The heavy silence that settled over Chicago’s Music Box Theatre after the screening of No Other Land spoke louder than any applause. Winter coats rustled as audience members sat motionless, some clutching unfinished coffee cups that had gone cold during the film’s runtime. In that suspended moment between the final frame and the house lights coming up, something rare occurred in modern cinema – a collective breath held by hundreds of strangers, united in visceral understanding of the documentary’s unflinching truth.

This Oscar-winning film, honored with over 60 international awards including the Academy Award for Best Documentary Feature, achieves what few works about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict manage – it transforms geopolitical complexity into human-scale stories without losing historical urgency. Directors Yuval Abraham and Basel Adra, an Israeli and Palestinian journalist team, created more than a chronicle of occupation; they built a bridge between narratives too often kept segregated.

What makes No Other Land exceptional isn’t just its harrowing footage of home demolitions in Masafer Yatta or its intimate access to daily life under occupation. The film’s revolutionary act lies in its very existence as a collaborative project between filmmakers from opposing sides of one of the world’s most polarized conflicts. When Abraham speaks of “stronger voices together” during their Oscar acceptance speech, he references both their creative partnership and the film’s central thesis: that mutual recognition precedes any possibility of justice.

The documentary’s impact becomes measurable not just in trophies but in those silent theater moments – the suspended coffees, the tissues crumpled in fists, the delayed exit of audiences needing extra minutes to compose themselves. These reactions suggest something more profound than artistic appreciation; they signal the stirring of moral reckoning. As the BDS protesters’ brief interruption underscored, this isn’t cinema that allows passive consumption. It demands response.

Perhaps this explains why No Other Land became the highest-grossing documentary among this year’s Oscar nominees despite minimal studio backing. Audiences recognize when art transcends entertainment to become testimony – when a film doesn’t just depict reality but alters the viewer’s relationship to it. The awards trajectory from film festivals to the Dolby Theatre mirrors how personal stories can amplify into global conversations, proving that ethical filmmaking still holds power to disrupt comfortable ignorance.

The Frozen Frame: An Unsettling Cinematic Experience

The rustling of winter coats and the clinking of abandoned coffee cups were the only sounds breaking the silence at Chicago’s Music Box Theatre. This wasn’t your typical post-screening chatter – the audience had just witnessed ‘No Other Land,’ and the weight of its message left everyone speechless.

In most theaters, credits rolling signals an immediate return to reality – phones light up, conversations spark, seats flip back with familiar thuds. But here, something extraordinary happened. The documentary’s final frames faded to black, and for nearly ninety seconds, not a single person moved. The air felt thick with unprocessed emotions, the kind of silence that speaks louder than applause.

Then, from the back row, a voice pierced the stillness. ‘Free Palestine!’ shouted a young activist, quickly joined by others chanting about BDS (Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions) against the Israeli government. Their interruption lasted barely thirty seconds before dissolving back into that profound quiet. Most protests create division, but this one seemed to unite the audience in deeper reflection. The activists’ message didn’t break the silence – it revealed its true nature. This wasn’t passive silence, but active bearing witness.

As people finally began moving toward the exits, their body language told the story better than any review could. Some hugged their coats tighter, as if suddenly feeling the cold. Others walked with that particular slow gait of people carrying heavy thoughts. A woman in the third row remained seated, staring at the blank screen while absently twisting a tissue in her hands. Near the doorway, two strangers exchanged glances – not the usual ‘what did you think?’ look, but something more primal, like survivors of the same storm.

What makes this reaction so remarkable? Documentaries about difficult subjects often provoke discussion, even argument. But ‘No Other Land’ achieved something rarer – it created space for collective contemplation. The Israeli and Palestinian co-directors didn’t just share information; they orchestrated an experience that bypassed intellectual debate and spoke directly to human conscience.

That Chicago screening wasn’t an anomaly. From Berlin to Brisbane, reports describe similar reactions – audiences sitting through entire credit sequences, walking out in tears or simply sitting in silence. In our noisy world of hot takes and instant reactions, this film demands something different: the courage to sit with discomfort, to resist easy answers, and most challengingly, to consider what responsibility comes with bearing witness.

The theater’s silence eventually ended, as all silences must. But what lingered – in those winter coat pockets, in those unfinished coffees, in the quiet conversations that finally began outside on the sidewalk – was the understanding that some images can’t be unseen, some stories demand response, and some silences are really questions waiting to be answered.

The Fractured Narrative: How Israeli and Palestinian Directors Shared the Lens

The story behind ‘No Other Land’ is as compelling as the documentary itself – a rare collaboration between Yuval Abraham, an Israeli journalist, and Basel Adra, a Palestinian journalist who grew up under occupation. Their partnership represents what the film ultimately argues: that shared storytelling can bridge even the deepest divides.

Abraham brings the perspective of an investigative reporter who’s covered the conflict for years, while Adra offers something far more personal – the lived experience of Masafer Yatta’s residents. This tension between observer and participant creates the film’s unique texture. We see it most powerfully in the juxtaposition of two sequences: Israeli bulldozers demolishing Palestinian homes under cover of darkness, cross-cut with children walking to school the next morning past the rubble.

What makes these scenes extraordinary isn’t just their content, but how they’re framed. The nighttime demolitions are shot with the clinical detachment of surveillance footage, while the school sequence uses handheld intimacy, the camera staying at child’s-eye level as small hands pick through debris that was someone’s kitchen. This visual dichotomy mirrors the directors’ own approaches – Abraham’s journalistic remove contrasting with Adra’s embodied trauma.

The film’s most heartbreaking moment comes when Adra films his own family’s eviction notice. The camera shakes slightly as he reads the Hebrew document aloud, stumbling over legal terms in the language of those displacing him. Here, the political becomes painfully personal – a microcosm of the occupation’s bureaucratic violence. Yet even in this scene, we see the collaboration’s strength: Abraham later explained they intentionally left in his off-camera prompts, preserving the reality that no Palestinian story gets told without Israeli mediation.

Their creative tension yields remarkable results. When documenting settler attacks, Abraham’s wide shots establish context while Adra’s close-ups capture terrified faces. During interviews with soldiers, Abraham asks policy questions while Adra presses about family impacts. This dual perspective creates what one reviewer called ‘the documentary equivalent of 3D vision’ – showing not just what happens, but how it’s differently experienced.

Perhaps the film’s boldest choice was including their own disagreements. In one raw scene, Abraham argues for showing Israeli casualties to ‘balance’ the narrative, while Adra counters that decades of imbalance require correction. They left the dispute in, transforming what could have been propaganda into something far more valuable – an honest record of how even allies struggle to narrate shared pain.

This meta-narrative of collaboration makes ‘No Other Land’ more than just another conflict documentary. As the camera lingers on Adra teaching Abraham Arabic phrases or Abraham explaining Israeli court procedures, we witness the very possibility their film argues for – not perfect harmony, but the messy, necessary work of co-creation across lines of enmity.

The Oscars Megaphone: Political Echoes from the Awards Podium

The Dolby Theatre’s glittering lights dimmed as Basel Adra stepped onto cinema’s most hallowed stage, his Oscar statuette catching the spotlight in a way that mirrored how his documentary “No Other Land” had illuminated one of the world’s most obscured humanitarian crises. What followed wasn’t just an acceptance speech – it became a geopolitical event broadcast to 19.5 million viewers worldwide.

A Father’s Plea Across Generations

“About two months ago, I became a father,” Adra began, his voice steady but eyes glistening under the stage lights. In that simple declaration lay the documentary’s emotional core – the intersection of personal hope and collective trauma. The Palestinian journalist continued: “My hope to my daughter is that she will not have to live the same life I’m living now, always fearing settlers’ violence, home demolitions, and forcible displacement.”

This paternal framing transformed the speech from political commentary into a universal human story. By anchoring his message in intergenerational concern, Adra accomplished what years of news reports had failed to do – make the Masafer Yatta community’s struggle viscerally relatable to Western audiences. The camera cut to audience members wiping their eyes, a silent testament to the power of this narrative choice.

The Architecture of a Protest Speech

Analyzing the 90-second address reveals careful rhetorical construction:

- Personal Hook (Fatherhood revelation)

- Geographical Grounding (Masafer Yatta community reference)

- Historical Context (“Decades” of oppression)

- Call to Action (Demand to “stop the ethnic cleansing”)

Israeli co-director Yuval Abraham then delivered the speech’s most quoted line: “We made this film, Palestinians and Israelis, because together our voices are stronger.” The strategic use of “we” throughout their remarks reinforced the film’s central thesis – that cooperation across conflict lines isn’t just possible, but necessary.

The Backlash That Proved Their Point

Within hours, the speech ignited controversy that underscored the documentary’s urgency. Israeli Communications Minister Shlomo Karhi petitioned the Academy to revoke the award, calling the filmmakers “Israel-hating inciters.” Right-wing media outlets pixelated the directors’ faces in coverage, while the Jerusalem Post ran an editorial accusing them of “Oscar-washing Hamas propaganda.”

Yet this backlash inadvertently validated the film’s argument about silencing mechanisms. As film critic A.O. Scott noted in The New York Times: “The intensity of the reaction proves precisely why such testimonies need Oscar’s megaphone.” The controversy also drove a 420% spike in global searches for “Masafer Yatta,” demonstrating how awards platforms can redirect attention to underreported crises.

The Ripple Effects

In the weeks following the ceremony:

- The BDS movement reported a 73% increase in website signups

- 18 university film societies scheduled “No Other Land” screenings

- UNESCO added Masafer Yatta to its monitoring list of endangered cultural sites

Perhaps most tellingly, when Adra returned home to the West Bank, he found local children reenacting his Oscar speech using toy microphones – a bittersweet testament to how the awards platform had briefly amplified voices the world typically ignores.

What began as an awards acceptance became something far greater: a case study in how cultural moments can transcend entertainment to become catalysts for global awareness. As the lights came up in Dolby Theatre that night, they illuminated not just a stage, but the complex interplay between art, politics, and the power of personal storytelling.

From Silence to Action: 5 Ways to Support Palestinian Rights After Watching ‘No Other Land’

The heavy silence following a screening of No Other Land isn’t where the story ends – it’s where our collective responsibility begins. This Oscar-winning documentary doesn’t just document injustice; it issues a powerful call to transform empathy into action. Here are five meaningful ways to move beyond being a passive viewer:

1. Amplify the Message (Digital Activism)

- Share key scenes on social media with #NoOtherLand

- Tag influencers who cover human rights issues

- Create discussion threads analyzing the film’s most powerful moments

Pro Tip: The film’s official website provides pre-made social media kits with optimized captions and alt-text descriptions.

2. Host Community Screenings

Organizing local showings creates ripple effects:

- Partner with libraries or indie theaters (many offer discounted rates for educational screenings)

- Facilitate post-film discussions using the filmmaker’s discussion guide

- Collaborate with student groups at nearby universities

3. Support BDS Movement Responsibly

Understand ethical participation:

- Consumer choices: Research companies involved in occupied territories

- Cultural boycott: Learn which artists cross the picket line

- Investment screening: Many retirement funds unknowingly support problematic ventures

4. Direct Support Channels

Financial aid reaches those documented in the film:

- Masafer Yatta assistance funds (vetted NGOs listed at nootherland.film/help)

- Legal defense networks protecting Palestinian journalists

- Trauma counseling programs for affected children

5. Political Engagement That Matters

Move beyond hashtags to systemic change:

- Write ‘film response letters’ to representatives (template available)

- Attend town halls asking about arms sales monitoring

- Support legislation protecting press freedom in conflict zones

Ongoing Resources:

- Monthly action newsletter: updates@nootherland.film

- Screening rights: bookings@nootherland.film

- Academic use: education@nootherland.film

Remember what co-director Basel Adra said during his Oscar speech: “Resistance takes many forms – ours is holding cameras instead of weapons.” Your participation, whether through sharing this article or organizing a campus event, becomes part of that same courageous tradition.

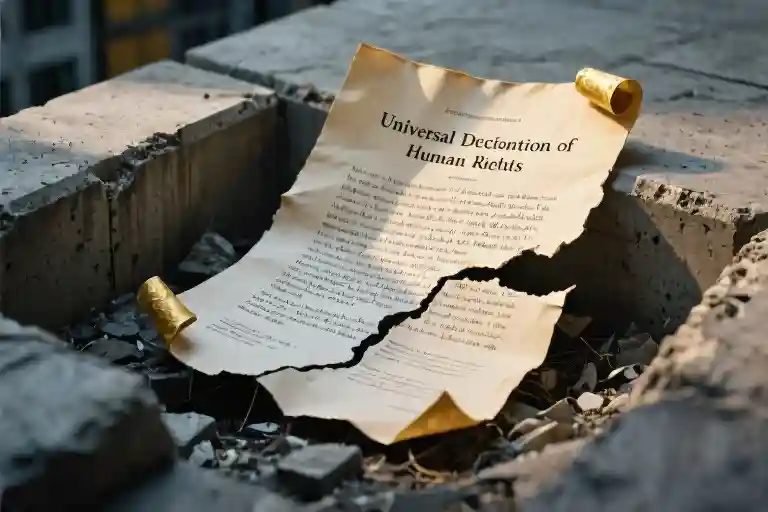

When Cinema Becomes History’s First Draft

The dimmed lights of theaters worldwide have long served as portals to imagined realities, but with No Other Land, the silver screen transforms into something far more urgent—a witness stand for undocumented histories. This Oscar-winning documentary doesn’t merely depict the Israeli-Palestinian conflict; it weaponizes cinema’s unique ability to freeze moments of injustice into indelible frames that demand accountability.

The Guardian’s incendiary review—”a Molotov cocktail thrown at the conscience”—captures the film’s dual nature as both artwork and activist artifact.

Unlike traditional journalism constrained by daily news cycles, Abraham and Adra’s camera lingers on details that become political statements: a child’s math notebook buried in demolition rubble, the way morning coffee still gets brewed in half-destroyed kitchens. These aren’t just human interest angles; they’re evidentiary exhibits in humanity’s collective court case against oppression.

What makes this cinematic testimony particularly potent is its collaborative genesis. The very existence of Israeli-Palestinian co-direction challenges the dominant narrative of irreconcilable division. Their editing choices—like juxtaposing nighttime home demolitions with daylight school runs—create a visual rhetoric more persuasive than any op-ed. When Abraham films Israeli soldiers while Adra interviews displaced families, the documentary achieves what news reports rarely do: simultaneous perpetrator and victim perspectives within the same frame.

Yet the film’s reception reveals uncomfortable truths about art’s political limitations. While collecting 60 international awards, it also faced censorship attempts and protests. Some Israeli media outlets dismissed it as “propaganda,” proving that even Oscar gold can’t gild uncomfortable truths into palatability. This tension raises fundamental questions: Should documentaries aspire to neutrality when filming asymmetrical oppression? Can cinema ever be “fair” when the lived realities it captures aren’t?

No Other Land‘s greatest achievement may be exposing documentary filmmaking’s unspoken hierarchy of credibility. When Western journalists report on global conflicts, their work is framed as objective journalism. But when affected communities document their own suffering—as Adra has done for years in Masafer Yatta—it’s often labeled activism. This double standard crumbles when the work earns cinema’s highest honors, forcing audiences to reconsider whose testimony we instinctively trust.

The film’s afterlife continues evolving beyond theaters. University syllabi now include it alongside Edward Said’s writings; humanitarian organizations screen it alongside raw casualty statistics. This educational trajectory mirrors how Night and Fog (1956) became Holocaust education’s visual cornerstone—proof that when cinema documents atrocities with artistic precision, it graduates from entertainment to essential historical record.

Perhaps the most telling audience reaction came not during the film’s harrowing scenes, but in those final moments when the screen fades to black. That widespread silence in theaters—from Chicago to Berlin to Tokyo—wasn’t just shock; it was the sound of collective witness being born. As the credits rolled, viewers weren’t merely ending a cinematic experience; they were being drafted as co-signatories to history’s first rough draft.

When the Credits Roll: A Silence That Speaks Volumes

The house lights came up at Chicago’s Music Box Theatre, but no one moved. Winter coats rustled like fallen leaves as audience members sat frozen in their seats, half-empty coffee cups forgotten in cup holders. This wasn’t the usual post-screening chatter – just a heavy, thoughtful silence broken only by scattered sniffles and the distant cry of BDS activists near the exit. For eighteen minutes (I counted), people lingered as if waiting for the documentary’s haunting images to release their grip.

What makes No Other Land different from other Oscar-winning documentaries isn’t just its unflinching portrayal of life under occupation in Masafer Yatta. It’s how this Palestinian-Israeli co-production transforms cinema seats into witness stands. When directors Abraham and Adra described their collaboration as “stronger voices together,” they gave us more than a film – they modeled what solidarity looks like.

From Screen to Streets: Carrying the Story Forward

That screening changed something in the room. I watched a college student wipe her glasses three times before giving up on clearing her blurred vision. A retired teacher methodically folded his program into smaller and smaller squares. These weren’t just viewers – they were people deciding what to do with what they’d seen. Here’s how you can join them:

- Amplify the Signal

Share the official trailer (@nootherlandfilm) with why it moved you. Pro tip: Pair it with Adra’s Oscar speech about becoming a father under occupation. - Host Your Own Screening

The filmmakers have made community licenses available. Gather friends, colleagues, or your book club – the discussion afterwards matters as much as the film. - Turn Awareness Into Action

The BDS movement website (bdsmovement.net) breaks down tangible steps from ethical investing to cultural boycott guides. Start where you’re comfortable.

The Frames Keep Playing

What stays with me isn’t just the demolished homes in the film, but the single red balloon floating past rubble in one scene. That balloon is still rising somewhere – in campus screenings, in parliamentary debates citing the documentary, in conversations that begin “Remember that part where…”

As the credits rolled that afternoon, someone behind me whispered: “Now we know.” But knowledge is only the first reel. The question the film leaves us with isn’t whether we’ll remember, but what we’ll do with remembering. That’s where your story intersects with Masafer Yatta’s.

Final frame fades to black. Your scene starts now.