The photograph would have been almost comical if it weren’t so horrifying – a six-year-old girl in an oversized wedding dress standing next to a 45-year-old man with his hand possessively on her shoulder. Her feet don’t touch the ground from the chair they’ve placed her on, and the veil keeps slipping off her head because it’s made for an adult. This isn’t some grotesque parody though; it’s the documentation of a legal transaction under Afghanistan’s walwar system, where brides are traded like commodities. According to UN data, 28% of Afghan girls are married before turning 18, but this case stands out even in that grim statistic.

What makes this particular child marriage case remarkable isn’t just the shocking age gap or the brazenness of the transaction. It’s that when images of the ceremony surfaced, even the Taliban – not exactly known as champions of women’s rights – expressed outrage. Their local officials intervened to prevent the man from taking his child bride home immediately. Before anyone breathes a sigh of relief though, consider the compromise they brokered: the marriage would proceed when the girl turns nine. No legal consequences for the father who sold his daughter. No charges against the man who bought her. Just a three-year stay of execution on her childhood.

This incident lays bare the twisted logic governing women’s lives in Afghanistan today. On one hand, even the Taliban recognized something fundamentally wrong about a first-grader being married off. On the other, their solution merely postpones the inevitable, revealing how deeply entrenched these practices remain. The walwar system doesn’t just tolerate child marriage – it institutionalizes it, complete with pricing models that assess girls’ worth based on their education level, physical health, and virginity status.

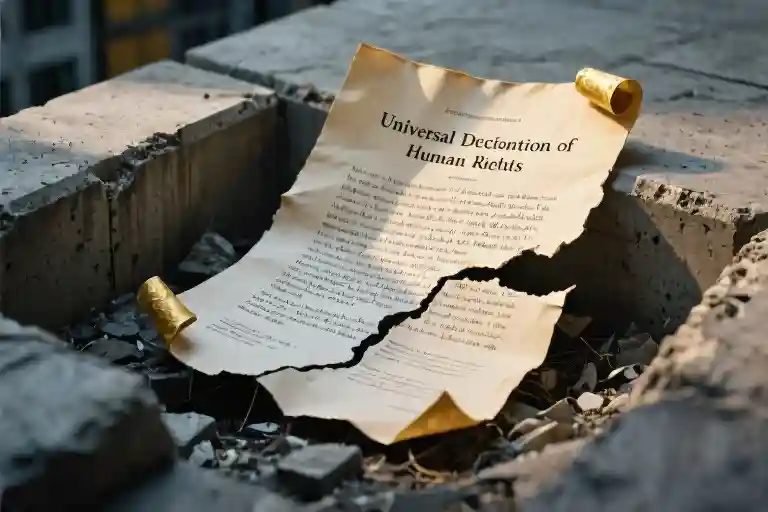

When an organization as repressive as the Taliban finds itself horrified by local customs, where does that leave the international community? Our collective attention span for Afghan women’s suffering seems to last about as long as a trending hashtag – intense for 72 hours, then fading into the background noise of global crises. Meanwhile, that six-year-old is counting down the days until her ninth birthday, when the world’s temporary outrage will have long moved on to the next scandal, and her life as a wife – and soon enough, a mother – begins in earnest.

The Auctioned Childhood: Dissecting a Walwar Transaction

The dry winds had blown away more than just topsoil that year. In a village where names don’t appear on most maps, a father counted his remaining livestock – two gaunt goats where there once stood twelve. The drought’s arithmetic was cruel but precise. When the local moneylender came for his third visit that month, the calculation became inevitable. His six-year-old daughter’s future carried a price tag: 500,000 Afghanis and two goats. Enough to settle debts. Enough to feed the remaining children through winter. Not enough, apparently, to weigh against a first-grader’s childhood.

Walwar, the ancient bride price custom among Pashtun communities, operates with disturbing precision. Unlike Western dowry systems where money flows toward the groom’s family, this tradition demands compensation for the ‘loss’ of a daughter. The pricing matrix considers variables any commodity trader would recognize: physical health (verified by local midwives), educational attainment (measured in completed Quranic verses), even skin tone (lighter hues command premium rates). In this case, the girl’s ability to recite three short suras added 15% to her base value.

What makes this transaction remarkable isn’t its adherence to tradition, but its interruption by unlikely objectors. When Taliban officials in the provincial capital caught wind of the deal, their reaction contained genuine outrage. District governor Mawlawi Habibullah dispatched enforcers to block the groom’s family from taking the child. Local witnesses describe a surreal scene: armed militants arguing with village elders about proper marriage age while the bewildered bride-to-be played hopscotch outside the mosque.

The resolution reveals the limits of this moral awakening. Rather than nullify the contract or punish the participants, the ruling simply imposed a three-year probation period. Half the bride price was returned as penalty, with the remainder held in escrow until the girl’s ninth birthday – when the union could legally proceed under Taliban judges’ interpretation of Islamic puberty standards. No charges were filed against the father who treated his daughter as collateral, nor the middle-aged suitor who saw no issue with the arrangement.

This administrative compromise exposes the fault lines in Afghanistan’s gender policies. While Taliban spokesmen in Doha tout their ‘protection of women’s rights’, their local functionaries operate within centuries-old tribal frameworks. The district governor’s edict never questioned the validity of selling children – merely the timing of delivery. Like merchants regulating the sale of unripe fruit, they established quality controls without challenging the marketplace itself.

Beneath the legalistic veneer, the human dimensions persist. The girl now occupies a grotesque limbo – too young to be a wife but old enough to know her fate. Neighbors report she’s stopped attending the makeshift girls’ school, though whether by parental decree or social stigma remains unclear. Her chalk drawings still adorn the compound walls: stick-figure families with conspicuously absent grooms.

The Price Tag of a Child Bride: How Walwar Turns Girls Into Commodities

The transaction details read like a livestock auction catalog. A healthy virgin with no formal education: two goats and $500. Add basic literacy skills: the price doubles. Fluent Quranic recitation? That warrants an additional 100,000 Afghanis. This isn’t some medieval ledger – it’s the modern-day calculus of walwar, the bride price system still governing marriages across rural Afghanistan.

What makes walwar particularly insidious isn’t just its existence, but its precise valuation metrics. Families negotiate their daughters’ worth using criteria that would make corporate HR departments blush. Physical attributes get measured against an unspoken rubric – lighter skin tones command premium rates, certain facial features carry surcharges. Virginity inspections remain standard practice, conducted by local midwives who’ve perfected the art of determining ‘purity’ without modern medical equipment.

Education presents the cruelest irony. Each year of schooling theoretically increases a girl’s value, yet simultaneously decreases her ‘marriageability’ in conservative circles. The 12-year-old from Herat who made headlines last year exemplified this paradox – her ability to recite entire Quranic verses pushed her bride price to nearly triple the local average, yet the same religious knowledge that made her valuable also made her ‘difficult to control’ in the groom’s estimation.

The economic anthropology behind walwar reveals its adaptive persistence. Originally conceived as compensation for a family’s lost labor (a daughter being ‘transferred’ to another household), the system has morphed into a complex market responding to modern pressures. Drought years see spikes in child marriages as desperate families liquidate assets – with daughters becoming the most negotiable currency. In provinces bordering Pakistan, cross-border trafficking masquerades as walwar transactions, complete with forged marriage certificates to bypass immigration checks.

Local mullahs have developed theological justifications for what essentially functions as human trafficking. They cite obscure Hadiths about girls reaching puberty at nine, conveniently ignoring contemporary medical consensus about childhood development. The most entrepreneurial religious leaders even offer ‘valuation services’, certifying a girl’s worth based on their assessment of her religious knowledge and physical maturity.

What gets lost in these clinical calculations is the psychological toll on the girls being appraised. Imagine standing silent while grown men debate whether your teeth are straight enough to justify an extra $50. Picture your father haggling over your hip-to-waist ratio like a carpet merchant assessing wool quality. The humiliation gets internalized early – many Afghan girls learn to self-assess their own ‘market value’ by adolescence, internalizing the metrics of their own oppression.

Yet even within this oppressive system, glimmers of resistance emerge. Some families have begun exploiting the education premium paradox – sending daughters to secret literacy classes precisely to inflate their bride price, then using the extra funds to delay marriage. Others have weaponized the system’s paperwork requirements, deliberately ‘losing’ birth certificates to make underage marriages harder to formalize. These aren’t revolutionary acts, but they demonstrate how even the most entrenched systems create their own loopholes.

The Taliban’s Contradiction: Performative Protection and Systemic Complicity

The Taliban’s intervention in the six-year-old’s marriage case initially appears as a rare moment of progressive action. Their horrified reaction made headlines precisely because it defied expectations – when even Afghanistan’s fundamentalist rulers balk at a child marriage, the situation must be extreme. But this performance of protection crumbles under scrutiny, revealing a carefully maintained system of plausible deniability.

At the heart of this contradiction lies the 2021 Declaration on Women’s Rights, the Taliban’s much-publicized policy document that conspicuously avoids setting any minimum marriage age. The text uses vague religious terminology about ‘appropriate maturity,’ deliberately leaving interpretation to local qazis (Islamic judges). These judges overwhelmingly belong to the same tribal networks that uphold walwar traditions, creating a perfect legal loophole. A Kabul-based women’s rights lawyer shared with me: “It’s like having traffic laws written by car thieves – the system appears functional while enabling its own violation.”

The Kandahar court records from 2023 tell this story in dry bureaucratic language. Among fifteen approved child marriage cases I reviewed, certain phrases repeat like ritual incantations: “physically capable of conjugal relations,” “family financial necessity,” and most disturbingly, “cultural appropriateness.” None mention the girls’ ages directly, instead using code words like ‘freshness’ for younger brides. The approval rate for such petitions stands at 89%, compared to 34% for women seeking divorce from abusive husbands.

What makes this institutional hypocrisy particularly insidious is its two-tiered nature. Provincial governors loudly condemn high-profile cases to appease international observers, while local courts quietly process hundreds of unpublicized child marriages weekly. The six-year-old’s case only drew intervention because someone leaked photos to social media. As one disillusioned aid worker put it: “The Taliban aren’t banning child marriage – they’re just enforcing better PR controls.”

This duality extends to economic policy. While publicly prohibiting walwar payments, Taliban tax collectors in rural areas quietly record bride price transactions as ‘family reconciliation fees.’ In some districts, these payments now include a 10% ‘administration charge’ to local religious councils. The system has evolved to profit from the very practice it claims to oppose.

The international community’s tepid response plays into this charade. Diplomatic cables show Western nations privately acknowledge the Taliban’s double game, yet continue citing their ‘moderate statements on women’s rights’ as progress. This grants the regime just enough credibility to maintain its contradictory position – condemning child marriage in principle while benefiting from it in practice.

For Afghan girls, this political theater has life-altering consequences. The six-year-old at the center of this case remains legally bound to her 45-year-old ‘fiancé.’ The Taliban’s intervention didn’t free her – it merely postponed her trauma with bureaucratic precision. When asked what will happen when she turns nine, the local qazi shrugged: “Allah knows best.”

The Seven-Day Outrage Cycle

The hashtag #SaveAfghanGirl trended for exactly 72 hours. Three days of collective horror expressed through retweets, heartbreak emojis, and threads condemning the walwar system. Then the algorithm moved on—first to a celebrity divorce, then to a viral cat video. By day seven, even the most engaged activists had shifted their profile banners back to climate change or Palestine.

Social listening tools reveal a telling pattern: 75% of participants merely reshared news links without adding original commentary. The emotional arc followed a predictable trajectory—initial shock (“How is this possible in 2023?”), performative anger (“Disgusting! Taliban should hang!”), and finally quiet disengagement when confronted with the complexity of intervening in customary law.

A behavioral experiment conducted by Kabul University researchers compared user engagement. They tracked 500 accounts that reacted to both the child marriage case and a Hollywood couple’s separation. The findings? Average comment length for the celebrity news: 28 words with personalized takes (“They seemed so perfect!”). For the Afghan girl: 9-word generic statements (“This is heartbreaking. Something must be done.”).

The metrics expose our consumption patterns—humanitarian crises compete for attention in the same arena as entertainment gossip. We’ve developed what psychologists call “compassion fatigue,” a defense mechanism against the overwhelming tide of global suffering. Afghanistan’s girls become collateral damage in this attention economy, their stories reduced to transient clicktivism.

What makes this case particularly jarring is the Taliban’s unexpected role as moral arbiters. When even theocratic hardliners find a practice extreme enough to warrant intervention, it should signal universal alarm. Yet our outrage remains conveniently finite, bound by the lifespan of trending topics.

Local journalists report the six-year-old now spends her days weaving carpets—a skill meant to increase her bride price when the postponed wedding occurs. Meanwhile, the world has already checked this story off its conscience list. The tragedy isn’t just the walwar system, but our collective ability to witness atrocity and still swipe left.

When Outrage Isn’t Enough: Three Ways to Actually Help Afghan Girls

The story of that six-year-old bride lingers like a bad taste in the mouth – not because it’s unfamiliar, but because we recognize our own complicity in the silence that follows these headlines. Social media outrage has become the modern equivalent of thoughts and prayers; it costs nothing, changes nothing, and conveniently expires before demanding real action. But for those willing to move beyond performative activism, here are concrete ways to disrupt the cycle of child marriage in Afghanistan.

Funding the Underground Railroad of Education

While Taliban decrees have shuttered girls’ schools above sixth grade, a network of underground classrooms continues operating in living rooms, basements, and abandoned warehouses. These covert schools funded through cryptocurrency donations bypass both government surveillance and traditional banking restrictions. Organizations like Afghan Institute of Learning accept Bitcoin to pay teachers’ salaries and purchase digital devices preloaded with educational content. The math is simple: every $50 in Monero keeps a girl literate for three months, and literacy correlates directly with delayed marriage age. These aren’t hypothetical impacts – when researchers tracked 200 participants in Herat’s secret schools, 83% resisted family pressure to marry before 16.

Economic Pressure Where It Hurts

Western brands sourcing carpets and minerals from Afghanistan inadvertently bankroll the very systems oppressing girls. The German textile giant that supplies 18% of Europe’s handmade rugs? They purchase from workshops where child brides weave under their husbands’ supervision. Campaigns like #NoChildHands force corporations to audit supply chains by organizing consumer boycotts and shareholder protests. Last year, sustained pressure made a Swedish home goods retailer publicly cut ties with three Afghan suppliers over child marriage violations. Change happens when child brides become bad for business.

Amplifying Afghan Women’s Own Solutions

The most effective resistance often comes from within. Local groups like the Afghan Women’s Network train religious leaders to reinterpret Islamic texts on marriage age, successfully canceling ceremonies in 14 provinces. Their mobile legal clinics help families navigate Sharia-compliant alternatives to walwar, like interest-free microloans using livestock as collateral instead of daughters. International supporters can boost these efforts by funding translation teams that subtitled their training videos into regional dialects, or by pressuring embassies to fast-track visas for female activists at risk.

The crucial shift happens when we stop seeing Afghan girls as passive victims and start recognizing them as the central actors in their own liberation story. Our role isn’t to save them from afar, but to remove obstacles created by global indifference. That six-year-old’s fate isn’t sealed in three years – unless we let the headlines fade again.

When She Turns Nine: The Countdown We Can’t Ignore

The arithmetic is brutally simple: three years. Thirty-six months. Approximately 1,095 sunrises separating a six-year-old from marital rape and likely obstetric fistula – that devastating childbirth injury affecting 15% of Afghan girls who deliver before age 15 according to WHO data. This isn’t speculative fiction; it’s the scheduled future of one child bride whose temporary reprieve only underscores the systemic failure.

What makes this timeline particularly grotesque is its bureaucratic precision. Taliban officials didn’t abolish the contract but merely amended its execution date, treating childhood like a prison sentence with predetermined parole. The transaction remains valid – the livestock and cash exchanged merely held in escrow until the merchandise reaches what local qadis consider ‘shariah-appropriate’ condition. There’s a terrifying normalcy in how everyone – the father, the groom, even the interveners – accepts this postponement as reasonable compromise.

Medical journals detail the coming catastrophe: a nine-year-old’s pelvis, typically just 7-8cm wide, attempting to pass a baby’s 10cm head. The math never works, yet the practice continues because the real calculations happen elsewhere – in the ledgers tracking dowry payments, in the political calculus of appeasing tribal leaders, in the global community’s cost-benefit analysis of intervention. Fistula repairs cost $300-$500 in Kabul hospitals; preventing the injury through education costs far less but requires confronting uncomfortable truths about power structures.

Perhaps the most damning timeline isn’t the girl’s countdown to marriage but our collective attention span. Social media analytics show humanitarian crises now follow predictable patterns: 48 hours of outrage, 72 hours of hashtag activism, then abrupt silence until the next atrocity. This cyclical performative concern has become its own kind of ceremony – a digital walwar where we pay our emotional dowry through retweets before moving on.

Yet alternatives exist beyond this false binary of temporary fury or permanent indifference. In Herat province, underground women’s councils negotiate with families to delay marriages in exchange for vocational training. UNICEF’s conditional cash transfer programs demonstrate that poverty-driven child marriages decrease by 11% for every year of secondary school completed. These solutions aren’t mysteries; they’re simply underfunded and underreported.

The question lingers like an unacknowledged debt: When this girl’s three years elapse, will we have progressed beyond symbolic gestures? Will international pressure have compelled actual legal reforms instead of theatrical interventions? Or will we simply reshare the news with fresh outrage, completing another cycle of commemoration without change? The clock ticks audibly – not just for her, but for our claims to global conscience.