There’s something deeply comforting about returning home after a long trip and sinking into your own bed. The familiar dip of the mattress, the way the pillow conforms to your head just right—these small comforts signal true relaxation. We spend nearly a third of our lives in beds, forming attachments stronger than we often realize. But have you ever considered that this intimate object of comfort might also serve as your final resting place?

The connection between beds and eternal rest isn’t as far-fetched as it might seem. Across cultures, death has frequently been described as ‘eternal sleep’—a metaphor that medieval Europeans took quite literally. Archaeological evidence reveals an unusual burial practice where individuals were interred with their beds, a tradition now being reevaluated by researchers like Dr. Astrid Noterman.

These bed burials, found scattered across Germany, England, and Scandinavia, represent more than just peculiar funeral customs. They offer windows into how medieval societies viewed both sleep and death, blending practical concerns with spiritual beliefs. For decades overshadowed by more glamorous grave goods, these burial beds are finally receiving scholarly attention for what they truly were—complex social markers and perhaps the ultimate expression of finding comfort in the familiar.

What makes this practice particularly fascinating isn’t just its existence, but how it mirrors our modern relationship with beds. The same sense of security that makes us sigh with relief when collapsing into our own sheets after travel may have motivated medieval people to choose beds as companions for their final journey. As we’ll see, these weren’t random sleeping surfaces but carefully selected objects carrying layers of meaning about status, identity, and humanity’s universal longing for rest—both temporary and permanent.

The Bed and Eternal Rest: A Metaphor Across Millennia

There’s something profoundly comforting about returning to your own bed after time away. The familiar dip of the mattress, the way the pillow conforms to your head – these small details create a sense of security that no luxury hotel can replicate. This deep connection we feel with our sleeping spaces isn’t just a modern phenomenon. Across cultures and centuries, beds have held symbolic weight far beyond their practical function, often serving as bridges between waking life and what comes after.

Ancient Egyptians understood this connection better than most. Their funerary art frequently depicts the deceased reclining on beds, with the famous ‘death beds’ found in tombs serving as both practical burial items and powerful symbols. These weren’t mere sleeping arrangements but vessels for the soul’s journey – the original box springs for eternal rest. The British Museum holds a particularly striking example: a wooden bed from Thebes dating to around 1550 BCE, its curved headrest designed to cradle not just a sleeping head but one transitioning to the afterlife.

The Romans continued this tradition with their lectus funebris, the funeral bier that doubled as a bed for the deceased during mourning rituals. What began as a practical surface for displaying the body took on deeper meaning, becoming a symbolic final resting place before cremation or burial. Archaeological finds in Pompeii reveal how these beds were sometimes interred with their owners, blurring the line between temporary resting place and permanent tomb.

Northern European cultures developed their own variations on this theme. The Oseberg ship burial in Norway contained not just a Viking vessel but an ornate bed, its carved posts suggesting the deceased’s high status. Here, the bed served multiple purposes: a comfortable resting place for the journey to Valhalla, a status marker, and perhaps even a practical consideration for whatever existence might follow death.

This persistent connection between beds and eternal rest appears in our language too. We speak of the ‘sleep of death’ and mark graves with ‘Rest in Peace’ – phrases that reveal how deeply the metaphor has permeated our collective consciousness. The medieval bed burials studied by Dr. Noterman didn’t emerge from nowhere; they represent the physical manifestation of an idea that has comforted humanity for millennia: that death might simply be a longer, deeper version of the sleep we experience every night.

What’s particularly fascinating is how these burial practices reflect cultural attitudes toward both sleep and death. Egyptian death beds often included magical texts to protect the sleeper, while Viking burials might feature practical items like combs and bowls – as if preparing for morning ablutions after the long sleep. The bed becomes more than furniture; it’s a threshold object, existing between states, between worlds, between what we know and what we can only imagine.

Dust and Down: Uncovering Medieval Bed Burials

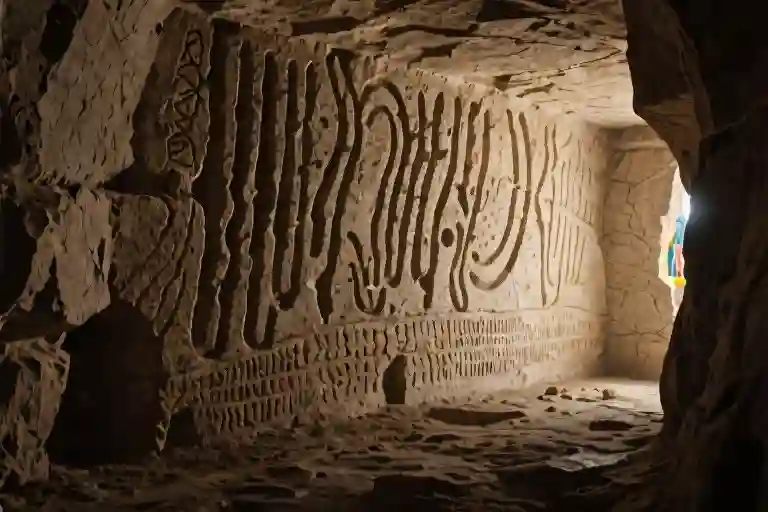

Archaeological sites across Northern Europe hide peculiar graves that challenge our modern funeral expectations. These aren’t your typical burial plots with simple coffins or shrouds, but rather carefully arranged final resting places containing complete beds – some with feather mattresses still intact, others with ornate carvings now softened by centuries of soil.

The practice left its traces primarily in three regions: the coastal areas of Scandinavia where Viking traders slept their last sleep atop ship-like bed frames, the Saxon settlements of England with their oak plank constructions, and the Germanic territories where iron fittings outlasted the wooden frames they once supported. A cluster near Trier suggests this might have been an elite funerary fashion spreading along trade routes.

What’s surprising isn’t that these burials existed, but how little attention they’ve received compared to other grave goods. Three main reasons emerge from Dr. Noterman’s research. First, the beds themselves often decay, leaving only metal fittings that early archaeologists catalogued as ‘miscellaneous ironwork’. Second, the spectacular jewelry or weapons buried with the deceased naturally drew more interest than what appeared to be simple furniture. Third, and perhaps most telling, modern assumptions projected backwards led scholars to interpret these as ‘couches for the afterlife banquet’ rather than actual sleeping arrangements.

Yet the beds tell stories the glittering artifacts cannot. The wear patterns on a bedpost from Suffolk show decades of use before burial, suggesting a beloved household item rather than funeral-specific furniture. Soil stains on a Norwegian burial indicate the deceased was laid to rest with their usual bedding – the medieval equivalent of taking your favorite pillow to the grave. In Schleswig, differential preservation revealed how straw-filled mattresses for commoners contrasted with wool-stuffed ones for the elite, a social hierarchy preserved in bedding materials.

These silent witnesses complicate our understanding of medieval attitudes toward death. While swords and brooches might indicate status, the choice to include a bed speaks to more intimate concerns – the comfort of familiar surroundings, the continuation of daily rituals, perhaps even the hope that death truly was just an extended sleep. As we examine these archaeological sites, we’re not just cataloging burial practices, but encountering the medieval equivalent of that universal longing we still feel when traveling: the deep human desire to finally, restfully, come home.

The Social Code in Bed Burials: Dr. Noterman’s Revelations

Archaeologists often find social hierarchies written in unexpected places—none more intimate than the beds where medieval Europeans took their final rest. Dr. Astrid Noterman’s work reveals how these burial beds functioned as silent heralds of status, their materials and craftsmanship whispering secrets across centuries.

In a 7th-century grave from Kent, England, the oak bed frame of a noblewoman still held traces of its original carvings—interlacing patterns that mirrored the jewelry placed around her skeleton. The iron nails showed minimal corrosion, suggesting they’d been forged with uncommon skill. This wasn’t just furniture; it was a final proclamation. “The bed legs alone would have required three craftsmen working for a month,” Noterman notes in her journal article, pointing to the economic calculus behind funerary displays.

Contrast this with a contemporaneous burial in rural Germany, where pollen analysis revealed a mattress stuffed with barley straw. No frame survived—just faint soil stains outlining where simple wooden planks once lay. Yet even here, hierarchy persisted: the straw contained unusually high concentrations of chamomile and lavender, plants associated with healing. “Someone took care to gather these,” Noterman observes. “In death as in life, comfort had degrees.”

Three key distinctions emerge from these bed burials:

- Material Language: Noble beds used hardwoods (oak, beech) with joinery techniques, while commoners’ beds relied on softwoods (pine, fir) nailed together

- Textile Markers: High-status burials often included woven bedhangings, with some preserving traces of dyes like madder red—a luxury import

- Spatial Claims: Elites were buried with full-size beds (avg. 2m length), whereas lower-status graves show shortened frames (1.5m or less)

What fascinates Noterman isn’t just the inequality, but the shared vocabulary. “Whether straw or silk, everyone understood beds symbolized transition,” she writes. The very act of including a bed—regardless of quality—suggested a cultural consensus about death’s nature. Modern sleep researchers might recognize this impulse: we still describe grief as “learning to sleep in a new world.”

Curiously, bed burials skew female by a 3:2 ratio in Noterman’s dataset. One theory connects this to textile tools found in many women’s graves—distaffs and loom weights resting atop bed frames like final projects. “Perhaps,” the archaeologist muses, “these beds represented domestic spheres women controlled even in death.”

The most poignant find came from a Swedish Viking-age burial, where a child’s small bed frame held not weapons or jewels, but a worn wooden horse. The analysis showed tooth marks on its legs. In this context, the bed became more than status symbol—it was a portrait of interrupted childhood, a parent’s last attempt to furnish comfort beyond the grave.

Sleeping Through the Ages: From Medieval Beds to Modern Rest

There’s something profoundly comforting about slipping between familiar sheets after time away. The way the mattress conforms to your body’s memory, the particular scent of your pillowcase – these details create a sensory homecoming. But this intimate relationship with our sleeping spaces extends far beyond temporary absences. For medieval Europeans, the connection between beds and eternal rest wasn’t metaphorical but literal, as evidenced by the practice of bed burials. Today, as we reconsider traditional funeral practices and deepen our understanding of sleep science, we’re rediscovering the enduring human need to make peace with our final repose.

Contemporary funeral reformers are challenging conventional burial norms much like medieval communities developed their own distinctive practices. Modern advocates for green burials emphasize returning to the earth without chemical preservatives, echoing the organic simplicity of early bed burials where wooden frames decomposed naturally. The resurgence of home funerals and personalized death care reflects our growing desire to make death familiar rather than frightening – not unlike how medieval people surrounded themselves with household objects for their eternal sleep.

Sleep laboratories have uncovered fascinating data about environmental familiarity and rest quality. Studies show people experience deeper sleep cycles when surrounded by personally significant textures and scents. This neurological preference might explain why medieval communities placed such importance on burying their dead with beds – the ultimate familiar object for perpetual slumber. The same brain regions that light up when we recognize our own pillows today may have motivated ancient mourners to ensure their loved ones’ comfort in the afterlife.

What emerges across centuries is a consistent human impulse: we seek to transform the unknown into something recognizable. Whether through seventh-century bed burials or twenty-first-century memory quilts made from a deceased loved one’s clothing, we use domestic objects to domesticate death itself. The medieval woman buried with her carved oak bed frame and the modern hospice patient clutching a childhood blanket share more in common than we might initially assume – both are asserting control over life’s most uncontrollable transition through tactile comfort.

As sleep scientists continue mapping the relationship between environment and restfulness, their findings inadvertently validate ancient intuitions about death preparation. The warm weight of wool blankets that helps insomnia patients today mirrors the careful textile selections found in Viking bed burials. Perhaps our ancestors understood something fundamental about human psychology that we’re only now quantifying with brain scans and sleep trackers – that whether facing a night’s sleep or eternal rest, we all deserve the comfort of feeling at home.

The Modern Echo of Eternal Rest

We end where we began—with the simple human longing to return to one’s own bed. That primal comfort we seek after travel now carries an unexpected historical shadow. The medieval bed burials we’ve explored weren’t about morbidity, but about completing life’s most fundamental cycle: we rise from sleep, we return to sleep. Forever.

Contemporary funeral practices have largely abandoned physical beds, yet the symbolism persists. The rise of ‘green burials’ using biodegradable materials mirrors the medieval preference for simple wooden bed frames over stone sarcophagi. Modern casket designs increasingly incorporate pillow-like headrests, unconsciously recreating the sleeping posture of those ancient bed burials.

A sleep technologist I spoke with observed an intriguing parallel: “The way people now customize mattresses for optimal rest—memory foam layers, cooling gels—isn’t so different from how medieval nobles adorned their funeral beds with carvings and textiles. Both are attempts to perfect repose.”

This leaves us with an uncomfortable but fascinating question: If given the choice, would you want to be buried with your bed? Not the concept, but your actual mattress with its permanent dent from years of sleeping in the same position, the faint stain from that time you spilled tea while reading. There’s something profoundly human about considering what objects truly deserve to accompany us into eternity.

Perhaps the greatest lesson from these overlooked bed burials is that death rituals always reflect living habits. The Vikings buried warriors with ships, nomads with their tents, and medieval Europeans with their beds. Today we might ask—what objects define our daily existence so completely that their absence would make eternity feel unfamiliar? For many, the answer still lies in that quiet rectangle where we spend a third of our lives.”

Additional perspective from a sleep product designer: “We’ve measured how people subconsciously create ‘nesting’ patterns in their bedding. That territorial imprinting is why hotel beds never feel quite right—and perhaps why the dead insisted on taking theirs along.”