The human impulse to create symbols runs deeper than we often assume. Sigmund Freud once observed that symbolism isn’t our modern invention, but rather “a universal age-old activity of the human imagination.” This truth finds startling confirmation in the cool darkness of La Roche-Cotard cave, where finger marks on ancient walls whisper secrets about our misunderstood cousins – the Neanderthals.

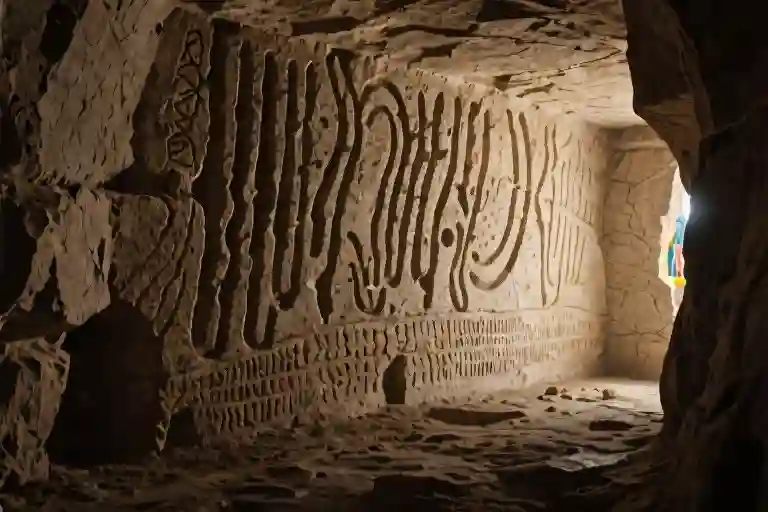

For decades, we’ve pictured Neanderthals as primitive brutes, their thick brows shadowing minds incapable of abstract thought. The cave walls in France’s Loire Valley tell a different story. There, organized patterns of finger flutings stretch across stone surfaces, patterns so deliberate they couldn’t be accidental scrapings. When researchers first noticed these markings in the 1970s, they seemed too sophisticated to attribute to anyone but Homo sapiens.

Modern technology has shattered that assumption. Between 2016 and 2023, archaeologists meticulously documented these Paleolithic engravings using 3D modeling, comparing them with known examples of cave art across Europe. The sediment layers sealing these creations dated between 57,000 and 75,000 years old – millennia before our species arrived in the region. Surrounding stone tools bore the unmistakable signature of Neanderthal craftsmanship.

This discovery does more than push back the timeline of symbolic expression. It forces us to reconsider what separates “us” from “them.” Those finger marks represent more than idle doodles; they’re evidence of minds capable of translating thought into lasting physical form. The cave becomes a gallery where we glimpse Neanderthal consciousness reaching beyond survival needs to touch something we recognize as artistic impulse.

Perhaps we’ve been asking the wrong question all along. Instead of wondering when humans became capable of art, we might consider whether art-making belongs exclusively to humans at all. The walls of La Roche-Cotard suggest symbolic thinking emerged earlier and more universally than our anthropocentric narratives allowed. As sediment layers accumulate over scientific paradigms, this French cave offers not just new data, but a new lens through which to view our extinct relatives – not as crude precursors, but as fellow travelers in the long journey of the imagining mind.

The Cave That Whispered Secrets

The walls of La Roche-Cotard cave have been keeping quiet for millennia. Not the dramatic silence of emptiness, but that peculiar quiet of something waiting to be understood. When researchers first noticed those curious markings in the 1970s – delicate grooves tracing across the stone like frozen fingerprints – they sensed these weren’t random scratches. But proving intentionality in prehistoric markings requires more than intuition.

What emerged from decades of study was a revelation written in stone and sediment. The cave’s finger flutings – those parallel lines carved into soft limestone – formed distinct panels with recognizable patterns. Some resembled rudimentary lattices, others created abstract shapes that modern eyes might interpret as animals or symbols. Their arrangement suggested deliberation, each mark placed with purpose rather than accident.

The dating evidence sealed the case. Layers of sediment that had gently entombed these markings held their secret until modern science could read them. When analyzed, they revealed these markings were made between 57,000 and 75,000 years ago – a time when Neanderthals roamed Europe alone, long before Homo sapiens arrived in the region. The cave’s accompanying stone tools, unmistakably Neanderthal in craftsmanship, completed the picture.

There’s something profoundly moving about these markings. Not just their age, though contemplating 75,000 years does give one pause. It’s their quiet persistence – how they survived ice ages and climate shifts, outlasting their creators by tens of millennia. They weren’t meant for us, these ancient messages. Yet here we are, squinting at 3D models trying to understand what moved someone to trace fingers across damp stone in the flickering firelight of a world since lost.

What emerges from the sediment layers and tool fragments is a narrative far richer than the ‘brute Neanderthal’ stereotype. These markings suggest minds capable of abstraction, of seeing beyond immediate survival. Whether ritual, storytelling, or simply the Pleistocene equivalent of doodling, they represent a cognitive leap we once thought unique to our own species. The cave’s walls, it turns out, had more to say than we ever imagined.

The Digital Archaeology Revolution

The cave walls at La Roche-Cotard hold secrets that remained locked for millennia—until modern technology gave us the keys. What makes this discovery extraordinary isn’t just the age of these markings, but how we’ve come to understand them. Traditional archaeology could tell us about stone tools and bone fragments, but decoding intentional artistry required something more.

Reading Prehistoric Fingerprints

Researchers didn’t just photograph those curious lines on the cave walls—they built them anew in digital space. Using structured light scanners and photogrammetry, each groove and ridge became data points in a three-dimensional map. This wasn’t about creating pretty visuals; the 3D models revealed details invisible to the naked eye. The depth profiles showed consistent pressure patterns, the angles suggested deliberate hand positioning, and the sequences demonstrated compositional logic.

The real breakthrough came when comparing these digital reconstructions with known cave art techniques. Modern human creations from later periods show similar structural principles—planned spacing, rhythmic repetition, and what appears to be symbolic grouping. The Neanderthal markings weren’t random scratches, but followed visual rules we recognize as artistic intention.

Time Capsules in Sediment

Dating cave art is notoriously difficult—you can’t carbon-date stone. Here, scientists turned to the very material that preserved these markings: the sediment that gradually sealed the cave. Using optically stimulated luminescence (OSL), they measured when quartz grains in the clay layers last saw sunlight. The results created a chronological sandwich—the art had to exist before the oldest sediment layer covering it (75,000 years ago) but after the youngest layer beneath it (57,000 years ago).

This dating method relies on physics rather than assumptions. When buried, minerals accumulate radiation damage at predictable rates. The technical process involves exposing samples to precise light wavelengths and measuring emitted photons—a far cry from Indiana Jones-style archaeology, but arguably more thrilling in what it reveals about our ancestors.

The Human Comparison

Some skeptics argued these could be accidental marks until the team compared them with undisputed Homo sapiens cave art. The differences became as telling as the similarities. Later human artworks often depict identifiable animals or symbols, while the Neanderthal creations show abstract patterns—parallel lines, zigzags, and clustered dots. This distinction matters less than what it shares: the cognitive capacity for symbolic representation.

Interestingly, the physical creation methods overlapped significantly. Both species used fingers to make marks in soft surfaces, both returned to certain panels repeatedly, and both selected specific wall areas for their compositions. The main divergence appears in cultural evolution—where sapiens developed increasingly complex representations, Neanderthal artistic tradition seems to have remained more abstract.

What emerges from this digital reconstruction isn’t just a technical achievement, but a philosophical shift. We’re no longer interpreting ancient minds through the filter of their tools or bones, but through the direct products of their creative consciousness. The walls at La Roche-Cotard don’t just show us what Neanderthals could make—they show us how they thought.

Rewriting Cognitive Evolution

The stone tools found alongside the finger markings in La Roche-Cotard cave tell a silent but compelling story. These weren’t crude implements randomly chipped from rock – the distinctive Mousterian points and scrapers show deliberate craftsmanship that persisted across generations. What’s remarkable isn’t just their presence, but their contextual relationship to the wall markings. The same hands that shaped flint into precise cutting edges also traced deliberate patterns on cave walls.

Neanderthal brain capacity actually exceeded that of modern humans by about 100 cubic centimeters on average. This anatomical fact often gets buried under popular depictions of hunched brutes. Their enlarged occipital lobes suggest advanced visual processing, while endocast studies reveal developed Broca’s areas – the speech centers of the brain. When you hold a Neanderthal tool in one hand and examine their cave markings with the other, the cognitive connection becomes undeniable. These weren’t accidental doodles, but expressions emerging from minds capable of symbolic thought.

The academic world has been quietly dismantling the “behavioral modernity” checklist that once rigidly separated humans from other hominins. For decades, archaeologists used criteria like ritual burial, ornamentation, and cave art as exclusive markers of human cognition. The La Roche-Cotard findings join mounting evidence from sites across Europe – the eagle talon necklaces in Croatia, the mineral pigments in Spain – that force us to confront an uncomfortable truth. Our definitions of art and symbolism have been hopelessly anthropocentric.

Three key debates now dominate paleoanthropology circles:

- Whether we’ve underestimated parallel cognitive evolution in Neanderthals

- How to redefine “modern behavior” without human exceptionalism

- What truly caused Neanderthal extinction if they shared our creative capacities

The most profound implication isn’t that Neanderthals could create art, but that art itself may be an inevitable byproduct of advanced cognition – a cognitive tool that emerges whenever a brain reaches certain complexity, regardless of species. This challenges the very framework we use to understand human uniqueness. Perhaps symbolism isn’t something we invented, but something we discovered – a latent capacity waiting to emerge in any mind complex enough to grasp it.

When Symbols Ignited Across Europe

The discovery at La Roche-Cotard doesn’t stand alone as evidence of Neanderthal creativity. Across Europe, scattered fragments tell a broader story of symbolic expression that predates Homo sapiens’ dominance. These findings collectively challenge the notion that symbolic thinking emerged exclusively with modern humans.

In Iberia’s mountainous terrain, archaeologists uncovered processed red ochre at Cueva de los Aviones. This mineral pigment, carefully collected and prepared, suggests more than utilitarian use. The presence of perforated seashells stained with ochre hints at bodily adornment – perhaps Europe’s first jewelry. Unlike random collections, these shells show consistent hole placement, indicating deliberate stringing for necklaces or garments.

Central Europe yields equally compelling evidence. At Krapina Cave in Croatia, researchers found eight white-tailed eagle talons bearing cut marks and polish. Arranged as a necklace or rattle, these talons represent the oldest known avian jewelry at 130,000 years. The selection of eagle claws carries particular significance – these apex predators would have been challenging to hunt, suggesting the talons held special meaning beyond decoration.

What survival advantage could such behaviors provide? Evolutionary anthropologists propose several theories. Symbolic artifacts may have strengthened group identity, much like modern team insignia. Pigment use could have signaled health or status, while jewelry might have denoted kinship ties. In harsh Pleistocene environments, these markers could facilitate cooperation between scattered bands.

The timing of these discoveries coincides with climatic upheavals during Marine Isotope Stage 5. As glaciers advanced and retreated, Neanderthal groups faced mounting ecological pressures. Their cultural responses – pigment use, ornamentation, and eventually cave marking – may represent cognitive adaptations to these challenges. Rather than luxury behaviors, these symbolic practices might have been crucial survival strategies.

Recent genetic findings add another dimension. The discovery of the FOXP2 gene variant in Neanderthals, associated with language development in humans, suggests they possessed neurological capacity for complex communication. When combined with archaeological evidence, a picture emerges of communities sharing knowledge through symbols during critical climate fluctuations.

These scattered artifacts form a constellation of evidence pointing toward Neanderthal cultural sophistication. From Iberia’s ochre-stained shells to Croatia’s eagle talons and France’s finger-fluted caves, a pattern emerges of ancient minds seeking to make their mark – literally and metaphorically – upon the world. The implications ripple beyond archaeology, inviting us to reconsider the very nature of human uniqueness.

As research continues, each new discovery adds brushstrokes to our evolving understanding of cognitive history. The emerging portrait shows multiple human species engaging in symbolic behavior across millennia, with Neanderthals contributing distinct chapters to this shared story of the mind’s development.

Rethinking What Makes Us Human

The discovery at La Roche-Cotard cave forces us to confront uncomfortable questions about human exceptionalism. Those deliberate finger markings, preserved through 75 millennia, whisper across time that perhaps we’ve drawn the boundaries of art and symbolism too narrowly.

Neanderthal artistic expression changes the evolutionary narrative in fundamental ways. Their cave markings predate the famous Lascaux paintings by tens of thousands of years, suggesting symbolic thought didn’t emerge full-blown with Homo sapiens but developed gradually across human species. The implications ripple through anthropology, cognitive science, and even philosophy – if our extinct cousins could leave intentional marks, where exactly does the threshold of ‘humanity’ begin?

This challenges the persistent myth of Neanderthals as grunting brutes. The same hands that crafted sophisticated Mousterian tools also traced patterns on cave walls, revealing a cognitive landscape richer than we imagined. Their art may lack the figurative brilliance of later cave paintings, but intention matters more than technical mastery when assessing symbolic capacity. Those parallel lines and deliberate curves represent something profound – the birth of abstraction.

The real revelation isn’t that Neanderthals could make marks, but that they chose to. In the perpetual dampness of limestone caves, someone repeatedly returned to certain walls, pressing fingers into soft surfaces with apparent purpose. This wasn’t utilitarian tool-making but something more enigmatic – perhaps ritual, perhaps communication, perhaps simply the Pleistocene equivalent of ‘I was here.’

What does this mean for our understanding of art’s origins? The traditional narrative of creative explosion around 40,000 years ago now appears oversimplified. Symbolic expression seems to have deeper roots, emerging piecemeal across different human species. Maybe art isn’t the exclusive domain of anatomically modern humans but a capacity that flickered intermittently in various forms across our evolutionary cousins.

The most humbling realization? We may never fully comprehend what those markings meant to their creators. The gap between their lived experience and our interpretation remains unbridgeable, reminding us that the past is ultimately a foreign country. Yet the very existence of these ancient symbols suggests shared ground – a common impulse to make meaning visible, to leave traces that outlast flesh and bone.

Perhaps the question isn’t whether Neanderthals could create art, but why we ever doubted they might.