The phrase “War is Peace” glows ominously from the pages of 1984, its paradoxical brilliance undimmed by seventy-five years of history. As we approach the 75th anniversary of George Orwell’s death in January 2025, these three words pulse with renewed urgency in an era of algorithmic manipulation and digital surveillance. Orwell’s masterpiece, published mere months before his tuberculosis-ravaged body succumbed at 46, wasn’t merely fiction—it was a fever chart of the 20th century’s political maladies, written by a man who’d endured war’s crucible and personal tragedy’s relentless grind.

Few literary works have permeated global consciousness like 1984. From courtroom citations to Silicon Valley boardrooms where “Orwellian” gets tossed like rhetorical confetti, the novel’s concepts—thoughtcrime, Newspeak, the ever-watching telescreen—have become shorthand for modern anxieties. Yet behind Winston Smith’s rebellion against Big Brother lies a more intimate story: how a wounded idealist transformed personal suffering into prophetic art.

Orwell’s journey from London literary circles to the storm-lashed isolation of Scotland’s Jura Island mirrors his characters’ psychological odysseys. The same V-1 rocket that obliterated his Islington flat in 1944 didn’t just destroy a home—it shattered the last illusions of a writer already reeling from his wife Eileen’s sudden death during routine surgery. Holding their adopted son Richard amidst London’s rubble, Orwell embodied his own later observation: “We sleep soundly in our beds because rough men stand ready in the night to visit violence upon those who would do us harm.” Except now, the violence had visited him.

This 75th anniversary isn’t merely about commemorating a literary giant—it’s about confronting why 1984 sells out during every political crisis, why “Orwellian” trends whenever governments expand surveillance powers. As predictive algorithms and deepfake technologies blur reality, Orwell’s warning about “the mutability of the past” feels less like dystopian fiction and more like tomorrow’s news briefing. His genius lay in recognizing that totalitarianism evolves faster than human vigilance; today’s convenience (voice-activated assistants, social credit systems) becomes tomorrow’s tyranny.

Seventy-five winters after Orwell’s death, as we navigate misinformation epidemics and AI-generated propaganda, revisiting his work becomes an act of intellectual self-defense. Not because 1984 offers solutions, but because it sharpens our questions: When does security become oppression? How thin is the line between connectivity and control? And most crucially—how does a civilization retain its humanity when technology outstrips its ethics? These are the conversations Orwell compels us to have, now more than ever.

The Shattered London: How War and Loss Destroyed a Writer

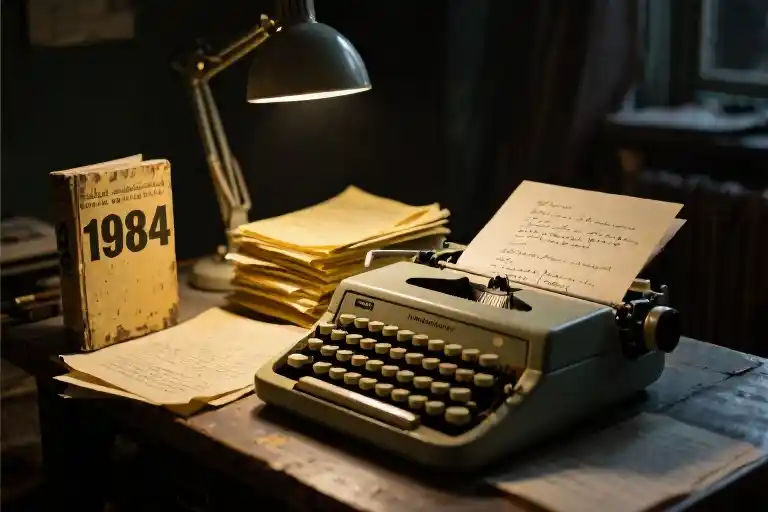

On a quiet afternoon in June 1944, a V-1 flying bomb changed George Orwell’s life forever. The explosion that ripped through his London flat at Mortimer Crescent didn’t just destroy physical possessions – it obliterated the last remnants of his pre-war existence. Manuscripts, letters, and the writer’s beloved typewriter were buried under rubble, much like Orwell’s own psyche would soon be buried under successive layers of personal tragedy.

This wartime trauma became the first fracture in what would become Orwell’s profoundly broken world. The man who had moved among London’s literary elite, hosting spirited debates in book-lined parlors with his wife Eileen by his side, now found himself clutching his adopted son Richard while navigating bombed-out streets. The contrast couldn’t have been sharper – from the intellectual salons where Orwell’s sharp wit shone, to the desperate reality of a single father rationing powdered eggs in a city under siege.

Then came the blow that would haunt Orwell’s remaining years. In March 1945, during what should have been a routine hysterectomy, Eileen Blair (née O’Shaughnessy) died under anesthesia. The suddenness of her passing at just 39 years old left Orwell reeling. Those familiar with his work can’t help but see echoes of this personal betrayal by fate in 1984’s Julia – a character who becomes Winston Smith’s emotional anchor before ultimately failing him. Orwell’s private correspondence reveals how Eileen’s death fundamentally altered his worldview, writing to friends about feeling ‘shipwrecked’ in a world that no longer made sense.

The care of their adopted son Richard became Orwell’s sole responsibility overnight. Letters from this period show a man torn between paternal duty and creative despair. In one particularly poignant note to his friend Arthur Koestler, Orwell confessed: ‘I keep writing because I must – for Richard’s future, if not my own.’ This tension between present suffering and concern for future generations would later crystallize in 1984’s harrowing depiction of a world where children betray parents and hope itself becomes treasonous.

London, once the vibrant backdrop to Orwell’s literary success, now represented everything he needed to escape. The bombed-out buildings mirrored his internal landscape; the constant air raid sirens echoed his psychological turmoil. It was during these walks through postwar London’s ruins that many scholars believe Orwell first conceived the blasted urban hellscape of Airstrip One in his seminal novel. The physical destruction around him became metaphor for the ideological destruction he feared was coming.

What makes Orwell’s experience particularly heartbreaking is how it transformed but didn’t break his humanist spirit. Even while drafting literature’s darkest dystopia, he maintained correspondence with Richard’s teachers, fussing over the boy’s Latin lessons. The same hand that penned ‘If you want a vision of the future, imagine a boot stamping on a human face – forever’ also wrote tender notes to his son about fishing trips they’d take once his health improved. This duality – the ability to stare unflinchingly at humanity’s darkest potentials while clinging to fragile personal connections – would become Orwell’s greatest literary gift.

As we examine this painful period in Orwell’s life, we begin to understand how personal catastrophe fueled prophetic creativity. The writer who gave us Big Brother first knew surveillance of a different kind – the watchful eyes of a child depending on him, the judgmental gaze of a society that expected him to maintain stiff upper lip while his world collapsed. From these experiences emerged not just a great novel, but a warning etched in the fire of personal suffering – one that continues to resonate 75 years after his death.

The Solitude of Jura: Forging 1984 in Isolation

George Orwell’s arrival on the remote Scottish island of Jura in 1946 marked both an escape and a confrontation. The writer who had once thrived in London’s literary circles now sought refuge in a place where electricity was nonexistent, supplies arrived by unpredictable fishing boats, and the nearest telephone was 25 miles away. This radical shift from urban intellectual to island recluse would become the crucible for one of literature’s most powerful warnings about totalitarianism.

A Writer’s Spartan Existence

The Barnhill farmhouse where Orwell settled with his young son Richard presented challenges that would have deterred most. With no running water or reliable heat source, daily life revolved around basic survival. Orwell took to the rhythms of island living – cutting peat for fuel, hauling water from the well, and maintaining a vegetable garden against Jura’s relentless winds. These physical demands strangely complemented his creative process, the austerity of his surroundings mirroring the bleak clarity of his emerging novel.

Visitors described the primitive conditions with amazement. One guest recalled Orwell typing at a makeshift desk while wrapped in multiple sweaters against the cold, his breath visible in the unheated room. The isolation was both chosen and necessary – away from London’s distractions and the growing fame that followed Animal Farm’s success, Orwell could focus completely on what he called “my mysterious book.”

Tuberculosis and the Race Against Time

What Orwell hadn’t anticipated was how Jura’s harsh climate would accelerate his declining health. Diagnosed with tuberculosis before moving to the island, his condition worsened in the damp environment. By 1947, violent coughing fits left him bedridden for weeks, the blood-stained handkerchiefs piling up beside his manuscript pages. His doctors urged a return to civilization for proper treatment, but Orwell stubbornly refused – this book had become more important than his survival.

In a cruel twist of fate, the disease that was killing him also sharpened his writing. The feverish intensity of his work sessions produced some of 1984’s most haunting passages. Winston Smith’s chest pains in the novel mirrored Orwell’s own; the Ministry of Love’s interrogation scenes carried the visceral terror of a man intimately acquainted with physical suffering. As his body failed, his creative vision grew more precise.

The Birth of Doublethink

The manuscript’s evolution reveals Orwell’s extraordinary attention to linguistic precision. Early drafts show him struggling to define the Party’s mental control mechanisms, initially calling them “duality” and “controlled schizophrenia.” The breakthrough came during a sleepless night in 1948 when he scrawled “DOUBLETHINK” in the margin – a term that would enter the global lexicon. Subsequent pages bear witness to his meticulous refinement, crossing out entire paragraphs only to rewrite them with surgical clarity.

Orwell’s working methods were characteristically methodical. He maintained detailed notebooks tracking the dystopia’s rules – Newspeak’s shrinking vocabulary, the telescreens’ surveillance capabilities, even the Party’s exact calorie rationing. These weren’t speculative flourishes but calculated warnings, each element grounded in his observations of wartime propaganda and postwar political shifts.

Legacy in the Peat Smoke

Today, visitors to Jura can still see the tiny bedroom where Orwell completed his masterpiece. The manual typewriter sits exactly where he left it, facing a window that overlooks the same storm-tossed sea he watched while imagining Room 101. There’s something profoundly moving about this juxtaposition – one of literature’s darkest visions created in a place of raw natural beauty.

The irony isn’t lost on those who know Orwell’s story. The man who warned about omnipresent surveillance chose to write that warning in perhaps the last place in Britain where one could truly disappear. In our age of constant connectivity, there’s poetic power in remembering that 1984 was born in disconnected solitude, its author literally coughing his life into the pages that would outlive him.

75 Years Later: Is Orwell’s Dystopia Our Reality?

Seventy-five years after George Orwell’s passing, the haunting words of 1984 echo with unsettling relevance. The novel’s fictional concepts—Newspeak, thoughtcrime, and telescreens—no longer feel like distant warnings but rather like distorted reflections of our digital age.

The New Newspeak: From Fiction to Filtered Reality

Orwell’s invented language ‘Newspeak’ was designed to eliminate rebellious thoughts by shrinking vocabulary. Today, we witness a different kind of linguistic control: algorithmic content moderation. Social platforms automatically flag or shadowban terms ranging from medical keywords to political slogans, creating an invisible lexicon of ‘unwords.’ A 2023 Stanford study revealed that 68% of major platforms employ AI-driven censorship tools—not unlike 1984‘s ‘Ministry of Truth’—though ostensibly for harm reduction rather than thought suppression.

This linguistic sanitization extends beyond tech. Corporate ‘doublespeak’ (a term popularized by Orwell) thrives in phrases like ‘rightsizing’ for mass layoffs or ‘enhanced interrogation’ for torture. The parallels grow starker when examining state-level language policing; China’s social credit system famously blocks searches for ‘Tiananmen Square,’ while Russia’s 2022 media law criminalizes calling the Ukraine invasion a ‘war.’

Surveillance Society: Big Brother or Big Data?

When Orwell described telescreens that watched citizens in their homes, he envisioned a crude 1940s version of what we now call IoT devices. Modern smart homes—with always-listening voice assistants, doorbell cameras, and fitness trackers logging biometric data—have normalized surveillance in ways even Winston Smith might find excessive.

Consider these chilling data points:

- The average urban resident is captured by CCTV 300+ times daily (UK Home Office, 2023)

- 80% of smartphone apps share user data with third parties (MIT Tech Review)

- Predictive policing algorithms disproportionately target minority neighborhoods

Yet unlike 1984‘s overt oppression, today’s monitoring wears a velvet glove. We voluntarily trade privacy for convenience—posting meals on Instagram, sharing locations with friends, or allowing apps to scan our faces. The dystopia arrived not with jackboots but with Terms of Service agreements.

Global Tributes: Reading 1984 Under Watchful Eyes

On the 75th anniversary of Orwell’s death, readers worldwide staged poignant acts of remembrance. In Tokyo, book clubs gathered beneath security cameras to read passages about perpetual surveillance. Berliners projected quotes like ‘Ignorance is Strength’ onto the remains of the Berlin Wall. Most strikingly, Hong Kong protesters during the 2019-2020 demonstrations used 1984 as a cipher—holding copies aloft as silent critiques of China’s encroaching control.

These commemorations reveal the novel’s enduring power as both literature and protest tool. As British novelist Zadie Smith observed: ‘Orwell taught us that the greatest threat to freedom isn’t the loud tyrant but the quiet erosion of words, privacy, and truth.’

The Unanswered Question

Seventy-five years later, we’re left grappling with Orwell’s central paradox: does 1984 remain fiction because we heeded its warnings, or have we simply crafted a more palatable version of its horrors? The answer may lie in our willingness to recognize the dystopia already here—not in Ministry of Truth bulletins but in TikTok’s algorithmically narrowed worldviews, not in Room 101’s rats but in dopamine-driven doomscrolling.

Perhaps Orwell’s true legacy isn’t predicting the future but giving us the vocabulary to question it. As you finish this article, consider how often you’ve encountered these modern parallels—and what Winston Smith might say about our tech-saturated lives.

Epilogue: The Immortality of Ideas

George Orwell’s final words, “At 50, everyone has the face he deserves,” carry a weight that transcends time. But it was his private journal entry from 1949 that truly encapsulates his legacy: “Men are mortal, but ideas are not.” As we stand 75 years after his passing, this dichotomy between human fragility and intellectual endurance remains the most poignant lens through which to view his life’s work.

The question lingers in our digital age – when we commemorate Orwell today, are we looking backward at historical warnings or forward at emerging dangers? The answer likely lies somewhere in between. His writings serve as both a gravestone for past atrocities and a lighthouse against future ones. In an era where facial recognition scans crowds and algorithms predict behaviors, the line between Orwell’s fiction and our reality grows curiously thin.

Consider how casually we now accept terms like “alternative facts” – a perfect modern incarnation of Newspeak. Or how social media platforms subtly reshape our memories through selective content curation, mirroring the Ministry of Truth’s memory holes. These parallels aren’t coincidental; they demonstrate Orwell’s uncanny ability to diagnose humanity’s recurring ailments.

Yet perhaps Orwell’s greatest gift wasn’t prophecy, but perspective. His works remind us that power structures may change their uniforms, but rarely their appetites. That surveillance might evolve from telescreens to smartphones, but the fundamental struggle for autonomy persists. This is why students still analyze Animal Farm’s allegory, why journalists reference “Orwellian” overreach, why protesters hold up 1984 at privacy rallies.

As you close this reflection on Orwell’s life and legacy, we leave you with one final question to ponder: In a world increasingly shaped by invisible algorithms and decentralized power, does reading Orwell today make us more informed citizens or more anxious ones? The answer may say more about our current moment than about the books themselves.

What remains undeniable is that the frail man who coughed blood onto his typewriter in a remote Scottish cottage somehow outlived empires. His body succumbed to tuberculosis at 46, but his ideas continue breathing, evolving, and challenging us three-quarters of a century later. That’s the paradox Orwell represents – the mortal writer who achieved immortality not through elixirs or monuments, but through the simple, devastating power of truth-telling.