In April 1934, F. Scott Fitzgerald mailed the manuscript of Tender Is the Night to his friend Ernest Hemingway with a note that simply read: “Be brutally honest.” What came back wasn’t just criticism—it was a masterclass in writing that still crackles with relevance nearly a century later. Hemingway’s reply, preserved in Selected Letters 1917–1961, begins with a sentence that stings like whiskey on a cut: “Ninety percent of what you’ve written is pure crap.”

Most writing advice glosses over this fundamental truth. We’re fed myths of effortless genius—Shakespeare conjuring sonnets in single sittings, Kerouac typing On the Road in three weeks on a benzedrine haze. But Hemingway, the man who rewrote the ending to A Farewell to Arms thirty-nine times, knew better. His letter outlines six survival strategies for writers that have nothing to do with talent and everything to do with showing up at the desk, day after day, willing to produce those ninety pages of garbage for every one that sings.

What makes these insights extraordinary isn’t just their source—it’s how they dismantle every romantic illusion about creation. This isn’t a letter about inspiration; it’s about excavation. Hemingway treats writing as hard labor, equal parts mining (digging through worthless rock to find specks of gold) and butchery (carving away fat until only essential muscle remains). He addresses Fitzgerald’s specific struggles—his financial woes, his wife’s schizophrenia, his alcoholism—but the solutions transcend their era. When he warns against “monkeying with characters’ pasts,” he’s outlining the ethics of biographical fiction. When he insists on writing “truly, no matter who it hurts,” he’s drafting the manifesto for autofiction decades before the term existed.

The real surprise? How contemporary the advice feels. Replace “listening to the answers to your own questions” with algorithm-driven social media echo chambers, and Hemingway’s warning about creative dehydration could’ve been written yesterday. His insistence on processing emotion “like a scientist” anticipates the current neuroscience of expressive writing. Even his blunt “we are only writers” mantra mirrors today’s focus on creative identity over transient success.

This isn’t just literary history—it’s an operating manual for anyone who’s ever stared at a blank page wondering why their words feel dead. Hemingway’s solutions are startlingly simple: write badly until you don’t, steal from life but never lie, and above all, keep working when every cell screams to quit. As we unpack each of his six lessons, you’ll notice they share one thread—writing isn’t something that happens to you; it’s something you do, relentlessly, through doubt and disaster. That’s why Fitzgerald needed this letter in 1934, and why we still need it today.

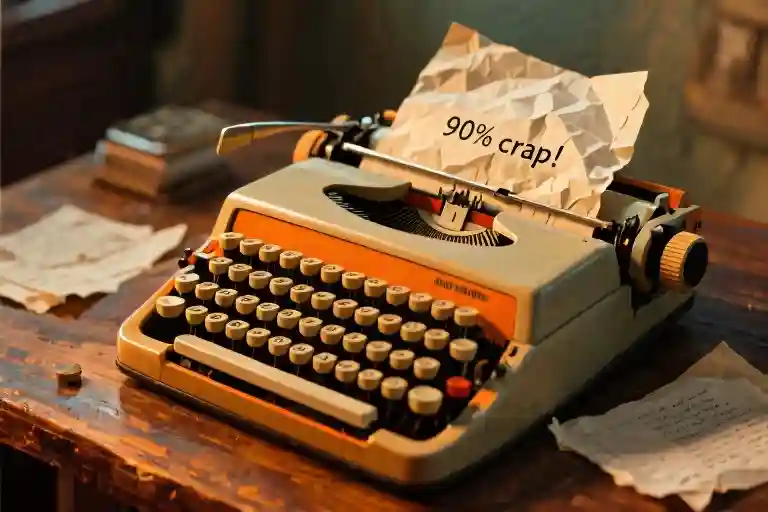

The 90% Crap Rule: Why Literary Masters Need Wastebaskets Too

Ernest Hemingway’s typewriter must have collected more crumpled paper than finished manuscripts. When F. Scott Fitzgerald sought his friend’s opinion on Tender Is the Night, Hemingway didn’t offer polite encouragement. His typewritten response contained a truth every writer needs tattooed on their writing hand: “I write one page of masterpiece to ninety pages of shit.”

This 1:90 ratio isn’t failure—it’s the natural law of creative work. Consider ceramic artists who expect 30% of their pots to crack in the kiln, or pharmaceutical researchers who test thousands of compounds for one viable drug. Writing operates by the same principles of necessary waste. J.K. Rowling’s twelve publisher rejections for Harry Potter weren’t setbacks; they were the required ninety pages.

Modern psychology explains why this ratio terrifies us. Perfectionism triggers what researchers call “evaluation apprehension”—we freeze when imagining others judging our imperfect drafts. A 2020 Stanford study found writers who embraced “strategic imperfection” completed 47% more projects than their perfectionist peers. The blank page doesn’t fear your brilliance; it fears your willingness to fill it with mediocre words.

Try this today: Write 500 words with strict rules—no deleting, no editing, no rereading. Save the document as “April 30 – Protected Draft.” Tomorrow, mine it for one usable sentence (your 10%), then repeat. After seven days, you’ll have seven golden nuggets swimming in 3,150 words of what Hemingway would proudly call “shit.”

What makes this advice radical isn’t the acceptance of bad writing, but the celebration of it. Those ninety pages aren’t obstacles—they’re the raw materials from which masterpieces get distilled. Every morning, Hemingway measured his progress by weight rather than quality, counting written pages like a miner tallying buckets of ore. Your trash bin should fill faster than your polished documents folder.

Virginia Woolf’s diaries reveal she wrote 300,000 discarded words for every published novel. John Steinbeck kept a journal while writing The Grapes of Wrath where he routinely cursed his “awful, embarrassing” daily output. What separated them from aspiring writers wasn’t talent—it was their willingness to protect their worst work from the delete key.

Your next terrible sentence might be the bridge to something extraordinary. As Neil Gaiman advises: “Write your story as it needs to be written. Fix it later.” The 90% protects the 10% like scaffolding around a cathedral—ugly, temporary, and absolutely essential.

Character Homicide: When You Tamper with DNA

Hemingway’s accusation cuts like a butcher’s knife: “You gave them parents they never had.” This wasn’t just critique—it was an indictment of Fitzgerald’s fundamental breach of writer’s ethics. The problem wasn’t that Fitzgerald borrowed from life, but that he grafted foreign limbs onto living souls.

Modern literature provides cautionary tales. When Woody Allen’s Midnight in Paris featured thinly-veiled versions of Hemingway and Fitzgerald themselves, it danced on the edge of legal peril. The estates of literary figures hold surprising power over their depictions, a reality every writer mining real-life material must confront.

The Three-Degree Distillation Method

For writers determined to use real people as springboards, consider this safety protocol:

- Name Alchemy: Change more than just first letters. Transform ‘Margaret Thatcher’ into ‘Martha Thimbleton’—the ear shouldn’t recognize the echo.

- Career Transmutation: If your inspiration is a neurosurgeon, make them a pastry chef. Shared skills (precision, steady hands) create plausibility without direct mapping.

- Temporal Displacement: Drop your 21st century tech CEO into 1920s bootlegging operations. Contextual dissonance protects while revealing universal truths.

Virginia Woolf’s Mrs. Dalloway demonstrates this beautifully. While drawing from aristocratic circles she knew intimately, she constructed characters that stood as original creations—inspired by life, but not chained to it. The mark of successful fictionalization isn’t how well you disguise, but how thoroughly you reimagine.

This isn’t merely legal protection—it’s creative liberation. When we stop trying to replicate people and instead extract their essential sparks, we paradoxically honor them better than any factual reporting could. The surgeon’s intensity becomes the chef’s perfectionism; the politician’s charisma transforms into a conductor’s magnetism. What remains true isn’t the surface details, but the human core.

Hemingway’s fury at Fitzgerald’s halfway measures reveals a deeper truth: bad fiction isn’t that which diverges from reality, but that which can’t commit to being either truth or invention. Your characters deserve the dignity of being wholly themselves—whether drawn from life or born from pure imagination.

Blood Typing Your Prose: When Truth Needs a Tourniquet

Hemingway’s pen might as well have been a scalpel when he wrote: “Scott, write truly, no matter who it hurts.” This surgical advice cuts deeper than mere stylistic preference—it reveals the circulatory system of powerful writing. The best prose doesn’t just bleed; it controls the hemorrhage with precision.

Consider Sylvia Plath’s The Bell Jar. Before publication, her publisher demanded removal of 70+ references deemed too raw—the literary equivalent of applying pressure to a wound. Yet the novel’s power persists precisely where Plath refused to sterilize her truth: Esther Greenwood’s clinical depression retains its jagged edges even through veiled metaphors. This tension between exposure and restraint defines what I’ve come to call hemostatic writing—the art of stopping just short of exsanguination.

The Symbolic Organ Method

When direct truth-telling risks destroying relationships or traumatizing readers, Hemingway’s contemporaries developed ingenious workarounds. Virginia Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own transforms feminist rage into architectural metaphor. Kafka’s The Metamorphosis packages familial alienation in chitinous insect limbs. These writers understood what emergency physicians know: sometimes you need indirect pressure to stop the bleeding.

Try this diagnostic exercise with your own vulnerable material:

- Identify the wound – What raw experience feels dangerous to expose? (e.g., childhood abuse)

- Find its anatomical counterpart – What object shares its properties? (e.g., a cracked porcelain doll)

- Transplant the nerves – Transfer the emotional weight to the symbol (e.g., describing the doll’s fractures in forensic detail)

Contemporary memoirist Joan Didion mastered this in The Year of Magical Thinking, where her grief materializes not through weeping, but through obsessive recounting of medical procedures. The clinical language becomes her hemostat.

The Ethics of Transfusion

Every truth-teller faces this paradox: absolute honesty can destroy the very relationships that feed your writing. Hemingway’s solution? Write now, publish later. His posthumously published A Moveable Feast settled decades-old scores—safely after the affected parties had died. While few would advocate this extreme, timing matters.

Consider these filters before exposing fresh wounds:

- The Obituary Test: Would this description still feel necessary if the subject died tomorrow?

- The Mirror Rule: Can I look at my reflection while writing this?

- The Legacy Check: Does this serve readers, or just my vindication?

When novelist Ocean Vuong wrote On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous, he fictionalized his abusive father into a character named “Trev.” This nominal transfusion allowed truth to circulate while protecting living connections.

Your Hematology Report

Track your writing’s vital signs with these diagnostic tools:

Clotting Time

How long can you sit with discomfort before retreating into safer prose? Time yourself writing an unvarnished scene vs. one using symbolic displacement.

Platelet Count

Analyze a recent piece: what percentage of painful truths did you dilute with metaphor? Under 30% suggests risk of hemorrhagic shock for readers; over 70% may indicate artistic anemia.

Remember: Hemostatic writing isn’t about diminishing truth—it’s about ensuring the patient (your story) survives to reach the OR (publication). As trauma surgeon-writer Atul Gawande demonstrates in Complications, sometimes the most honest writing wears gloves.

The Eavesdropper’s Manifesto: When Writers Become Professional Spies

Hemingway’s fourth piece of advice cuts against everything we’ve been taught about creativity. While most writing guides urge you to “look inward,” he told Fitzgerald something radical: “You’ve been listening to the answers to your own questions for too long.”

This wasn’t criticism—it was diagnosis. The drying up of a writer, Hemingway suggested, happens when we stop observing the world and become trapped in our own echo chambers.

The Observation Paradox

Creative writing professors love assigning journaling exercises. “Write about your childhood memories!” they say. “Mine your personal trauma!” But Hemingway recognized a dangerous pattern: when writers only listen to themselves, their work becomes insular, repetitive, and—frankly—boring.

Virginia Woolf called these rare moments of heightened awareness “moments of being.” Joan Didion kept notebooks filled with strangers’ mannerisms. David Sedaris still rides the subway specifically to harvest dialogue. The raw material of great writing isn’t in your navel—it’s in the couple arguing over coffee at the next table.

Field Guide for Literary Spies

- The Coffee Shop Recon Mission (Beginner Level)

- Bring a small notebook (phones create barriers)

- Record:

- Physical tics (a man checking his watch 7 times/minute)

- Sentence fragments (“…the divorce papers said…”)

- Environmental details (the way sunlight hits a half-empty ketchup bottle)

- Pro tip: Wear headphones (people speak freely around “disconnected” listeners)

- The Hemingway Iceberg Drill (Advanced)

- When overhearing dialogue, write only the visible 10% (what’s said)

- Then infer the submerged 90% (the fight they’re not mentioning, the job loss implied by their shoes)

- Compare with later observations—this trains subtext creation

- Digital Eavesdropping (21st Century Adaptation)

- Save intriguing text message typos (autocorrect failures reveal subconscious)

- Collect viral Reddit comments with unusual phrasing

- Archive Zoom meeting chatter (note how virtual spaces alter speech patterns)

The Ethics of Literary Surveillance

A writer at the next table scribbles as you argue with your partner. How dare they? But also—how thrilling. There’s an unspoken contract: we’re all potential material. The rules:

- Never record identifiable information (medical details, full names)

- Change at least three key characteristics before using real people

- If someone notices you observing, buy them coffee (the spy’s tax)

Your Eavesdropper’s Toolkit

- A “Wild Dialogue” Bank

Create a digital folder or physical notebook exclusively for stolen phrases:

“The doctor said my cholesterol is… wait, is that guy writing this down?”

—Overheard at Denny’s, 3:17 AM

- The 5-Minute Eavesdrop Sprint

Set a timer during your next:

- Uber ride

- Grocery line wait

- Dog walk

Capture every sensory detail (not just words—the click of a lighter, the crinkle of a pastry bag)

- The Rewilding Exercise

For every hour spent writing, spend 15 minutes:

- Watching construction workers banter

- Eavesdropping on teenagers at the mall

- Studying how baristas handle the morning rush

Hemingway wasn’t just being poetic when he said “That’s where it all comes from. From seeing, from listening.” He was giving tactical instructions. The writer’s real work begins long before the first sentence—it starts when you stop narrating your life and start transcribing the world.

Today’s Spy Assignment: Go to a public space and write down one conversation verbatim. Don’t edit. Don’t judge. Just record. Notice how real speech includes false starts, interruptions, and half-thoughts—everything your “polished” dialogue lacks.

The Alchemy of Pain: Turning Raw Emotion into Literature

Hemingway’s advice to Fitzgerald cuts deeper than craft—it’s a surgical manual for emotional dissection. “Be as faithful in seeing your pain as a scientist would be,” he writes, drawing an unexpected parallel between the laboratory and the writer’s desk. This isn’t about catharsis; it’s about controlled transformation.

The Three-Stage Distillation Process

- Centrifuge Stage (Separation)

Separate facts from feelings. When Karl Ove Knausgård describes his father’s death in My Struggle, he doesn’t just vomit grief onto the page. He isolates physical details—the way light fell on the corpse’s eyelid, the smell of cleaning products—creating emotional distance through microscopic observation. - Filtration Stage (Contextualization)

Run your experience through universal themes. Consider how The Kite Runner transforms personal guilt into an exploration of betrayal across cultures. Your “I hate my father” becomes a scene where a boy watches his friend get assaulted, mirroring the silent complicity we all recognize. - Crystallization Stage (Artistic Form)

Give shape to the shapeless. Joan Didion’s The Year of Magical Thinking takes the amorphous fog of widowhood and crystallizes it into numbered sections—not because grief follows chronology, but because the human mind demands structure to process chaos.

The Uncomfortable Truth About Therapeutic Writing

Studies in expressive writing show a paradox: journals filled with “I feel” statements rarely produce compelling literature. Hemingway instinctively knew what psychology now confirms—raw emotion needs processing to resonate. When you write “My chest aches with loneliness,” you’ve described a symptom. When you show an old man counting sugar packets at a diner (as Raymond Carver did), you’ve created diagnosis through implication.

Try this tonight:

Take any painful memory and:

- Describe it clinically (“The hospital room measured 12×15 feet”)

- Find its mythological parallel (Is this your Persephone moment?)

- Contain it in a formal constraint (Write exactly 300 words, no adjectives)

Hemingway wasn’t advocating emotional detachment—he was teaching us to harness emotion’s voltage without being electrocuted by it. Your pain matters not because it’s yours, but because you’re willing to forge it into something that illuminates ours.

Writing Through the Storm

Fitzgerald’s hands shook as he opened Hemingway’s letter in 1934. His wife Zelda was institutionalized, his latest novel had flopped, and creditors circled like vultures. The golden boy of the Jazz Age now faced a question every struggling writer recognizes: How do you create when your world is crumbling?

Hemingway’s response cut through the despair with characteristic bluntness: “We are only writers and what we are supposed to do is write.” This wasn’t dismissive—it was the distilled wisdom of someone who’d written through war wounds, four marriages, and chronic depression. His prescription contained two radical ideas that still startle modern creators:

The 300-Word Lifeline

Clinical studies now confirm what Hemingway intuited: consistent micro-writing (even 15-30 minutes daily) maintains neural pathways crucial for creativity. During Fitzgerald’s worst years—when he claimed to produce “nothing but garbage”—he actually wrote 300-500 words daily. These fragments became:

- Unpublished short stories later mined for The Last Tycoon

- Journal entries revealing his wife’s illness with startling clarity

- Letters that scholars now consider autobiographical literature

Modern equivalent: Author Emily St. John Mandel wrote sections of Station Eleven on her phone during her child’s chemotherapy sessions.

The 0.05% Rule

Hemingway famously warned Fitzgerald about alcohol’s “slow murder” of creativity. Neuroscience explains why: at 0.05% BAC (about one drink), the prefrontal cortex—responsible for narrative structure and emotional nuance—begins shutting down. Yet many writers (including Hemingway himself) believed liquor “loosened” creativity. The compromise?

- Pre-writing ritual: 30 minutes of manual activity (sharpening pencils, arranging desk) to transition into flow state

- Post-writing reward: The celebrated “writer’s drink” after hitting daily word count

- Damage control: Fitzgerald’s 0.15% BAC days yielded incoherent drafts; his 0.05% days produced salvageable material

Case Studies in Catastrophe Writing

- Stefan Zweig

Wrote The World of Yesterday while fleeing Nazi Europe, moving between hotels with a single suitcase. His method:

- Wrote first drafts on whatever paper was available (menus, train schedules)

- Used historical parallels to process personal trauma (“When I describe Marie Antoinette’s exile, I’m describing my own”)

- Rachel Carson

Completed Silent Spring while undergoing radiation for breast cancer:

- Scheduled writing sessions around nausea cycles

- Framed environmental damage as a metaphor for her body’s betrayal

The Survival Algorithm

For writers in crisis, try this Hemingway-inspired formula:

(Creative Output) = (Minimum Daily Words) × (Cognitive Capacity)

Where:

Minimum Daily Words = 300 (about 1 printed page)

Cognitive Capacity = (Health Baseline) - (Stress Factors)Example: When Fitzgerald was managing Zelda’s medical bills (Stress Factor: 0.7), his workable output was 300 × (1.0 – 0.7) = 90 words. Those 90 words kept his writer identity alive until recovery.

Your Turn: The 7-Day Shipwreck Journal

Hemingway believed writing during disasters creates our most authentic work. Try this:

- Day 1-3: Describe your crisis in raw, unfiltered sentences (“I’m terrified about _“)

- Day 4-5: Re-write one section using metaphorical language (turn layoffs into “factory closures of the soul”)

- Day 6-7: Identify one universal truth in your personal storm

As Hemingway scribbled in a 1935 letter now at the JFK Library: “The best writing comes from men who are being eaten by wolves—but never stop taking notes.”

The Hemingway Challenge: Writing Through the Chaos

That typewritten letter from Key West still smells of saltwater and whiskey if you read it closely enough. Hemingway’s words to Fitzgerald weren’t just advice—they were a lifeline thrown across the chasm of creative despair. Now it’s your turn to grab hold.

The 7-Day Survival Kit for Writers

- Day 1-2: Embrace Your Garbage

- Task: Write 500 words knowing you’ll discard 450

- Hemingway hack: Type with newspaper covering your screen

- Why it works: Removes the temptation to edit prematurely

- Day 3: Character Autopsy

- Take one fictional person you’ve created and answer:

- What would their real mother say about your portrayal?

- What secret would they never tell you?

- Modern example: How Celeste Ng fact-checked immigrant parents in Little Fires Everywhere

- Day 4: Dangerous Truths

- Write one paragraph that would:

- Make your childhood best friend uncomfortable

- Get you disinvited from a family gathering

- Safety valve: Store it in a password-protected file for 30 days before rereading

- Day 5: Eavesdrop Like a Criminal

- Visit a coffee shop or park, capture:

- Three verbatim conversation fragments

- One unexplained physical gesture

- Pro tip: Use voice memo app to capture rhythm

- Day 6: Pain Under Microscope

- Take a recent emotional experience and write it three ways:

- Raw diary entry

- Third-person short story

- Metaphorical description (e.g., “The disappointment was a spoiled peach…”)

- Day 7: Write Through Disaster

- Simulate adverse conditions:

- Write with TV blaring news

- Use terrible pen/old keyboard

- Set impossible deadline (20 minutes for 300 words)

- This is how Margaret Atwood drafted The Handmaid’s Tale during subway commutes

The Unedited Truth About Editing

That manuscript you’re hoarding? The one waiting for “one more polish”? Hemingway would tell you what he told Fitzgerald—send it anyway. The Paris Review archives prove even his cleanest drafts contained spelling errors and continuity flaws. What made them literature wasn’t perfection, but the bloodstains left from wrestling truths onto paper.

Your move:

- Hit reply right now with which challenge day scares you most

- Forward this to one writer friend who’s been “getting ready to write” for too long

- Remember what gets measured gets done—track your daily wordcount in a visible place (fridge door, phone lock screen)

The best writing advice always ends the same way: stop reading about writing, and write. Even if it’s terrible. Especially if it’s terrible. Your masterpiece is buried in the next ninety pages of what you’re currently afraid to put on paper.

“We are all apprentices in a craft where no one ever becomes a master.”

—Ernest Hemingway’s deleted preface to A Moveable Feast