The ventilator hissed its steady rhythm, a mechanical lullaby for my mother who lay motionless except for the faint tremors beneath her eyelids. That thin green line on the monitor kept drawing mountains and valleys, each peak a silent protest against the statistics. One in a hundred, they’d said. Not zero, not never, but one. A number that tasted like hospital antiseptic and sounded like the crinkle of consent forms.

Her skin felt like the paper she used for my wings when I was four – that crisp stationery from her writing desk, the kind that yellowed at the edges when left in sunlight. I remember how she’d scored the folds with her thumbnail, precise as a surgeon, while explaining lift and drag to a preschooler who just wanted to jump off the porch. Now her hands lay still, the veins mapping rivers the ventilator’s breath couldn’t navigate.

‘These things happen,’ the cardiac fellow had murmured, his eyes already scanning the next chart. The phrase hung between us like an unplugged monitor – all blank potential where meaning should have been. Outside, December forgot to bring its chill, leaving only a damp grayness that clung to the windows. People passed the bus stop in bursts of color and noise, their movements oddly segmented like stop-motion figures in a child’s flip book.

Somewhere between the third and fourth ventilator cycle, I noticed how the ceiling tiles resembled the paper we’d used for those wings. The same faint grain, the way they drank the fluorescent light. A nurse adjusted something near the IV pole, her shoes squeaking the same rhythm my mother’s chair used to make when she leaned over her poetry notebooks. The green line spiked, and for a breath I could almost see the shadow of wings reflected in the cardiac monitor.

What no one mentions about perioperative strokes is the silence. Not the machine noises or the shift change chatter, but the absence of that particular sound a mother makes when recognizing her child’s footsteps. The ventilator filled lungs but not spaces. When I pressed my palm to hers, the cold wasn’t the sharp winter kind from our old walks, but the slow seep of ink into paper when you’ve held the pen too long in one spot.

Down in the lobby, a man laughed into his phone – three sharp barks that didn’t sync with his smiling mouth. The automatic doors kept breathing in and out, in and out, like the machine upstairs keeping time with its own indifferent arithmetic. One in a hundred. Not never. Not zero. Just one green line on a screen, one set of paper wings dissolving in the rain.

The Arithmetic of Loss

The consent form felt heavier than its three pages should allow. My fingers left damp smudges on the paper as I traced the phrase ‘perioperative stroke’ followed by that cursed percentage: 1%. The number pulsed on the page like the heart monitor she’d soon be connected to, its clinical precision offering no comfort. The surgeon’s pen hovered over the dotted line, waiting.

‘Statistically speaking,’ he said, clicking his ballpoint absently, ‘your mother has a ninety-nine percent chance of waking up just fine.’ His voice carried the practiced calm of someone who’d said these words hundreds of times. The calculator in my head immediately started its cruel work – if this hospital performed ten heart surgeries weekly, that meant every two months someone’s loved one became this statistic.

A memory surfaced without warning: my mother at twelve years old, knees pressed into cold linoleum as she counted coins on her father’s casket. That same calculating look crossed her face decades later when helping me with third-grade arithmetic. ‘Numbers never lie,’ she’d say, tapping her yellowed plastic calculator with its fading orange digits. ‘But they never tell the whole truth either.’

The pen finally met paper. My signature bloomed blue ink across the line, the letters trembling like the green EKG trace I’d soon become obsessed with. Somewhere between the consent form’s legalese and the calculator’s beeps, probability transformed from abstraction to lived experience. That one percent stopped being a number and became my mother’s body on a ventilator, her eyelids fluttering as if reading invisible poetry beneath closed lids.

Outside the consultation room, a nurse laughed with a colleague about weekend plans. The sound fragmented against the hospital’s antiseptic walls, breaking into particles that hung suspended like the dust motes in my childhood kitchen. I remembered standing on a chair while my mother measured ingredients, her hands steady as she doubled the recipe. ‘Always account for the unexpected,’ she’d murmur when adding an extra pinch of salt. Now monitors would measure her every fluctuation, alarms ready to scream at the slightest deviation from acceptable parameters.

Back in pre-op, she reached for my hand with fingers already chilled by anticipation. ‘Did they tell you the one percent?’ she asked. When I nodded, she smiled the way she did when I brought home imperfect report cards. ‘Then we’ll just have to be the ninety-nine.’ Her certainty felt like paper wings – fragile, temporary, and miraculously capable of lifting us both.

The anesthesiologist arrived with his clipboard of questions. As he confirmed allergies and medications, I studied the veins on my mother’s wrist branching like rivers on an old map. Somewhere beneath that skin, plaque had built its silent barricades. Somewhere in that one percent margin, a blood clot might already be charting its catastrophic course. The calculator in my mind started running numbers again, dividing hope into smaller and smaller fractions until only this moment remained – her pulse beneath my fingertips, the citrus scent of hospital soap, and the unbearable lightness of probability before it becomes history.

Ventilator Nocturne

The ICU at night becomes a symphony of mechanical breathing. Each ventilator has its own rhythm, its own pitch, like instruments tuning before some terrible concert. My mother’s machine hums at 18 breaths per minute – a number I’ve come to know better than my own heartbeat. Between the whooshes and clicks, there are moments of perfect silence when I imagine she might wake up and ask why I’m staring at her eyelids.

At 2:17 AM, the pulse oximeter alarms. A nurse materializes to adjust the sensor without breaking stride. This happens seven times before dawn. I start to recognize the hierarchy of alerts – the staccato beep of low oxygen saturation sounds entirely different from the oscillating wail of blood pressure fluctuations. They’ve all become part of our nocturnal language.

Somewhere down the hall, a PA system pages Dr. Chen to the neuro ICU. The intercom crackles with the same distortion I remember from my elementary school loudspeakers. For three nights running, they’ve called this phantom doctor at precisely 3:42 AM. I wonder if he’s real, or just some audio placeholder meant to reassure families that the hospital never sleeps.

My mother wrote her first nocturne at sixteen, two years after her father’s funeral. I found the notebook when I was cleaning her study – delicate pencil marks scoring the line “midnight breathes in quarter notes.” Now I understand what she meant. The intervals between ventilator cycles measure out the night in perfect, artificial increments. Time here isn’t marked by clocks but by the cycling of pneumatic pumps.

At the nursing station, two residents discuss a perioperative stroke case over vending machine coffee. Their voices carry just enough for me to catch “basilar artery” and “1% mortality.” The statistics float in the air like the afterimage of a bright light. I press my palm against my mother’s foot – still warm, still alive despite the numbers.

Her eyelids flutter during REM sleep, creating a miniature cinema beneath thin skin. What dreams might come to someone suspended between pharmacological coma and neurological limbo? I imagine scenes from her childhood in rural Vermont: chasing fireflies, reciting Emily Dickinson to apple trees, folding origami cranes that would later inspire my paper wings.

The respiratory therapist adjusts the PEEP setting, and suddenly I’m eight years old again, watching my mother turn the tiny screw on my clarinet mouthpiece. “Too much resistance,” she’d say, “the music needs room to breathe.” Now machines make these adjustments with algorithmic precision, optimizing oxygen exchange while erasing the human touch from healing.

By 4 AM, the ICU achieves its closest approximation of quiet. The ventilators synchronize into an eerie chorus, their whoosh-exhales overlapping like waves on a shore. My mother’s cardiac monitor paints luminous green fractals across the darkened screen. I count each QRS complex like a metronome, clinging to the certainty of electrical impulses in a world where nothing else makes sense.

Dawn comes reluctantly through tinted windows. The night shift nurses report off in hushed tones, their replacements bright with artificial cheer. Someone’s phone plays a tinny pop song in a break room. For one disorienting moment, all the machines fall silent between cycles, and in that breathless interval, I swear I hear my mother humming.

Eyelid Cinema

Her eyelids flickered like an old film projector struggling to maintain frame rate. The nurses called it “spontaneous blinking” in their charts, but I timed the intervals – 7 seconds, then 4, then an agonizing 12 – as if she was editing her own dream sequences. Under those thin veined curtains, the rapid eye movements traced invisible arcs. Neurologists would later explain this as brainstem activity, but in that vinyl chair by her bedside, I became convinced she was watching something.

ICU delirium pamphlets warned about patients seeing tunnels or dead relatives, but no leaflet prepared me for the reverse phenomenon: the living watching the possibly-dying watch their private screening. The green heart monitor line spiked whenever her eyeballs jerked leftward. I started mapping the patterns, correlating directions with possible scenes: rightward for childhood memories (the time she fell through ice at eight), upward for motherhood moments (rocking me through asthma attacks), leftward for… something else entirely. The leftward tremors always came with a 0.3-second delay in the ventilator’s rhythm.

At 3:17 AM on the fourth night, her right eye opened just enough to reveal a sliver of white. Not the whole “awakening” drama TV shows love, but a fractional aperture, like a camera’s iris stuck between shots. The corneal reflection caught the overhead lights, creating a tiny cinema screen on her eyeball surface. In that curved projection plane, I saw distorted versions of ourselves – the warped silhouette of my hunched shoulders, the inverted image of the IV pole. For one hallucinatory minute, her cornea became a fish-eye lens documenting this nightmare.

When the neurology resident shone his penlight across her lids, he muttered “non-purposeful movement” and made a checkmark on his clipboard. But purpose isn’t always medical. Sometimes it’s the way her left eyelid twitched exactly when the cardiac monitor emitted its hourly chime, or how both eyes briefly stilled when I played her favorite Chopin nocturne on my phone. The prelude she’d once annotated with pencil marks now synchronized with her erratic REM cycles.

During shift changes, I’d eavesdrop on nurses debating whether coma patients dream. Their arguments always circled back to EEG readings and Glasgow scales. Nobody mentioned the more haunting possibility – that the eyelids might be viewing not dreams, but an alternate cut of reality. The version where she walked out of recovery smiling, where the 1% complication statistic remained abstract, where paper wings could still defy hospital gravity.

By week two, I’d developed a taxonomy of blinks: the “micro-flutter” (2-3 rapid vibrations during sponge baths), the “slow curtain” (one lid descending smoother than the other during blood draws), and the terrifying “sync drop” (both eyelids shutting simultaneously when alarms sounded). The night nurse showed me how corneal drying made the movements more pronounced, her explanation punctuated by the wet clicks of artificial tear applications.

Sometimes, when the breathing tube shifted, her lashes would catch strands of my hair as I leaned close. In those accidental embraces, I imagined her editing room – scissors snipping unwanted surgical scenes, splicing in outtakes from better days. The ventilator’s whoosh became projector noise, the bedrails the frame holding her fragile celluloid. And always, beneath those translucent screens, the mysterious screening continued – a private show for an audience of one, its reels spinning somewhere beyond the reach of penlights and probability charts.

The Invisible Storm

The neurologist’s fingers moved across the iPad screen with practiced swipes, pulling up black-and-white images of my mother’s brain. ‘See here,’ she said, circling a shadowy area with her stylus. ‘This occlusion in the middle cerebral artery – that’s our invisible storm.’ The term made me think of weather maps with their swirling red warnings, the kind my mother would interpret for me during childhood thunderstorms, softening their menace with stories of dancing raindrops.

On the screen, the angiogram showed branches like withered tree limbs, blood flow stuttering to a halt in pixelated increments. A 0.9% probability had materialized into this jagged topography. I remembered the consent form’s clinical phrasing: ‘perioperative stroke risks include but are not limited to…’ The words had floated past me then, weightless as the paper wings my mother once fashioned from grocery receipts.

‘It’s not like the movies,’ the neurologist continued. ‘No dramatic clutching of chests. The clot traveled silently during bypass, while everyone watched the more obvious metrics.’ Her explanation unspooled like one of those medical animations – the kind where cheerful red blood cells bump harmlessly against a cartoonish blockage. Reality was less colorful: a 2.3mm particle of calcified plaque breaking free, surfing the arterial highways until it lodged in the wrong neighborhood.

Through the ICU window, December light flattened everything into monochrome. I pressed my palm against the glass, feeling its cool resistance. At age six, during a summer downpour, my mother had placed my hand on the same windowpane to demonstrate how thunder worked. ‘The sky is just rearranging its furniture,’ she’d said, her breath fogging the glass. Now the monitors behind me emitted their own weather patterns – the arrhythmic beeping of the ventilator, the Doppler whoosh of the pulse ox sensor.

Nurses moved through their routines with meteorologist precision, tracking the numbers that rose and fell like barometric pressure. They spoke of ‘distal perfusion’ and ‘hemodynamic stability,’ terms that dissolved into the hum of machines. I watched the green ECG line scribble its unreadable poetry, each spike a failed attempt at communication. Somewhere beneath the sterile drapes, the same hands that had folded paper wings lay still, their creases filled with antiseptic orange.

In the family lounge, a television played muted news. A storm system crawled across the map, its pixelated edges blurring into the next region. I thought of how my mother would translate such forecasts into our private mythology – how she turned statistical inevitabilities into stories. The 30% chance of rain became ‘the clouds might cry today.’ The 1% complication rate became… what? A footnote? A folktale?

Back at the bedside, I traced the IV lines with my eyes, following their branching paths like rivers on some alien atlas. The invisible storm had made landfall in this room, its aftermath measured in milliliters per hour and milligrams per deciliter. Outside, real clouds sagged low, withholding their rain. The window reflected the heart monitor’s glow, superimposing its green rhythm over the parking lot below where people moved, oblivious, through the ordinary weather of their lives.

Non-Player Characters

The hospital cafeteria hummed with the kind of conversations that never seemed to progress. I watched a woman in a pink cardigan stir her coffee for the third time without drinking it, her spoon clinking against the ceramic in perfect 4/4 time. At the adjacent table, a man recited his wife’s medication schedule to an uninterested wall. These were the background characters in my new reality – a world where everyone moved with programmed gestures while I remained stuck in some glitched player mode.

Medical trauma does something peculiar to your perception of crowds. The laughing couple by the vending machine didn’t seem to possess full autonomy; their joy played on loop like NPC dialogue in a poorly coded game. When the man in scrubs bumped into my chair without apology, I half-expected a text bubble to appear above his head: “Sorry, in a hurry!” with three predetermined response options flashing in my vision.

I counted seventeen distinct conversations about parking validation. The recursion of it all – the way every family seemed to be having identical discussions about cafeteria food, doctor rounds, and insurance forms – made me wonder if we’d all been assigned the same basic dialogue tree. My fingers traced the edge of the consent form in my pocket, the one where I’d initialed next to “1% risk of perioperative stroke” without truly comprehending that percentage could manifest as my mother’s still body on a ventilator.

At the coffee counter, a barista asked a man about his day. Three times in two hours I heard him respond with the same inflection: “Just waiting on test results.” His character hadn’t been programmed with alternate responses. None of us had. We were all running the same hospital visitation algorithm:

- Receive devastating news

- Seek caffeine

- Pretend to understand medical jargon

- Repeat

Through the cafeteria windows, I watched real people living real lives beyond the hospital walls. A jogger adjusted her headphones. A businessman checked his watch. Their movements contained the fluid randomness my mother’s eyelids had before the stroke – that beautiful, chaotic autonomy we never appreciate until it’s reduced to a ventilator’s mechanical rhythm.

The pink-cardigan woman finally drank her coffee. As she stood to leave, I noticed her hospital ID bracelet matched mine. For the first time, our eyes met with something like recognition – two player characters momentarily seeing through the simulation. Then the automatic doors swallowed her, and I was alone again with the NPCs.

The Dissolving Wings

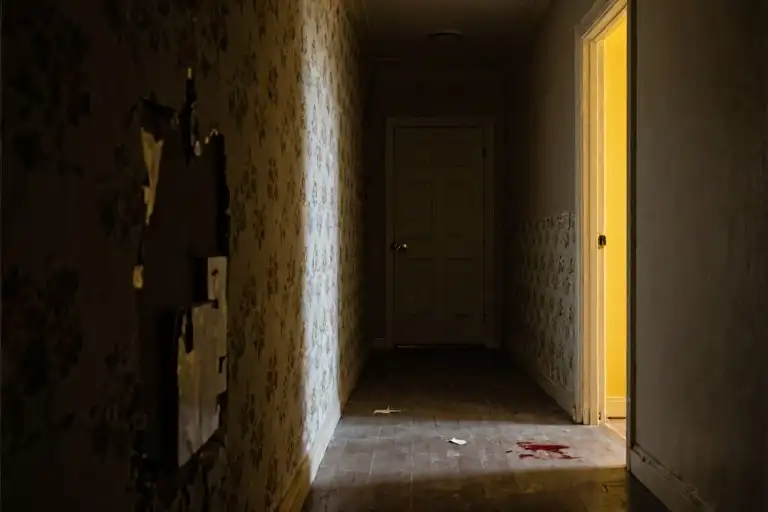

The December rain fell in slow motion, each drop pausing mid-air before shattering against the pavement. I stood at the bus stop with my collar turned up, watching the paper wings in my hands dissolve into translucent pulp. The same wings she’d made me twenty-three years ago from typing paper and laundry line string, now returning to the elements as her heartbeat flickered on that green-lit monitor three floors above me.

A bus hissed to a stop, its doors exhaling warm air that smelled of wet wool and diesel. Inside, passengers shook umbrellas with the mechanical precision of stop-motion animation. Their laughter came in delayed bursts, like a badly dubbed film. I thought of her eyelids fluttering in that sterile room – REM sleep or desperate signaling? The doctors called it ‘saccadic movements,’ but I knew better. My mother had always communicated in metaphors.

At four, I’d believed those paper wings could make me fly. She’d knelt beside me in her floral housecoat, the one with ink stains on the pocket from her poetry notebooks, carefully folding the edges to mimic feathers. ‘The secret,’ she’d whispered, taping the final strand, ‘is in the angle of ascent.’ Later that afternoon, I’d jumped from the porch steps and torn them on the rose bushes. She’d simply gathered the soggy fragments and said, ‘Next time we’ll use wax paper.’

Now the hospital’s glass doors slid open behind me, ejecting another family into the unreal world. A man clutched a plastic bag of belongings – someone’s slippers, a half-read magazine – his face the flat gray of overdeveloped film. We exchanged the look particular to our tribe: people who’d memorized the cadence of ventilator alarms, who could tell time by shift changes rather than daylight.

The rain intensified, blurring the hospital’s neon cross into a streak of arterial red. I watched it bleed down the window of the departing bus as my mother’s final poem played in my head, the one she’d written after my father left: The heart keeps beating after the story ends / Green lines on a black screen / All those unfinished sentences.

Back in ICU, her fingers twitched when I placed the remnants of the wings on her bedside table. The nurse said it was just spinal reflexes, but I saw the corner of her mouth lift – the same barely-there smile she’d given when I brought her dandelions instead of roses. On the monitor, the green line spiked briefly before settling into its new, slower rhythm.

Through the window, the storm had turned the parking lot into a negative of itself – white lines glowing against suddenly black asphalt. I pressed my palm against the glass and imagined her hand on the other side, cold but still soft. Somewhere beyond the rain, a child was laughing. Somewhere beyond the ventilator’s steady hiss, my mother was making wings from whatever materials the universe provided.