do with women’s rights than with preventing rival nobles from building power through strategic marriages. Nothing says ‘holy matrimony’ like calculated political maneuvering.

The medieval period added new layers to our gender story. Women were paradoxically viewed as both morally frail temptresses and asexual domestic servants. Medical texts described ‘hysteria’ – a supposed female ailment cured by ‘paroxysms’ (read: orgasms) induced by physicians. The 1880 invention of the vibrator wasn’t about pleasure but workplace efficiency – doctors needed relief from repetitive stress injuries caused by treating so many ‘hysterical’ women. Meanwhile, the Church’s obsession with female purity created what historian Nancy Cott calls ‘the passionless woman’ ideal, a Victorian hangover that still lingers in modern purity culture.

Industrialization reshuffled the deck again. As factories replaced farms, the economic rationale for traditional gender roles dissolved. Women suddenly had both motive (Enlightenment ideals) and opportunity (free time from labor-saving devices) to demand equality. The 20th century then delivered three seismic shocks: world wars proving women’s workplace competence, the birth control pill separating sex from reproduction, and the internet dismantling traditional courtship rituals. Each innovation chipped away at the biological determinism that had constrained gender roles for millennia.

Which brings us to today’s paradoxical moment. By nearly every metric – workplace participation, education attainment, domestic violence rates – gender equality has never been higher. Yet cultural anxiety about changing roles has never been louder. This tension isn’t new; every generation believes the next is morally bankrupt. Ancient Greeks fretted about ‘soft’ boys raised on poetry instead of warfare. Medieval clergy warned that women reading novels would destroy society. 1950s critics claimed working mothers created juvenile delinquents. The current panic about dating apps and gender fluidity is just the latest installment in humanity’s longest-running soap opera.

What often gets lost in these debates is how profoundly our environment shapes gender expression. The same species that produced Victorian prudes also created the free love movement. Biology may deal the cards, but culture plays the hand. As we stand on the brink of AI companions and genetic engineering, one wonders what future historians will say about our own transitional moment. Perhaps they’ll note how we finally stopped asking whether men and women are fundamentally different, and started asking a better question: different at what, and why does it matter?

When Eukaryotes Started Dating

Long before Tinder bios and awkward first dates, the earliest courtship rituals were playing out at the microscopic level. Around 1.2 billion years ago, two eukaryotic cells would engage in what we might generously call the world’s first flirtation—membrane tickling followed by chromosomal mingling. This wasn’t just cellular small talk; it was an evolutionary breakthrough that would shape all complex life.

Sexual reproduction emerged as nature’s upgrade from what we might term “genetic masturbation”—the lonely process of asexual replication. By swapping DNA like mix tapes, organisms gained a survival edge: genetic diversity. This biological innovation became so successful that today, nearly every multicellular organism engages in some form of sex. While some plants and fungi evolved multiple genders, animals largely settled on a binary system—not because it was ideal, but because it was good enough to keep the party going.

The transition from solitary division to partnered reproduction brought unexpected consequences. Early mammals developed emotional capacities alongside their physical adaptations. About 125 million years ago, proto-mammals began exhibiting attachment behaviors—the neurological groundwork for what we now call love, anger, and sadness. These weren’t conscious emotions as we understand them, but biological programs that enhanced survival. A mother protecting her young needed hormonal reinforcements; mates forming temporary bonds required chemical rewards.

Then came the cosmic reset button. The asteroid impact 66 million years ago that wiped out dinosaurs suddenly made the world safer for small, furry creatures. With giant reptilian predators gone, mammals could afford to invest energy in complex social behaviors rather than constant survival mode. This set the stage for primates to emerge 55 million years later, carrying forward both the biological machinery and emotional software of their ancestors.

What makes humans particularly interesting is our mild sexual dimorphism compared to other great apes. Gorillas evolved extreme size differences between sexes—silverback males can weigh twice as much as females—reflecting their harem-based social structure. Chimpanzees and humans show more moderate differences, suggesting evolutionary paths where female choice played greater roles. Our 15-20% size disparity hints at a history where neither brute strength nor pure cunning dominated, but some messy combination of both.

This biological legacy manifests in subtle but measurable ways. Male humans tend toward greater physical aggression and spatial reasoning, while females generally excel in verbal fluency and social cognition. These aren’t absolute rules but statistical tendencies—overlapping bell curves rather than binary categories. More importantly, they represent starting points that culture can amplify, mitigate, or redirect entirely. The same evolutionary pressures that gave us these tendencies also gave us neuroplasticity—the ability to rewire ourselves through experience.

As we’ll see, these biological foundations would interact with cultural innovations in surprising ways. The invention of agriculture, the rise of cities, and later technological revolutions didn’t erase our evolutionary heritage, but they did create new rules for the ancient game of survival and reproduction. What began as membrane tickles between single-celled organisms would eventually lead to marriage contracts, dating apps, and the occasional awkward conversation about “where this is going.”

The Naked Ape’s Quirks (2 Million – 10,000 Years Ago)

Our story takes a sharp turn when early humans started walking upright. That simple anatomical change did more than free our hands – it reshaped our entire mating game. Compared to other primates, humans developed remarkably mild sexual dimorphism. A male gorilla weighs nearly twice as much as his female counterpart, while human males average only 15-20% more mass than females. This biological clue suggests something profound about our species’ social evolution.

Primatologists observe a clear pattern: species with extreme size differences between sexes (like gorillas) tend toward polygamous systems where dominant males control harems. Those with minimal dimorphism (like gibbons) usually form monogamous pairs. We humans landed somewhere in between – physically similar enough to hint at cooperative tendencies, but with just enough difference to maintain some fascinating behavioral variations.

The Hunter-Gatherer Equalizer

Anthropological evidence from contemporary hunter-gatherer societies paints a surprising picture of prehistoric gender dynamics. While men typically pursued game, women provided 60-80% of the group’s calories through gathering. This economic interdependence created what some researchers call “reverse dominance hierarchies” – systems where no single gender could monopolize power. Fossil records show prehistoric women had robust arm bones comparable to modern female athletes, suggesting active participation in foraging and tool use.

The !Kung people of southern Africa offer a living window into this ancient balance. Women move freely between camps, initiate marriages, and maintain economic autonomy through their gathering expertise. Men’s hunting success actually depends on women’s knowledge of plant cycles and water sources. It’s a far cry from the “caveman dragging woman by hair” trope popularized by mid-century cartoons.

The Brain Difference That Might Not Matter

Modern neuroscience reveals subtle variations in male and female brain structure. Men tend to have more volume in the amygdala (associated with aggression), while women show greater development in the prefrontal cortex (linked to emotional regulation). But here’s the twist – these differences shrink dramatically in societies with greater gender equality. Norwegian studies found that as educational and occupational opportunities equalized, cognitive differences between sexes diminished by over 60%.

This plasticity suggests our famous “Mars vs. Venus” mentalities may be less about hardwiring and more about thousands of generations fine-tuning different survival skills. When your life depends on tracking antelope herds or remembering which berries won’t kill your children, natural selection gets very specific about which traits to emphasize.

The Walking Contradiction

Human sexuality became biology’s greatest paradox during this period. We developed concealed ovulation (unlike chimpanzees’ obvious swelling), allowing for continuous sexual receptivity. Combine this with our moderate dimorphism, and you get a species biologically primed for both pair bonding and strategic promiscuity. Anthropologist Helen Fisher calls it “serial social monogamy with clandestine adultery” – a mouthful that explains everything from Victorian scandals to modern dating apps.

Our ancestors left us with this peculiar legacy: bodies suggesting cooperation, brains capable of deception, and social structures constantly oscillating between equality and hierarchy. The next chapters of human history would see this tension play out in increasingly complex ways, but the roots of our modern gender dynamics were already firmly planted in the African savanna.

When Wheat Changed the Game: Agriculture’s Gender Revolution (7000BC-500BC)

For 200,000 years, our hunter-gatherer ancestors maintained a relatively balanced division of labor. Men tracked game while women gathered plants – both skills equally vital for survival. Anthropological evidence suggests these small bands operated with surprising gender equity. Then someone noticed a wild wheat stalk growing particularly plump seeds…

The Neolithic Revolution didn’t just domesticate plants and animals – it domesticated human relationships. Suddenly, productivity shifted from mobility to stability. Heavy plows replaced lightweight digging sticks. Large draft animals became agricultural assets. In this new equation, male physical strength gained disproportionate economic value.

Three seismic changes occurred almost simultaneously:

- The Pregnancy Penalty: Farming required continuous labor through planting and harvest seasons – impossible for women during late pregnancy and infant care. Each child now carried an opportunity cost measured in bushels of wheat.

- Property Paradox: Surplus grain created the first inheritable wealth. Men demanded paternity certainty to pass land to biological heirs, transforming female sexuality into a commodity.

- Muscle Premium: Clearing fields and managing livestock favored upper-body strength. A study of ancient plow designs shows they required 30% more pulling force than women’s average capacity.

The earliest legal codes reveal this shift. Hammurabi’s laws (1750BC) prescribed:

- Bride prices paid to fathers (Article 159)

- Death for adulterous wives but not husbands (Article 129)

- Inheritance exclusively through male lineage (Article 170)

City-states institutionalized these norms. Sumerian temple records show priestesses gradually excluded from economic roles they’d held for millennia. Egyptian art begins depicting women smaller than men – a symbolic shrinking that would persist through Renaissance paintings.

Yet the agricultural revolution wasn’t uniformly oppressive. In Mesopotamia’s early city-states, some women retained economic power as tavern keepers and textile merchants. The Epic of Gilgamesh (2100BC) features Shamhat, a temple priestess whose sexual initiation of Enkidu suggests sacred prostitution carried status.

The real tragedy unfolded gradually. As plow agriculture spread, societies developed what economists call “plow bias” – cultural norms that persist long after their economic rationale disappears. Modern MRI studies show societies descended from plow cultures still exhibit stronger implicit gender stereotypes, even in post-industrial settings.

What’s often missed in this narrative is the male sacrifice. Agricultural societies demanded men become expendable production units. Skeletal remains show farmers developed arthritis decades earlier than hunter-gatherers. The same systems that privileged male authority also bound men to lifelong drudgery – a tradeoff we’re still unraveling today.

Next time you pass a wheat field, consider how those golden stalks quietly reshaped human intimacy for fifty centuries. The tractor may have replaced the ox-drawn plow, but some furrows run deeper than machinery can reach.

When Marriage Became Big Business (30AD-1600AD)

The story of how marriage went from a practical arrangement to a sacred institution is stranger than most fairy tales. It begins with an obscure Jewish preacher who had some radical ideas about treating women decently, and ends with medieval doctors inventing the world’s first mechanical sex toy. Along the way, we’ll see how the Catholic Church turned marriage into a political weapon, and how society managed to simultaneously demonize female sexuality while creating an entire medical specialty devoted to giving women orgasms.

Jesus and the Marriage Makeover

Around 30 AD, a carpenter’s son started preaching that women shouldn’t be treated like property. This was, to put it mildly, not how things worked in the ancient world. The Roman Empire at the time had all sorts of creative marital arrangements – emperors maintained harems, wealthy men traded wives like baseball cards, and divorce was basically as common as changing your Facebook status today.

Then Jesus showed up declaring that marriage should be permanent and sacred. Historians still debate whether he meant this literally or metaphorically, but one thing’s clear: this was the first time anyone in power suggested that women might deserve equal dignity in relationships. Of course, the establishment responded by nailing him to a cross – an early example of how threatening gender norms can be to those in power.

How the Church Invented ‘Til Death Do Us Part

Fast forward to 800 AD. Europe’s in chaos after the Roman Empire collapsed, and the Catholic Church emerges as the only stable institution. Pope Leo III and Charlemagne faced a problem: dozens of warring kingdoms kept trying to consolidate power through strategic marriages. One king might marry five women from different regions to build alliances, then divorce them when convenient.

Their brilliant solution? Declare marriage a sacred, permanent union between one man and one woman. No divorces. No remarriages. No illegitimate heirs. Suddenly, kings couldn’t use marriage as a political chess move anymore. What seemed like moral reform was actually a brilliant power play – by controlling marriage, the Church controlled the succession of every throne in Europe.

This created the template for modern marriage: emotional, permanent, and supposedly sacred. Never mind that most peasants still treated it as a practical arrangement – the ideal was set. We’re still living with the consequences today every time someone complains about the decline of “traditional marriage.”

The Medieval Female Sexuality Paradox

Here’s where things get weird. Medieval Europe developed a bizarre double standard about women’s sexuality. On one hand, the Church taught that women were dangerously sexual temptresses who needed to be controlled. On the other hand, doctors were diagnosing half the female population with “hysteria” – a supposed illness caused by sexual frustration.

The treatment? Manual stimulation to “paroxysm” (they couldn’t even say orgasm). Wealthy women would visit doctors weekly for these “treatments.” By the 1880s, doctors were complaining of hand cramps from all the manual labor – leading Joseph Granville to invent the electromechanical vibrator in 1880. That’s right: the vibrator was originally medical equipment, making it one of the few inventions created specifically to make women’s lives better.

What’s fascinating is how this reflects society’s conflicted views. Female sexuality was simultaneously feared and pathologized, yet also medically validated in a way that would shock the Victorians. It’s a perfect example of how even in repressive times, human nature finds ways to assert itself.

The Takeaway

This period shows how marriage has always been about power as much as love. The “traditional marriage” we hear so much about was actually a radical innovation when the Church invented it – and like most innovations, it was designed to solve someone’s problem (in this case, keeping kings from getting too powerful). Meanwhile, the vibrator’s origins remind us that even in restrictive societies, women’s needs have a way of making themselves known – often in the most unexpected ways.

Next time someone talks about “getting back to traditional values,” you might ask which tradition they mean – the one where kings had harems, or the one where doctors gave vibrator prescriptions? History’s funny that way.

When Steam Met Aprons: The Industrial Revolution’s Gender Revolution

The clatter of looms in Manchester cotton mills did more than transform wool into fabric—it fundamentally rewrote the script of human relationships. As factories mushroomed across 19th century Europe, a peculiar domestic experiment unfolded: for the first time in 7,000 years of agricultural civilization, significant numbers of men could support entire families through wage labor alone. This economic novelty birthed the “male breadwinner” model, complete with its accompanying mythology of separate spheres—men conquering the public world while women guarded the sanctity of the home.

The Economics of Domesticity

Three converging forces created this historical anomaly:

- Mechanized Production: Steam-powered factories concentrated economic value creation outside households

- Urbanization: Detached nuclear families replaced multigenerational farming units

- Child Labor Laws: Removing children from workforce increased domestic supervision needs

Victorian moralists like Sarah Stickney Ellis framed this arrangement as natural law, her 1839 manual The Women of England declaring: “The home is woman’s proper sphere, and in this sphere, she may be a queen.” The irony? This “timeless tradition” lasted barely 150 years before industrialization’s next phase dismantled it.

War Machines and Workplace Revolutions

The two World Wars exposed the fragility of prescribed gender roles. When 16 million American men deployed during WWII, propaganda posters like “Rosie the Riveter” recast factory work as patriotic duty for women. The results shocked traditionalists:

- US female workforce participation jumped from 27% (1940) to 37% (1945)

- 350,000 women served in military auxiliary corps

- Munitions plants reported female workers outperforming men in precision tasks

Postwar attempts to restore prewar norms faltered. Though 1945 ads urged women to “give back” jobs to returning soldiers, surveys showed 80% of female war workers wished to remain employed. The genie of economic autonomy refused to return to its domestic bottle.

The Unintended Consequences

This era’s legacy manifests in modern paradoxes:

- The Wages of Domesticity: The “housewife” ideal created middle-class leisure that enabled first-wave feminism

- Temporary Becomes Permanent: Women’s wartime workforce entry established precedents for equal pay lawsuits

- Education Spillover: Factory earnings allowed daughters to access higher education, fueling second-wave feminism

As historian Stephanie Coontz observes: “The industrial family model was like a bridge—it collapsed under the weight of the very prosperity it helped create.” The factories that initially confined women to domesticity ultimately became their vehicle for liberation.

The Pill and the Revolution (1960AD-1990AD)

In 1960, a small plastic case containing 21 white tablets hit pharmacy shelves, looking about as revolutionary as a pack of breath mints. Yet this unassuming object – the birth control pill – would trigger more social change than any political manifesto or protest march of the 20th century. For the first time in human history, women could reliably separate sex from reproduction with something more convenient than a calendar and crossed fingers.

The biological implications were straightforward: female fertility became opt-in rather than opt-out. But the sociological aftershocks rippled outward in unpredictable ways. Within five years of the pill’s approval, the percentage of female college students jumped from 35% to 43%. By 1982, women would outnumber men on campuses entirely. This wasn’t coincidence – it was causation. The average age of first marriage, static for centuries, suddenly began climbing as women invested in education before families.

Legislative changes followed this demographic shift. The 1964 Civil Rights Act in the US (Title VII) and similar laws abroad made workplace discrimination illegal, but enforcement required women who could delay childbearing to establish careers. The pill created that critical mass. By 1970, the number of women in medical schools doubled; by 1980, tripled. Contraception quietly enabled feminism’s second wave not through ideology but through practical autonomy – the freedom to plan lives in years rather than menstrual cycles.

This new control came with cultural whiplash. Ancient social scripts collided with modern possibilities. In 1967, a Gallup poll found 57% of Americans believed birth control pills should be banned for unmarried women. The same year, 500,000 young people gathered at San Francisco’s Human Be-In, many high on both psychedelics and the novel idea that sex could be recreational rather than transactional. The generational divide became literal: the average age of first intercourse dropped from 19 to 16 within a decade, while the average age of first marriage rose from 20 to 24.

Economic data reveals the quiet revolution. Between 1960-1980:

- Women’s wages grew 6x faster than in previous decades

- The gender pay gap narrowed by 15 percentage points

- Female-led households below poverty line decreased by 30%

Yet the pill’s impacts weren’t uniformly liberating. Some women reported feeling pressured into sexual availability without reproductive excuses. The 1970s saw both soaring divorce rates and an unexpected phenomenon: loneliness epidemics among single career women. Biology and culture were evolving at different speeds – our bodies adapted to new freedoms faster than our emotional templates could adjust.

By the 1980s, the consequences grew more complex still. HIV/AIDS brutally reintroduced sexual risk calculus just as women gained hard-won autonomy. The vibrator, once a medical device for treating “hysteria,” became a $1 billion retail industry as women explored pleasure beyond partnership. And in 1982, when women officially became the majority of college graduates, no one noticed the quietest revolution of all: for the first time, educated women could selectively reproduce with educated men, accelerating cognitive stratification.

Looking back, we often frame this era through protests and bra-burning. But the deeper story is pharmacological – how a tiny dose of synthetic hormones changed not just who controls reproduction, but how societies structure time, education, and ambition itself. The pill didn’t just give women choices; it redesigned the entire architecture of human capital. And we’re still deciphering the blueprints.

When Algorithms Met Love: The Digital Reshaping of Intimacy (1993-2014)

The internet arrived in our living rooms carrying two revolutionary gifts: instant access to information, and an entirely new way to trip over our own awkwardness when asking someone out. What began as clunky dial-up connections and pixelated chat rooms quietly dismantled courtship rituals that had survived since the Victorian era. By 2014, we found ourselves swiping right on potential partners while simultaneously lamenting the death of romance—a paradox as old as technological progress itself.

The Great Disintermediation

Traditional dating had always relied on intermediaries—matchmakers, church communities, even the local bartender who’d nudge two patrons toward each other. The internet vaporized these gatekeepers overnight. Early platforms like Match.com (1995) and eHarmony (2000) promised scientific compatibility matching, though their algorithms were about as sophisticated as a middle-school love note. Still, they normalized the radical idea that you could evaluate a life partner through screen-mediated interactions before ever smelling their actual pheromones.

Then came the second wave. Facebook (2004) turned relationship status into public performance art, while smartphones equipped with GPS birthed location-based apps like Grindr (2009) and Tinder (2012). Suddenly, proximity mattered more than compatibility algorithms. A 2013 study found the average courtship period before first physical contact shrank from six weeks to six minutes—roughly the time it takes to walk from a coffee shop to someone’s apartment after matching.

The Paradox of Plenty

Behavioral economists call it the “tyranny of choice”—when presented with infinite options, humans freeze like deer in headlights. Dating apps perfected this phenomenon. A 2014 Journal of Personality and Social Psychology study revealed something counterintuitive: people shown 50 potential partners made worse choices than those shown only 5. Our Stone Age brains, evolved to evaluate mates in small hunter-gatherer bands, short-circuited when confronted with endless profiles. Many users reported feeling lonelier after swiping through hundreds of matches than they had before downloading the apps.

Yet the data told a different story. Between 1993-2013, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control recorded a 30% drop in sexually transmitted infections among teens. The National Crime Victimization Survey showed rape rates plummeting 85% since 1980—a decline steeper than the drop in overall violent crime. Somehow, amid all the hand-wringing about hookup culture destroying morality, young people were having safer sex and experiencing less sexual violence than any generation in recorded history.

The New Intimacy Architects

Silicon Valley’s engineers became accidental relationship therapists. Tinder’s co-founder Sean Rad admitted they initially designed the swipe mechanism for efficiency, never anticipating how it would train users to make snap judgments about human worth. The app’s interface—judging people like catalog items—proved so addictive that by 2014, users collectively swiped 1.6 billion times daily. Psychologists began noticing a phenomenon they called “dating app burnout,” where prolonged exposure to these mechanics eroded users’ capacity for real-world attraction.

Meanwhile, another quiet revolution unfolded in plain sight: the normalization of niche desires. Platforms like OkCupid allowed users to filter for everything from political leanings to Dungeons & Dragons preferences. For marginalized groups—LGBTQ+ individuals, polyamorous communities, people with rare kinks—this meant finding partners without risking physical safety. A 2013 study in the Journal of Social and Personal Relationships found that couples who met online reported slightly higher marital satisfaction than those who met offline—possibly because they could pre-screen for dealbreakers.

The Backlash That Never Came

Every technological shift in human mating habits has triggered moral panic—from the Catholic Church fretting about love marriages to 1950s parents fearing rock ‘n’ roll would corrupt their daughters. The digital dating revolution proved uniquely resilient to backlash. Even as newspapers ran headlines about “the end of romance, three converging trends made criticism ring hollow:

- The Data Defense: Hard statistics showed digital natives were having safer, more consensual sex than previous generations

- The Convenience Factor: Busy urban professionals—especially women—embraced apps that eliminated bar-hopping and awkward blind dates

- The Nostalgia Trap: Older critics who lamented “the good old days” conveniently forgot that those days included rampant workplace harassment and marital rape exemptions

By 2014, the debate had subtly shifted. The question wasn’t whether algorithms should mediate relationships, but how to design them more ethically. Early warning signs emerged about mental health impacts—a 2014 University of Michigan study linked Facebook usage to decreased life satisfaction—yet few wanted to return to a world where your dating pool was limited to your zip code and social circle. Like agriculture and industrialization before it, the digital mating revolution proved irreversible. The genie wasn’t going back in the bottle—even if that genie now lived in the cloud and required a monthly subscription fee.

The Never-Ending Cycle of Gender Panic

History has a peculiar way of repeating itself, especially when it comes to fretting about gender roles. That collective gasp you hear every time society evolves? It’s the same sound our ancestors made when women started wearing pants or men grew their hair long. The script stays remarkably consistent: new technology or social change emerges → gender norms get disrupted → older generations clutch their pearls → eventually everyone adjusts… just in time for the next upheaval.

Consider this pattern:

- 4th Century BC: Aristotle complains that Spartan women have too much freedom

- 1690s: Puritan pamphlets warn that coffeehouses are making English men effeminate

- 1920s: Newspapers declare flappers are destroying civilization with their knee-showing, cigarette-smoking ways

- 2020s: Podcasters debate whether TikTok is turning boys into soy-faced beta males

The ingredients never change: take one part technological progress (agriculture, birth control, social media), mix with shifting economic realities, sprinkle in youthful rebellion, and voilà—you’ve got a fresh batch of moral panic simmering. What varies is only the seasoning: sometimes it’s framed as “protecting women’s virtue,” other times as “preserving masculine vigor.”

Yet beneath this predictable chaos, the data reveals surprising progress:

- Gender violence rates have plummeted (down 85% for rape since 1980)

- Educational parity has flipped (women now earn 60% of master’s degrees)

- Household dynamics have transformed (millennial fathers spend 3x more time with kids than 1960s dads)

These improvements didn’t happen despite the periodic panics, but arguably because of them. Each generational freak-out forces society to renegotiate its gender contract. The Victorian terror about women reading novels? Paved the way for female literacy. The 1950s hysteria over working wives? Made dual-income households normal.

So what’s next in this endless dance? If history holds true, our current debates about AI relationships and gender fluidity will seem quaint in 50 years. The real question isn’t whether change will come—it’s which emerging technology will trigger the next great gender quake. Genetic engineering? Brain-computer interfaces? Or perhaps something we haven’t even imagined yet.

One thing’s certain: somewhere, a group of elderly culture warriors is already drafting their complaint about it.