The other day, while waiting for students to arrive, a colleague mentioned how today’s kids don’t recognize Lucille Ball or understand why we loved I Love Lucy so much. That casual remark lingered with me longer than expected. Had I failed my own children by not properly introducing them to these cultural touchstones of my generation? I’d tried a few times, but the humor that once had me in stitches barely registered with them.

This generational disconnect isn’t just about television preferences—it’s about how the things that shaped us inevitably fade into obscurity. We cling to these cultural artifacts not just out of nostalgia, but because their disappearance feels like losing pieces of ourselves. There’s something profoundly unsettling about watching what once felt universal become historical curiosity.

That conversation about Lucille Ball followed me home. It colored how I saw our upcoming spring break trip to Las Vegas—a destination I’ve never particularly enjoyed, but was visiting to see Dead and Company perform at the Sphere. To break up the desert drive, I planned a stop at Calico Ghost Town, a place I hadn’t visited since a family trip fifteen years ago. Back then, my oldest was just a baby, and our family circle included people who are now gone—my father-in-law, my sister-in-law, my husband Kenneth. The thought of returning with my now pre-teen and teenage children carried unexpected weight.

What does it mean to revisit places heavy with memory when so many of the people who made those memories are no longer here? How do we bridge the gap between what we want to pass down and what actually resonates with the next generation? These questions about cultural transmission and the passage of time would shape our entire trip in ways I couldn’t yet anticipate.

As we packed for Vegas, my kids groaned about the ghost town detour. ‘It’ll be boring,’ my twelve-year-old declared. But I remembered how Kenneth had loved Calico as a child, how he’d described the bottle house made of glass and the mining history. Those stories felt important to share, even if I couldn’t tell them with his particular warmth and humor. Maybe especially because I couldn’t.

This tension between holding on and letting go, between honoring the past and living fully in the present, would become the throughline of our journey—just as it’s become the throughline of my life since loss reshaped our family. The ghost town awaiting us seemed an apt metaphor for all these unanswerable questions about what endures and what inevitably fades away.

The Forgotten Classics and Frozen Time

Standing by my classroom door between periods, a colleague’s offhand remark about students not recognizing Lucille Ball lingered in the air like chalk dust. ‘Kids these days don’t know I Love Lucy,’ she sighed, the disappointment in her voice mirroring my own unspoken concerns. I mentally scanned through my children’s media consumption – the YouTube shorts, the TikTok dances – wondering when classic television had become historical artifact rather than shared cultural currency.

This generational cultural gap manifests in subtle but profound ways. Recent Nielsen data shows only 12% of Gen Z can identify Lucille Ball, compared to 89% of Baby Boomers. The black-and-white comedy that shaped American humor now plays to empty virtual living rooms where algorithm-driven content reigns. My own attempts to introduce the series to my kids ended with polite boredom – the physical comedy that once sent my generation into fits of laughter now seemed as distant as vaudeville.

Our insistence that younger generations appreciate these cultural touchstones reveals more about our own psychology than theirs. Clinical psychologist Dr. Linda Olson’s research on nostalgia identifies this as ‘cultural preservation anxiety’ – the unconscious fear that when our references become obsolete, parts of our identity might disappear with them. The shows, music, and artifacts that formed us serve as psychological landmarks; when no one else recognizes them, we experience a peculiar loneliness, as if our personal history is being erased.

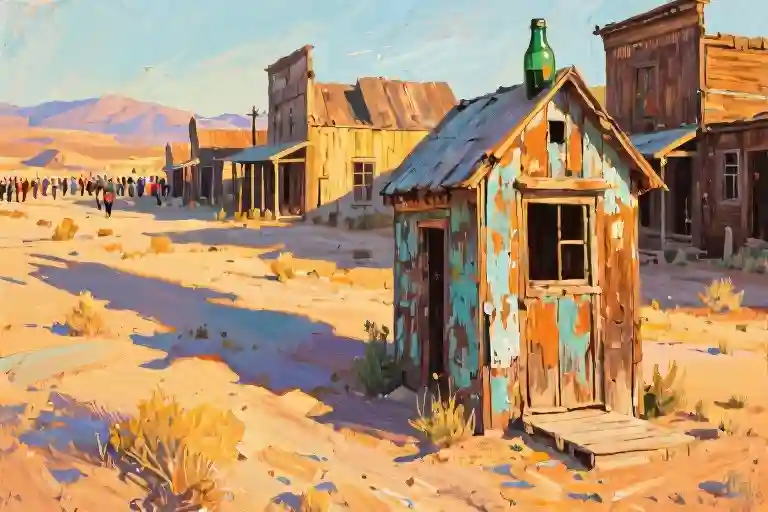

This tension between preservation and progress came into sharp relief during our family’s recent visit to Calico Ghost Town. The crumbling bottle houses and abandoned mines stood as perfect metaphors for how cultural memory decays – once bustling centers of activity now reduced to museum exhibits. Walking those dusty paths, I realized how quickly the vibrant present becomes the curated past. The same forces that turned Calico into a tourist attraction were quietly at work on my own childhood references, preparing them for display in the cultural archives.

Perhaps this explains why we cling so tightly to the media of our youth. In sharing I Love Lucy with disinterested children or dragging reluctant teens through historic sites, we’re not just passing along entertainment – we’re fighting to keep our lived experiences from becoming artifacts behind glass. The irony, of course, is that in doing so, we risk becoming like Lucy Lane, Calico’s last resident – caretakers of memories no one else shares, living among ghosts of what once was.

Yet even as I mourn the shows and songs that shaped me, I recognize this cycle as inevitable. The cultural spring from which we all drink continues to flow, even as its waters take new forms. My children will have their own defining shows and shared references that will one day seem equally alien to their children. The challenge lies not in forcing them to appreciate our classics, but in understanding what creates meaning for them – and perhaps finding the courage to engage with their world as enthusiastically as we want them to engage with ours.

Ghost Town Reflections: When Memories Outnumber the Living

Standing in the dusty main street of Calico Ghost Town, I held up my phone to compare two photos separated by fifteen years. The first showed my husband Kenneth grinning with our oldest child – then a baby – perched on his shoulders, my father-in-law leaning against a wooden post with that quiet smile of his. The second photo captured my three pre-teens squinting in the same sunlight, their postures echoing their father’s and grandfather’s in ways that made my breath catch. Four generations distilled into two frames – except now, 4/5 of the people in that original photo were gone.

The Mojave wind carried whispers of Lucy Lane’s story as we passed her former home. The last resident of Calico had lived here until 1969, tending memories of a vanished community. For thirty years after her husband’s death, she became the keeper of stories in this fossilized mining town. Watching my children poke through the bottle house – the same one Kenneth had described visiting as a boy – I understood Lucy’s peculiar loneliness. There’s a special ache in being the rememberer, the one who bridges what was and what is.

My youngest interrupted my thoughts by tugging my sleeve. ‘Did Daddy really get his pocketknife here?’ he asked. I hesitated. The details had begun to blur – was it Calico or Sequoia? Nine years of grief had taught me how memories behave like desert wildflowers: vivid in season, then retreating until you’re no longer certain of their exact shape. Earlier, I’d confidently told the kids about their father’s childhood visit, but now fragments of other stories surfaced. Had he mentioned running track in high school, or was it cross country? The more I grasped for precision, the more the grains slipped through my fingers.

We paused near the old schoolhouse where Lucy Lane would have studied as a girl. The wooden floors creaked differently now under my children’s sneakers than they had under her leather boots. That’s when the realization struck me – my kids weren’t just inheriting Kenneth’s stories; they were creating their own Calico memories. Their laughter bouncing off the saloon walls, the way my daughter dramatically pretended to faint when I suggested we tour the mine shaft again. These moments would become their nostalgia someday, just as Kenneth’s pocketknife (wherever he got it) had become part of our family mythology.

The desert light shifted, casting long shadows from the Calico Mountains. Somewhere in my phone lived that other photo – Kenneth’s childhood version, his father young and strong beside him. Three generations of men, now reduced to stories and a stubborn pocketknife mystery. Time had done its cruel arithmetic: our original family quintet now represented by four graves and one bewildered widow. Yet here we stood, my new configuration of loved ones, adding fresh layers to this haunted place.

As we boarded the miniature train (after considerable pre-teen protest), Peter’s declaration echoed in my mind: ‘We only live once! I’m going to live big.’ The engine chugged past Lucy Lane’s house, past the bottle house that might or might not have featured in Kenneth’s childhood adventure. The tracks curved around a bend where the modern world disappeared, and for three minutes, we existed outside time – ghosts to someone else’s future memories, living fully in our fragile, fleeting now.

The Concert Epiphany

Standing inside the Sphere in Las Vegas, surrounded by pulsating lights that mirrored the constellations, I felt the opening chords of Eyes of the World vibrate through my chest. The Dead and Company concert wasn’t just a musical event—it became a sanctuary where grief and joy held hands under neon skies.

When Lyrics Become Lifelines

The line “Wake up to find out that you are the eyes of the world” landed differently that night. For years I’d heard this Grateful Dead classic as background music, but now—nine years into navigating loss—the words unfolded like a personal manifesto. The song’s paradoxical imagery (beaches and seasons within a heart) mirrored my own emotional landscape, where sorrow and gratitude had learned to coexist.

Back home, I fell into a rabbit hole of interpretations. Music critics dismissed it as “hippy dippy” nonsense, but Reverend Turner from our Buddhist temple would argue otherwise. At his last dharma talk, he’d explained how songs are like koans—their meaning shifts with the listener’s life experiences. “The same melody that scores someone’s wedding day might accompany another’s deepest mourning,” he’d said. That night in Vegas, Eyes of the World became my anthem for choosing presence amid impermanence.

The Alchemy of Shared Experience

What startled me most was realizing how the Sphere’s collective energy transformed individual listening into communal healing. Thousands of strangers—each carrying unseen burdens—swayed together as the lyrics “we all drink from the same spring” rippled through the arena. A tattooed biker wiped his eyes near me; a college student hugged her friends. In that moment, the song ceased being just Jerry Garcia’s poetry and became a mirror reflecting our shared human condition.

This revelation reshaped how I approach generational gaps too. My kids may never appreciate I Love Lucy or 70s jam bands, but our recent breakthrough came via an unexpected medium—TikTok. Last week, my daughter showed me a viral clip sampling Eyes of the World, sparking a conversation about how music bridges eras. Perhaps cultural transmission isn’t about replicating our nostalgia, but creating spaces where new generations can discover their own connections.

Carrying the Torch Forward

The concert’s afterglow lingers in small but significant ways. I’ve started a family ritual: Sunday mornings now feature “song interpretation breakfasts” where we analyze lyrics from different genres. My son surprised me by comparing Post Malone’s Circles to Buddhist concepts of cyclical suffering—proof that wisdom whispers through unexpected channels.

As Rupi Kaur wrote, “you see beauty because you carry it within.” Those shimmering hours at the Sphere taught me that grief, like music, isn’t meant to be solved—only witnessed, shared, and allowed to evolve. Now when Eyes of the World plays through my headphones during school drop-offs, I smile knowing Kenneth would love that our kids are growing up with eyes—and hearts—wide open.

The Gift of Grief: Holding Both Sorrow and Joy

Standing in line for that silly little train ride at Calico Ghost Town with my protesting pre-teens, I had one of those crystalline moments where time collapses in on itself. Peter’s earnest declaration – “We only live once! I’m going to live big” – hung in the desert air alongside the ghostly whispers of all the families who’d stood in this same spot before us. My husband Kenneth’s childhood photo flashed in my mind, his gap-toothed grin framed by the same bottle house we’d just visited. Nine years gone, yet somehow present in every chug of the miniature locomotive.

This is the paradox grief teaches us to hold: the deepest sorrow and the brightest joy can occupy the same heartspace. Like Rupi Kaur’s exquisite observation about beauty – “it means there is beauty rooted so deep within you you can’t help but see it everywhere” – grief reshapes our vision. The same eyes that trace absent loved ones in old photographs learn to spot their fingerprints in unexpected places: a particular chord progression at a Dead and Company concert, the way desert sunlight catches on broken glass in a ghost town’s bottle house, a child’s spontaneous decision to abandon teenage cynicism for a whimsical train ride.

The Practice of Seeing

After Kenneth’s death, I developed unconscious rituals to sustain this dual vision:

- The Daily Beauty Log – Each evening, I note three specific moments where joy pierced through the grief fog. Yesterday’s entries:

- The way my daughter’s laughter echoed in Calico’s empty schoolhouse

- Discovering Walter Knott’s connection between this ghost town and our local amusement park

- Peter squeezing my hand during Eyes of the World when the lyrics “the heart has its seasons” played

- Memory Mapping – Instead of straining to perfectly preserve every detail about Kenneth (Did he get that pocket knife at Calico or Sequoia?), I trust the important memories will surface when needed. Like how his Disneyland train ride photo resurfaced exactly when I needed to appreciate our own silly Calico railway moment.

- Generational Bridge-Building – Rather than forcing my kids to appreciate I Love Lucy, we create new shared touchstones. That Dead and Company concert may become their version of my Lucy nostalgia – something they’ll someday wistfully try (and fail) to make their own children love.

The Alchemy of Absence

Grief performs strange alchemy. The same loss that hollows you out creates new chambers to hold unexpected treasures. That Vegas trip revealed several:

- Musical Epiphanies: Eyes of the World became my unexpected anthem. Not because of any definitive meaning (even Deadheads debate the lyrics), but because hearing it live while surrounded by my children felt like Kenneth whispering: “Wake up to find out that you are the eyes of the world.”

- Teenage Vulnerability: My older kids’ last-minute decision to join the train ride – their reluctant surrender to childhood’s fleeting magic – became a sacred glimpse behind their adolescent armor.

- Interconnectedness: Learning about Lucy Lane, Calico’s last resident, who spent decades keeping stories alive in a ghost town. Isn’t that what we all do with our dead? Tend the flickering lights of their memory in the quiet museums of our hearts?

Both/And Thinking

Western culture loves binaries: happy/sad, past/present, holding on/letting go. But real healing lives in the contradictions:

- I can miss Kenneth desperately and relish my independent life

- My children may never love I Love Lucy and we’ll create our own classics

- Calico is both a graveyard of dreams and a playground for new memories

That Dead and Company concert held space for all these truths. The “hippy dippy” lyrics some critics mocked became my lifeline – not because they offered easy answers, but because they honored life’s beautiful complexity. Like Reverend Turner said at the Buddhist temple, meaning isn’t fixed in songs (or in grief); it emerges in the listening.

Carrying the Gift Forward

Nine years into widowhood, I’ve learned grief isn’t something you “get over” like a cold. It’s more like learning to play a complex instrument – some days you fumble the chords, other days you channel something transcendent. The music keeps changing, and so do you.

My advice to fellow travelers on this path:

- Let specific places (ghost towns, concert venues) hold multiple timelines simultaneously

- Allow songs/poems to mean different things at different stages of healing

- When nostalgia for lost traditions arises, ask: Am I preserving or imprisoning these memories?

- Practice Kaur’s “beautiful seeing” daily – it rebuilds your capacity for wonder

That Calico train ride now lives in our family lore alongside Kenneth’s Disneyland photo. Two moments separated by decades, united by the same truth: life’s most ordinary magic (silly trains, sticky churro fingers, impromptu concerts) becomes extraordinary when viewed through eyes polished by loss. Grief’s cruelest gift is teaching us to spot these fleeting wonders before they slip into the past.

We board our little trains. The tracks diverge. The scenery blurs. But sometimes – if we’re very lucky – we catch glimpses of other travelers waving from parallel rails, their faces alight with the same hard-won joy.

The Spring We Share

Standing in the desert silence of Calico, watching my children board that absurd little train, I understood something fundamental about grief and growth. The same spring that quenched my husband’s childhood thirst now nourishes our children’s laughter as the locomotive chugs through the ghost town. Different configurations, same essential water.

Nine years of navigating loss has taught me that grief operates in paradoxes. It’s the heaviest weight and the sharpest lens. The cruelest thief and the most generous teacher. When the Dead and Company played Eyes of the World beneath the Sphere’s cosmic light show, the lyrics landed differently than they would have a decade ago:

“Wake now discover that you are the song that the morning brings / But the heart has its seasons, its evenings and songs of its own”

This is the gift of surviving loss – realizing we’re all temporary custodians of memories, traditions, and love. We don’t own them; we simply borrow them to share with the next traveler at the spring. My children may never appreciate I Love Lucy as I do, just as I’ll never fully grasp what brings them joy in their digital worlds. But when Peter declared “I’m going to live big” before that train ride, I recognized the same spirit that made his father grin on Disneyland’s Casey Junior ride.

Rupi Kaur was right about beauty being a reflection of what we carry within. The generational cultural gap isn’t a failure; it’s evidence of life continuing. Those of us standing between fading memories and emerging futures have a sacred responsibility – not to force-feed nostalgia, but to demonstrate how to drink deeply from each moment.

So I’ll leave you with this question: What do your Eyes of the World see today? Is it:

- The way morning light catches dust motes in your childhood home?

- Your teenager’s eye roll that somehow still contains affection?

- A song that means everything and nothing all at once?

Look closely. The spring is right there.