The sweater clung to my skin despite the calendar claiming it was midsummer. Every afternoon around 3 PM, the same ritual – reaching for the cardigan draped over my office chair, rubbing my hands together, wondering why no one else seemed bothered by the Arctic blast from the vents above. For years I assumed my thermostat war was personal, some peculiar quirk of biology until the day my fingers stumbled upon a dog-eared copy of ‘Invisible Women’ during lunch break.

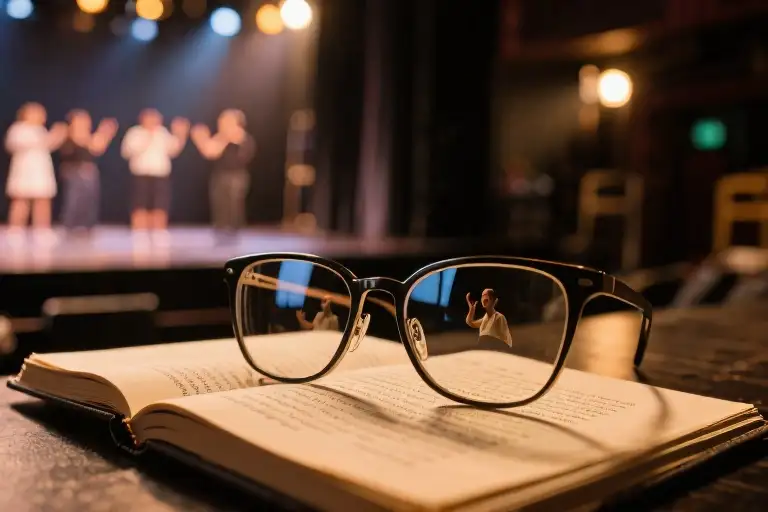

By page 23, the shivers running down my spine had nothing to do with the AC. Caroline Criado Perez’s research laid bare the uncomfortable truth: office temperatures worldwide are calibrated to the metabolic rate of a 40-year-old, 154-pound man. That moment of revelation felt like finally getting the correct prescription for glasses after squinting at blurred signs for decades. The world snapped into sudden, infuriating focus.

What startled me most wasn’t the temperature data itself, but how thoroughly I’d internalized the discomfort as personal failing. Like countless women, I’d perfected the art of layering without questioning why modern workspaces required such adaptations. The book’s central thesis – that male-as-default thinking permeates everything from thermostat settings to urban planning – explained so many daily friction points I’d dismissed as individual inconveniences.

This cognitive shift mirrors what psychologists call ‘paradigm blindness’ – the inability to see systemic patterns until someone provides the right framing. Perez’s work does precisely that, transforming isolated annoyances into recognizable symptoms of a larger gender data gap. Her research reveals how neutral-seeming standards often encode biological assumptions that exclude women, from the height of kitchen counters to the algorithm weighting job applications.

That initial office temperature case study operates like a diagnostic key. Once you recognize this single instance of design bias, you start spotting the pattern everywhere: public benches too deep for shorter limbs, smartphone screens requiring hand spans few women possess, voice recognition software struggling with higher vocal registers. The cumulative effect resembles living in a house where all the doorframes are six inches too low – you can function, but only through constant, exhausting accommodation.

What makes these revelations simultaneously validating and unsettling is their sheer banality. There’s no mustache-twirling villain behind the temperature controls, just generations of designers working from unexamined norms. This absence of malicious intent actually compounds the problem, making the biases harder to identify and eradicate. Like fish unaware of water, we’ve accepted male-default settings as simply ‘how things are’ rather than conscious design choices favoring one group.

The glasses metaphor holds particular power because vision correction is both irreversible and universally understood. You can’t unsee the thermostat wars as anything but systemic bias once you comprehend the underlying mechanism. This creates what gender researchers call the ‘curse of knowledge’ – the inability to revert to previous unawareness, which becomes both a burden and catalyst for change.

The Hidden Bias in Everyday Norms

It starts with small discomforts. The persistent chill in your office that has you reaching for a cardigan in midsummer. The way your feet dangle uncomfortably from chairs designed for taller frames. These aren’t personal quirks or individual sensitivities – they’re systematic oversights baked into our environments through decades of design decisions that took male physiology as the universal standard.

Take office temperatures. Most buildings maintain thermostats set to the metabolic rate of a 40-year-old, 154-pound man. This formula, developed in the 1960s, ignores fundamental biological differences – women typically have slower metabolic rates and higher body fat percentages. The result? A 2015 study published in Nature Climate Change found that most office buildings set temperatures about 5 degrees Fahrenheit too cold for women’s comfort. That’s not a malfunction; it’s a design feature.

The lighting in workplaces tells a similar story. Standard office lighting assumes the visual acuity of younger male eyes. Research from the Lighting Research Center shows women generally need brighter light for equivalent visual performance, particularly as they age. Yet lighting systems rarely account for this, creating environments where women strain to read documents under illumination calibrated for their male colleagues.

Public spaces reveal even more glaring oversights. The eternal women’s restroom queue isn’t just bad luck – it’s basic math. Building codes typically mandate equal square footage for men’s and women’s restrooms, ignoring that women take approximately 2.3 times longer to use facilities. When the University of Waterloo analyzed this disparity, they found women’s restrooms needed about twice as many fixtures to achieve equal wait times. This oversight extends to transportation design too – from subway turnstiles too narrow for strollers to seat belts that don’t accommodate pregnancy.

Workplace tools often follow the same biased blueprint. Personal protective equipment frequently comes in sizes based on male anthropometric data, leaving women with ill-fitting gear that compromises safety. A 2019 Government Accountability Office report found 76% of female firefighters reported issues with properly fitting protective clothing. Even in digital spaces, default settings show bias – voice recognition systems trained primarily on male voices show significantly higher error rates for female users.

These aren’t isolated incidents but symptoms of a deeper pattern. For nearly two millennia, since Vitruvius first proposed using the male form as architectural ideal, we’ve treated the male body and experience as humanity’s default setting. Medical textbooks illustrate diseases on male bodies. Car safety tests use crash dummies modeled on male physiques. Even smartphone sizes were originally designed to fit comfortably in male hands. This unexamined assumption shapes everything from product design to urban planning, creating a world where women constantly adapt to systems not built for them.

The cumulative effect is both practical and psychological. Beyond physical discomfort, these design choices send a subtle but persistent message: your needs are exceptions rather than norms. But as awareness grows, so does the opportunity to challenge these defaults. Recognizing these biases isn’t about assigning blame but about seeing systems clearly – the essential first step toward redesigning them.

When Data Fails Half the Population

The stethoscope pressed against my chest felt colder than usual. ‘Your symptoms don’t match typical heart attack indicators,’ the ER doctor said, scanning my chart. What he didn’t say – what the medical textbooks didn’t tell him – was that nearly 70% of cardiovascular research historically used male subjects. My pounding heart and nausea were textbook female cardiac symptoms, invisible in studies designed around male physiology.

This isn’t just about hospital rooms. Our cities pulse with the same data bias. Urban planners track commuter patterns religiously, yet somehow miss the millions of school runs and pharmacy trips predominantly made by women. Transportation maps glow with data points tracing office-bound routes at 8am, while the crisscrossing paths of caregivers remain uncharted territory.

The Sample Size Deception

Medical research’s gender data gap isn’t accidental. Until the 1990s, women were routinely excluded from clinical trials due to ‘hormonal complications’ – as if male biology represented some neutral baseline. The consequences linger: women experience adverse drug reactions nearly twice as often as men. Our medications are essentially designed through a keyhole view of human biology.

Pharmaceutical labs aren’t alone in this narrow vision. Tech companies train facial recognition on predominantly male image sets, resulting in error rates up to 34% higher for women. Voice assistants struggle with higher-pitched voices not because of technical limitations, but because the training data sounded different.

The Variables We Never Measure

City councils proudly display traffic flow heatmaps when proposing new infrastructure. These colorful dashboards rarely account for trip-chaining – that intricate dance of dropping kids at school, hitting the grocery store, then swinging by an aging parent’s home before work. Women complete 75% more multi-stop trips than men, yet transportation models still optimize for direct commutes.

Even disaster preparedness falls prey to this blindness. Early tsunami warning systems in Southeast Asia were placed in fishing ports – spaces predominantly used by men. The women gathering shellfish along quieter stretches of beach received no alerts when the 2004 waves came.

Algorithms Amplify What We Ignore

Machine learning doesn’t eliminate human bias; it entrenches it. When HR software trained on decades of male-dominated promotion patterns ‘learns’ what leadership looks like, qualified women get filtered out before human eyes ever see their resumes. Each rejection reinforces the algorithm’s original flawed assumptions.

This feedback loop extends beyond hiring. Search engines associate ‘computer programmer’ with male-coded images 75% more frequently than female. Predictive policing tools deployed in predominantly minority neighborhoods create self-fulfilling prophecies of criminality. The data doesn’t lie – it simply repeats our past mistakes with terrifying efficiency.

The Staggering Cost of Missing Data

The economic toll of these oversights would shock any accountant. Gender-blind product design leads to returned purchases and lost customers – pharmaceutical companies lose approximately $500 million annually on drugs women can’t tolerate. Cities waste millions on underutilized infrastructure that doesn’t serve residents’ actual movement patterns.

But the human costs cut deeper. Misdiagnosed heart attacks kill thousands of women needlessly each year. Public spaces that feel unsafe limit mobility and opportunity. Perhaps most insidiously, generations of girls internalize that discomfort is their fault – that constantly adjusting to ill-fitting systems constitutes normal life rather than systemic failure.

These aren’t glitches in otherwise functional systems. They’re the inevitable result of treating half the population as statistical noise rather than essential data points. Every time we accept ‘that’s just how the data looks,’ we cement a world designed by and for a narrow slice of humanity.

The Bias-Busting Toolkit: From Awareness to Action

That moment when you realize your office isn’t actually broken – it was just never built for you – can leave you frozen in more ways than one. The good news? We’re not powerless against these invisible defaults. Change starts with recognizing patterns, then progresses through concrete steps anyone can take.

Personal Power Moves

Keeping a bias observation journal transforms vague discomfort into actionable data. Try this format:

- Situation: Tuesday 2pm, shivering at desk despite cardigan

- Physical reaction: Typing speed decreased 20% due to stiff fingers

- Comparative note: Male colleagues in short sleeves complaining it’s ‘too warm’

- System connection: Building thermostat set to 21°C (optimal for male metabolic rate)

When addressing temperature complaints, shift from subjective (“I’m cold”) to objective framing:

“Research shows current settings favor male metabolic rates by 3-5°C. Could we pilot a 23°C zone for two weeks and measure productivity impacts?” This approach uses inclusive design language rather than gender confrontation.

Organizational Change Levers

The gender data gap persists because nobody thinks to ask. Start collecting these metrics:

- Facility feedback: Track temperature complaints by gender/department

- Equipment audits: Percentage of protective gear fitting female staff properly

- Space utilization: Meeting room chair adjustments needed per user group

One European bank’s pilot program tells an encouraging story. After analyzing thermostat complaints (87% from women), they implemented dynamic zoning:

- Core working hours: 22-23°C

- Post-lunch hours: 21°C (accommodating metabolic shifts)

- Conference rooms: Individual climate controls

Result? 31% reduction in temperature-related HR complaints and unexpected 6% rise in afternoon meeting productivity.

Civic Engagement Made Simple

Public infrastructure changes begin with showing up. Preparation tips for design hearings:

- Bring visuals: Overlay female body measurements on proposed bus seat designs

- Cite precedents: Vienna’s gender-mainstreaming in public transit reduced women’s travel time by 19%

- Propose metrics: “Can we measure staircase usability by stroller-pushing testers?”

The Gender-Smart Design Awards showcase brilliant fixes worldwide, from Tokyo’s pregnancy-friendly subway seats to Barcelona’s shadow-mapped playgrounds. Following these innovators proves inclusive design isn’t theoretical – it’s already happening in pockets of brilliance we can replicate.

What makes these tools work is their specificity. We’re not fighting some vague notion of ‘bias’ – we’re methodically exposing how male-default thinking manifests in thermostat settings, chair heights, and algorithm training sets. Each small correction makes the invisible visible, until one day we’ll look back amazed we ever accepted a world designed for half its population.

The Lens That Can’t Be Unseen

That moment when the world snaps into focus stays with you. Like finally getting the right prescription for your glasses, the revelation about systemic gender bias alters how you see everything – the office thermostat, the smartphone in your hand, the sidewalk outside your apartment. The clarity is equal parts gift and burden.

What makes Criado Perez’s work so transformative isn’t just the shocking statistics (though those matter), but the irreversible perspective shift. Once you notice how many everyday systems assume male as default – from voice recognition software trained primarily on male voices to crash test dummies modeled on male physiques – you start seeing the pattern everywhere. The book doesn’t just present information; it rewires your perception.

This new vision demands action. Start small: tomorrow morning, take three minutes to notice design choices around you. Is the shared kitchen’s highest shelf unreachable for most women? Do meeting room chairs leave shorter colleagues’ feet dangling? Document one observation using your phone’s notes app – concrete examples become powerful change tools.

Consider Tokyo’s Naka-Meguro Station redesign as proof of what’s possible. When architect Yoshihiko Sano intentionally consulted female commuters, the upgrades included:

- Brighter lighting at pedestrian pathways

- Elevators accommodating strollers and wheelchairs

- Rest areas with seating near restrooms

These modifications didn’t just help women – they created better urban experiences for everyone.

Systemic change begins when enough people refuse to accept discomfort as normal. Your documented observations, shared with colleagues or local representatives, become the data that challenges the status quo. The first step is trusting what you now see clearly.