The faint smell of cheap flashlight plastic still lingers in my memory, mixed with the musty scent of well-thumbed paperback pages. There was a particular thrill in reading Dragonlance Chronicles under blankets at 2 AM, terrified my parents would catch me awake yet unable to stop turning pages. By 1995, I’d logged 62 novels—mostly fantasy and sci-fi with cracked spines and neon-highlighted passages. Fast forward to 2015, and that number dwindled to 3 lonely titles collecting dust on my nightstand.

What happened to the girl who used to annotate paperback margins with theories about magical systems and character motives? The transformation wasn’t sudden. Like many readers who grew up before smartphones dominated our attention spans, my relationship with fiction underwent quiet revolutions—some conscious, others as subtle as seasons changing.

This isn’t just nostalgia. Pew Research shows 27% of adults who regularly read fiction in their teens abandon it by their 30s. The reasons vary: college syllabi prioritizing academic texts, careers demanding practical reading, or simply that mysterious moment when scrolling through social media feels easier than committing to a 500-page journey. For me, it was all three—plus something harder to define. Somewhere between graduate school’s required readings and adulthood’s endless to-do lists, I forgot how to play in imaginary worlds.

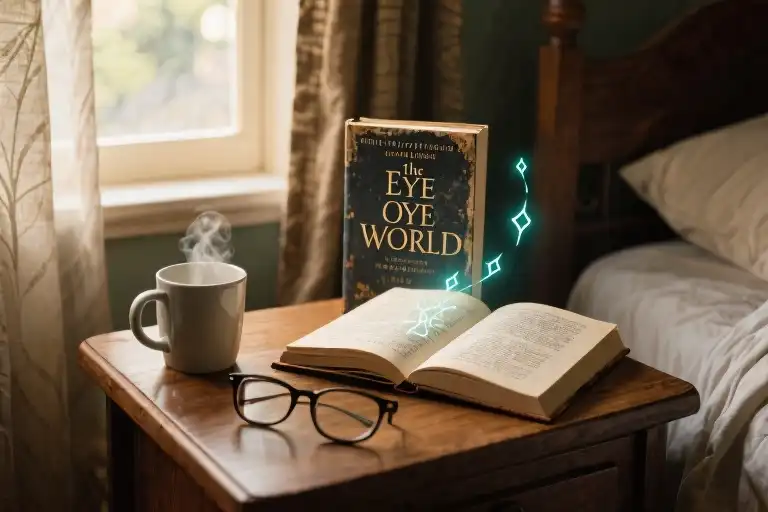

Yet here’s the curious twist: when I recently reopened The Eye of the World, Robert Jordan’s prose didn’t feel dated—I did. The same words that once swept me into heroic battles now revealed intricate social hierarchies. The Aes Sedai’s White Tower? Suddenly less about magic and more about institutional power dynamics. Trollocs weren’t just monsters but embodied fears of the ‘other’ in ways my teenage self never considered.

Books don’t change. Readers do. And that’s the magic of returning to old favorites with new eyes—you’re not just rediscovering stories, but measuring your own growth. Whether it’s through the lens of sociology, psychology, or simply lived experience, every rereading is a conversation between who you were and who you’ve become.

The Lifecycle of a Reader

The Paperback Renaissance (1990-2000)

My childhood bedroom shelves bowed under the weight of mass-market paperbacks, their spines cracked from repeated readings. This was the golden age of pre-internet immersion, when fantasy worlds weren’t streams to dip into but oceans to drown in for weeks at a time. I’d trace maps of imaginary kingdoms with my finger, memorize fictional genealogies like they were family histories, and develop strong opinions about magic systems as if they were political ideologies.

The tactile experience defined this era – the chemical smell of fresh ink on cheap paper, the satisfying crinkle of a new book’s spine being broken, the way certain publishers used matte covers that felt like suede (Piers Anthony’s Xanth novels always had this texture). My copy of Terry Brooks’ The Sword of Shannara still bears neon highlighter streaks where teenage me marked passages about the Druid Allanon’s wisdom – though now I wonder if I was unconsciously drawn to his role as a gatekeeper of esoteric knowledge.

The Last Hurrah (2005-2010)

By my mid-twenties, reading had become less about quantity and more about sustained intensity. Susanna Clarke’s Jonathan Strange & Mr Norrell arrived like a thunderclap in 2005 – an 800-page doorstopper I consumed in three marathon sessions, forgetting meals and sleep. Where childhood reading was wide and shallow, this period became narrow and deep. Tad Williams’ Otherland series particularly resonated, its virtual worlds foreshadowing our emerging digital realities. The worn corners of my War of the Flowers copy still testify to how often I revisited its themes of artistic creation and immortality.

What made these books different from childhood favorites was their willingness to sit with ambiguity. Where Piers Anthony’s novels had clear moral binaries, these works thrived in gray areas – much like adulthood itself. The shift from paperback to hardcover during this period felt symbolic: these weren’t disposable adventures but permanent fixtures in my mental landscape.

The Great Drought

The transition happened so gradually I didn’t notice the water was gone until I found myself in a desert. Sometime after 2010, my bookshelves began filling with nonfiction – academic journals, policy reports, histories of economic thought. What began as graduate school necessities became unconscious preferences. Where I once measured reading in stories absorbed, I now counted insights per chapter.

Several factors conspired to create this fiction famine:

- The Attention Economy Shift: Smartphones turned reading into a series of interruptions rather than sustained immersions. A 300-page novel required focus my Twitter-addled brain struggled to muster.

- Professionalization of Thought: Academic training rewired my brain to privilege argument over narrative, evidence over emotion. Fiction began feeling “unproductive.”

- The Reality Hunger: As global crises multiplied, escaping into imaginary worlds started feeling irresponsible when there was so much real-world complexity to understand.

The irony? My social science readings kept referencing novels as cultural artifacts. Economists cited Dickens on inequality, political theorists analyzed Orwell’s surveillance visions, sociologists used Le Guin to explain gender constructs. The tools I’d gained for analyzing society were equally applicable to the fiction I’d abandoned – I just hadn’t realized it yet.

Diagnosing the Fiction Famine

The moment I traded my dog-eared copy of The Dragonbone Chair for a stack of sociology textbooks marked the beginning of what I now call my “fiction famine”—that inexplicable decade when novels disappeared from my nightstand. At first, I told myself it was just temporary. College demanded rigorous reading, after all. Those color-coded highlighters weren’t going to wield themselves across Foucault and Weber. But when graduation came and went, and my bookshelves remained dominated by nonfiction, I had to confront the uncomfortable truth: somewhere along the way, I’d unlearned how to read for wonder.

The Surface Culprits

Like many readers who experience this shift, I initially blamed practical circumstances:

- Academic Overload: My literature major required analyzing texts like a pathologist dissecting specimens—every metaphor scrutinized, every theme catalogued. The analytical lens that enriched my studies somehow made recreational reading feel like unpaid homework.

- Adulting Fatigue: Between grad school applications and rent payments, curling up with a 900-page fantasy epic started feeling as feasible as building a treehouse. The mental bandwidth required for fictional worlds had been reallocated to spreadsheets and cover letters.

Yet these explanations only scratched the surface. When I polled fellow former fiction lovers, a pattern emerged: our reading droughts often coincided with smartphone ownership. The same devices that delivered endless information also rewired our attention spans. Where we once devoured chapters during subway rides, we now scrolled through tweets between stops. Neuroscientist Maryanne Wolf’s research on “skimming culture” suggests this isn’t just anecdotal—digital reading promotes “efficiency” over immersion, making sustained engagement with novels increasingly difficult.

The Deeper Currents

Beneath these practical shifts flowed subtler cultural undercurrents:

- From Escape to Engagement

In my twenties, as student loans and climate anxiety took root, stories about chosen ones saving the world began feeling less like adventures and more like fairy tales. I craved narratives that helped me understand systemic problems rather than imagine their magical solutions. This mirrored a broader trend: Pew Research Center data shows nonfiction readership grows steadily after age 30, particularly for books about politics and social issues. - The Rise of the “Useful” Read

Productivity culture transformed reading into another self-optimization tool. Why “waste time” on imaginary kingdoms when you could study Atomic Habits? This transactional mindset—amplified by social media’s highlight reels of people reading “100 books a year!”—turned pleasure reading into a guilty indulgence. - The Paradox of Choice

With infinite entertainment options, committing to a novel began feeling like ordering the same entrée every night at a buffet. Streaming services and video games offered immediate gratification without the cognitive investment novels demand. As author Naomi Baron found in her global reading study, many now associate print books with “slow food” in a fast-food world.

The Turning Point

What finally reignited my fiction hunger wasn’t nostalgia, but an unexpected crossover between my professional and personal worlds. While researching narrative psychology, I stumbled upon studies showing how novels enhance empathy and critical thinking—skills my nonfiction-heavy diet had left undernourished. More intriguingly, researchers like University of Toronto’s Keith Oatley demonstrated that literary fiction readers develop sharper social perception than nonfiction readers. Suddenly, my abandoned fantasy collection didn’t seem like escapism, but a neglected training ground for understanding human systems.

This revelation led me back to The Eye of the World with fresh eyes. Where I’d once seen only Trollocs and Aes Sedai, I now noticed Robert Jordan’s intricate commentary on power structures—how the White Tower’s hierarchy mirrored real-world institutions, or how the Aiel’s clan systems reflected anthropological studies of nomadic cultures. The story hadn’t changed, but my ability to read it had deepened in ways only nonfiction once could.

Perhaps our fiction famines aren’t abandonments, but necessary fallow periods. Like fields left unplanted to regain nutrients, sometimes we need seasons away from imagined worlds to bring richer harvests of meaning when we return. The books wait patiently, knowing we’ll meet them again as different people—and that’s when the real magic begins.

The Wheel of Time Turns Differently

Returning to Robert Jordan’s The Eye of the World after fifteen years felt like discovering a palimpsest—the original adventure story still visible, but layered with meanings my teenage self never perceived. Where I once followed Rand al’Thor’s hero journey with breathless excitement, I now find myself reverse-engineering the White Tower’s power structures. The book hasn’t changed, but the lens through which I read certainly has.

Hero’s Journey or Bureaucratic Manual?

At fourteen, I meticulously tracked the progression of Rand’s sword skills and channeling abilities. Today, the Aes Sedai’s organizational chart fascinates me more than any magical battle. The White Tower operates with the calculated precision of a medieval church-state hybrid:

- Meritocracy facade: Novices advance through testing, yet family connections subtly influence opportunities (see Elayne’s privileged access to ter’angreal)

- Information control: The Ajah system creates deliberate knowledge silos, mirroring modern corporate divisions

- Soft power dominance: Unlike the flashy One Power, the real authority lies in patronage networks and reputation management

This shift from plot-driven to systems-level reading reflects what literary scholars call paratextual awareness—the ability to see narratives as cultural artifacts rather than self-contained worlds.

Shadowspawn as Social Construct

The Trollocs I once dismissed as generic monsters now reveal disturbing allegorical dimensions. Jordan’s descriptions of their “beast-human” hybridity echo historical dehumanization tactics:

- Linguistic othering: Constant references to “stench” and “guttural growls” activate primal disgust responses

- Collective punishment: Villages are razed for potentially harboring Darkfriends, paralleling counterterrorism excesses

- Manufactured threat: The Dark One’s forces depend on human collaborators, much like real oppressive regimes

Modern fantasy has moved toward nuanced villainy (think The Broken Earth trilogy), but Jordan’s 1990 approach offers a case study in how epic fantasy traditionally constructed absolute evil.

Threads of Power in the Pattern

Most strikingly, the metaphor of women “weaving” the Pattern takes on new significance through feminist economic theory. The Wheel of Time operates on:

- Gendered labor division: Saidar vs. saidin mirrors historical divisions of “women’s magic” (healing, weather) vs. “men’s magic” (combat, construction)

- Epistemic privilege: Wisdom’s herb-lore and Aes Sedai’s political intuition represent alternative knowledge systems

- Reproductive symbolism: The Pattern’s endless turning evokes cyclical care work rarely acknowledged in heroic narratives

What once read as cool magic now feels like Jordan’s unconscious commentary on undervalued feminine labor—precisely the kind of buried theme that makes rereading books as an adult so rewarding.

Try This With Your Old Favorites

Next time you revisit a childhood book, watch for these sociological markers:

- Power logistics: Who controls resources (magic, land, information) and how?

- Boundary maintenance: How does the text define “us” vs. “them”?

- Silent labor: Whose work enables the hero’s journey but goes uncelebrated?

The Eye of the World still delivers dragon battles and prophecies, but it’s also a surprisingly rich text for analyzing how fantasy worlds encode real social dynamics—if you know how to look.

A Toolkit for Analytical Re-reading

Returning to beloved books with fresh eyes requires more than nostalgia—it demands new reading strategies. Having navigated my own journey from passive consumer to active analyst, I’ve distilled three practical steps for uncovering hidden dimensions in familiar texts.

Step 1: Mapping Ideological Apparatuses

Every fictional world operates on invisible assumptions. When rereading The Eye of the World, I applied Louis Althusser’s framework to identify how Jordan’s universe reinforces certain ideologies. Consider:

- Education Systems: The White Tower’s rigorous testing mirrors elite university admissions

- Religious Rituals: The Aes Sedai’s ceremonies function like state apparatuses

- Language Norms: The Old Tongue carries cultural capital akin to Latin in medieval Europe

Try This: In Game of Thrones, highlight moments where characters invoke “house words”—these are ideological tools maintaining feudal loyalty.

Step 2: Charting Power Relationships

Fantasy novels teem with political maneuvering we often overlook during first reads. Create a simple diagram while reading:

| Power Holder | Resource Controlled | Resistance Points |

|---|---|---|

| Aes Sedai | Magic/Information | Whitecloaks |

| Nobles | Land/Taxes | Commoners’ riots |

This reveals how The Wheel of Time‘s conflict stems from resource distribution—a concept I’d missed as a teen focused on magical battles.

Step 3: Interrogating Silenced Voices

As a social scientist, I now notice who isn’t speaking. In Asimov’s Foundation:

- The Galactic Empire’s collapse is told through elite perspectives

- Missing entirely: laborers maintaining hyperspace routes

- Absent debate: ethical implications of psychohistory’s determinism

Exercise: Pick any favorite novel and list three groups whose perspectives are marginalized. What changes if we center their experiences?

These techniques transformed my relationship with old favorites. Where I once saw only plot, I now uncover:

- Cultural commentary (How Otherland predicted digital class divides)

- Authorial blind spots (Gender dynamics in early Dragonlance)

- Historical parallels (Jonathan Strange‘s faerie colonialism)

The real magic happens when we bring our accumulated knowledge back to beloved texts. Your sociology degree, work experience, or even parenting insights all become analytical lenses waiting to be focused on familiar pages.

Next Step Challenge: Apply one technique this week to a childhood favorite. Notice how your professional expertise illuminates new patterns—whether you’re in healthcare, education, or tech. The books haven’t changed… but your ability to read them certainly has.

The Alchemy of Returning

Books are time machines—but we’re the ones who change. That worn paperback copy of The Eye of the World still smells like my childhood bedroom, its spine cracked at the same battle scenes. Yet the words now reveal patterns teenage me couldn’t perceive: how the Aes Sedai’s strict hierarchy mirrors medieval guild systems, why the Children of the Light function like ideological police. The story hasn’t altered, but my lens has sharpened into something resembling a sociologist’s field notebook.

Your Turn: The Analytical Re-reading Challenge

Here’s an experiment for your next commute or bedtime routine:

- Select a childhood favorite (I dare you to pick The Hunger Games)

- Arm yourself with one analytical dimension:

- Class struggle (Who controls Panem’s resources?)

- Performativity (How do Katniss’ survival skills differ from her ‘TV persona’?)

- Spatial politics (District 12 vs. The Capitol’s architecture)

- Read just Chapter 1—but read like you’re preparing for a book club with Karl Marx and Judith Butler

You’ll notice subtle details previously drowned out by plot adrenaline: the way Mayor Undersee’s daughter gets fresh bread while Gale’s family starves, how the ‘Reaping’ ceremony ritualizes oppression through pageantry. Suddenly, what felt like straightforward dystopian YA becomes a masterclass in societal control mechanisms.

The Ultimate Reader’s Riddle

When you reopen that childhood favorite—dog-eared Harry Potter or that His Dark Materials trilogy with soda stains on the maps—who exactly will be reading it? The version of you that first fell for Lyra’s lies? The college graduate who recognizes Pullman’s critique of institutionalized religion? Or some future self who’ll uncover layers none of us can yet see?

My copy of The Wheel of Time now lives between two bookends: a ticket stub from the 1998 bookstore signing where I met Robert Jordan, and a post-it with Bourdieu’s definition of cultural capital. That’s the magic of rereading books as an adult—we don’t just revisit stories, we archaeologically excavate our own evolving worldview.

So go dig up your literary time capsule. The person who packed it may surprise you.