My parents were never married in the Catholic Church. That simple fact carried more weight in mid-century America than most people today could imagine. For our family, it wasn’t just a technicality—it was a border we couldn’t cross, an invisible barrier that shaped our lives in ways I only came to understand much later.

The air in our home always carried a peculiar tension, like the lingering scent of a dead skunk you can’t quite locate. My father, a cradle Catholic, had married my mother in a quiet civil ceremony in Indianapolis. No priest presided over their vows, no stained-glass windows witnessed their promises. Just two people in love, signing papers in some government office.

At the time, they probably thought they were being practical. My mother wasn’t Catholic—she came from Quaker roots—and the Church’s rules about mixed marriages felt like unnecessary complications. What they didn’t realize was how that single decision would ripple through our lives, coloring everything from Sunday Mass to family gatherings to how neighbors looked at us.

The Catholic Church of the 1950s recognized civil marriages, but with a crucial caveat: they considered them valid in the eyes of God while refusing to acknowledge civil divorces. This theological paradox meant that once married—whether by judge or priest—you were bound until death. My parents’ courthouse wedding created a peculiar limbo: technically married by state standards, yet living in sin according to the parish down the street.

I remember the way my mother would tense slightly when filling out forms that asked for religion. The hesitation before checking ‘Catholic’ even though she attended Mass more faithfully than half the congregation. The careful way she’d avoid taking Communion, standing aside while the rest of us filed forward. These were the unspoken rules we all learned, the dance steps to a song nobody wanted to hear but everyone kept playing.

Years later, I’d piece together why our family carried this particular cross. It wasn’t just about my parents’ mixed marriage—it traced back to my mother’s first husband, a man named Marshall who disappeared from her life before I was born. That brief, disastrous marriage in her youth became the chain the Church wouldn’t break, the obstacle no amount of Sunday attendance could overcome.

What fascinates me now isn’t just the rules themselves, but how they bent the shape of ordinary lives. How doctrine could make a woman who prayed every morning feel unworthy by supper time. How a institution built on forgiveness could be so relentless in its accounting. And how love—real, messy, stubborn love—found ways to grow even in the shadow of disapproval.

That’s the story I want to tell: not about theology, but about people. Not about what was forbidden, but about what endured.

The Marriage That Didn’t Count

Growing up Catholic in 1950s America meant living within invisible fences. Cross one, and you’d find yourself in unfamiliar territory – not just socially, but spiritually. My parents’ marriage existed in that strange borderland, recognized by the state of Indiana but not by the Catholic Church. That distinction shaped our family’s life in ways I didn’t understand until much later.

The Church had clear rules about marriage back then. A civil ceremony like my parents’ small Indianapolis courthouse wedding? Valid in the eyes of the law, but meaningless in the eyes of God. Canon law required Catholics to marry before a priest, unless they’d obtained something called a “dispensation” – special permission granted in advance. My father, raised Catholic, didn’t have one. My mother, not Catholic at all, didn’t know such a thing existed.

They tried to do things properly. I learned this in bits and pieces over years – how they’d approached their parish priest, filled out paperwork, sat through uncomfortable conversations. The process felt designed to discourage. Endless forms, cold bureaucratic language, requirements that shifted like sand. What should have been a joyful step became a maze of canonical hurdles.

The annulment process for my mother’s previous marriage presented another impossible barrier. In the 1950s, declaring a marriage null required navigating a Byzantine system:

- Filing a formal petition through a willing priest

- Providing detailed testimony and witness statements

- Waiting through a tribunal investigation

- Enduring a second review for confirmation

- Finally receiving a decision – often years later

No part of this system considered the human cost. My mother’s first marriage had lasted barely four months – a rushed union with a man nearly twice her age that collapsed during her pregnancy. Yet proving this invalid required money, connections, and stamina she didn’t possess. Without an annulment, the Church saw her as permanently married to that first husband, making any subsequent union – including hers with my father – adulterous by definition.

What struck me later wasn’t just the rules themselves, but their arbitrary cruelty. Had my mother never married her first husband, had I been born out of wedlock, the Church would have considered her free to marry my father properly. The greater sin, it seemed, wasn’t bearing a child outside marriage, but attempting to legitimize that relationship without Church approval.

My parents eventually stopped trying to navigate this impossible system. They built their life together outside it – a life the Church refused to recognize, but which contained more genuine love and commitment than many “valid” marriages I witnessed. Still, that exclusion left marks. My father, a practicing Catholic, likely faced questions at confession. My mother, though she attended Mass with us, couldn’t receive Communion. The message was clear: our family existed at the edges of God’s grace.

Looking back, I see how these rules served institutional power more than spiritual truth. The Church could have offered mercy – could have seen my mother not as a problem to be solved, but as a faithful woman doing her best. Instead, it chose rigidity, enforcing boundaries that turned faith from a comfort into a weapon. The real miracle isn’t that my parents’ marriage survived those pressures, but that their love for each other – and for us – remained so completely ordinary in its extraordinary strength.

The Theological No-Man’s Land: My Mother’s Marriage Shackles

Marshall Walters was 36 years old when he began pursuing my mother – a 20-year-old Quaker girl who knew as much about sex as she did about nuclear physics. Their courtship lasted barely a month, one of those whirlwind postwar romances where young women traded caution for the promise of stability. I arrived exactly nine months after their hastily arranged wedding night, a living calendar marking the duration of their disastrous union.

By the time my mother’s pregnancy entered its fourth month, the marriage had unraveled with startling speed. Twice Marshall drove her back to her mother’s house in Indianapolis. The second time, he delivered his parting shot to my grandmother: “You better not let her come back.” And just like that, my biological father exited stage left, leaving behind a confused young wife and an unborn child.

This abbreviated marriage would haunt my mother for decades, not because she mourned its loss, but because the Catholic Church refused to acknowledge its end. In those pre-Vatican II days, the annulment process resembled less a spiritual journey than an ecclesiastical obstacle course designed to weed out all but the most persistent (or wealthy) petitioners.

The Annulment Gauntlet of the 1950s:

- The Paper Chase: Initiating the process required navigating a maze of canonical forms, often without clear guidance from overworked parish priests. My mother, barely literate in Catholic bureaucracy, stood little chance.

- The Witness Problem: Required testimony from “knowledgeable parties” about the failed marriage’s defects. But who could testify? The husband who abandoned her? The small-town Indiana neighbors who whispered about “that divorced Quaker girl”?

- The Money Pit: Filing fees, notary costs, and “tribunal expenses” stacked up quickly – a significant burden for a single mother working menial jobs in the 1950s Midwest.

- The Waiting Game: Even successful petitions could take years, during which the applicant remained in canonical limbo – technically still married, forbidden from entering any new sacramental union.

What fascinates me now is the cruel irony buried in these rules. Had my mother never married Marshall at all – had I been born out of wedlock from a brief affair – the Church would have considered her free to marry my father without complication. The greater sin, it seemed, wasn’t illegitimate children but legitimate marriages conducted beyond Rome’s purview.

My mother never spoke openly about these matters. I pieced together her story through half-overheard conversations, documents left carelessly on tables, and the careful silences that descended when certain topics arose. The shame clung to her like static electricity – invisible but ever-present, sparking when least expected.

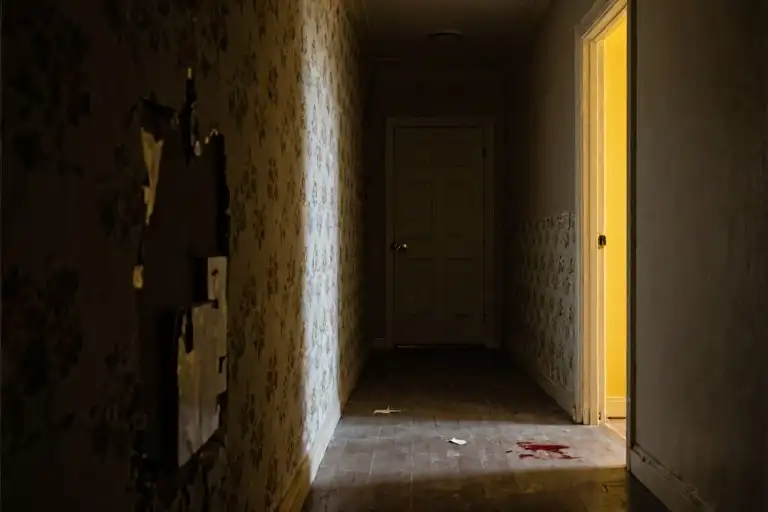

Twice I caught her crying over paperwork at the kitchen table, hastily wiping her eyes when she noticed me. Once, I found a yellowed wedding photograph torn neatly in half, with Marshall’s portion missing entirely. These fragments suggested more than any direct confession could have – the weight of that failed marriage, the bureaucratic purgatory it created, and the unspoken knowledge that in the eyes of the institution that shaped our family’s life, she would always be someone else’s wife.

The Church’s Absurd Compromise: When Married Couples Were Told to Live as Siblings

There’s a particular kind of absurdity that arises when rigid institutions collide with human realities. The Catholic Church’s proposed ‘solution’ for couples like my parents – married civilly but not in the Church – ranks high on that list. They called it ‘living as brother and sister,’ a phrase that still makes me shake my head decades later.

Imagine being told that the man you’ve built a life with, shared a bed with, raised children with – that this person must now be considered your sibling in the eyes of God. The theological gymnastics required to maintain this fiction would challenge even the most devout. Yet this was the actual pastoral advice given to countless couples in mid-century America when they found themselves outside the Church’s narrow definitions of valid marriage.

My parents never told me if a priest actually suggested this arrangement to them. Knowing their personalities, I suspect they would have burst out laughing at the sheer impracticality of it. My mother, practical to her core, would have pointed out the obvious: ‘And what exactly do we tell the children? That Daddy is suddenly my brother?’ The mental image of my straight-laced father trying to explain this theological loophole to neighborhood busybodies still brings a smile to my face.

This bizarre recommendation reveals much about the Church’s priorities at the time. The appearance of propriety mattered more than actual human relationships. Physical separation wasn’t required – you could continue sharing a home, raising children together, presenting yourselves as a married couple to the world. The only thing that needed to change was what happened behind closed doors. As if God (and the parish gossips) were keeping some celestial spreadsheet tracking marital intimacy.

The irony cuts deeper when you consider the alternative scenario. Had my mother never married my biological father at all – had I been born out of wedlock from a brief affair – the Church would have considered her ‘free to marry’ my father without any annulment process. A child born outside marriage carried less spiritual baggage than a marriage performed without Church approval. The math of sin, it seems, followed its own peculiar logic.

This double standard exposes the uncomfortable truth that Church rules often had less to do with spiritual purity than with maintaining control. A wedding certificate from a courthouse represented defiance of Church authority in a way that premarital sex did not. The former challenged institutional power; the latter could be framed as human weakness deserving of mercy (provided, of course, one felt sufficient remorse).

What gets lost in these theological contortions are the actual people caught in the middle. My mother, who wanted nothing more than to join her husband’s faith fully. My father, torn between the Church he loved and the woman he’d chosen. The children (myself included) who grew up sensing but not understanding why our family didn’t quite fit the mold.

The ‘brother and sister’ suggestion wasn’t just impractical – it was dehumanizing. It reduced a decades-long marriage, with all its complexity and commitment, to a single physical act. It asked people to deny the reality of their deepest relationships to satisfy an institution’s paperwork requirements. Most tragically, it kept sincere believers like my mother on the outside looking in, not because they rejected faith, but because faith’s gatekeepers couldn’t accommodate life’s messy realities.

Looking back, I sometimes wonder how many priests actually believed this was a workable solution versus how many were simply boxed in by canon law they had no power to change. The Church of the 1950s operated like a vast, inflexible bureaucracy where rules took precedence over people. Compassionate clergy found themselves forced to offer absurd compromises because the system allowed for no other options.

My parents ultimately chose reality over pretense. They remained married in every sense that mattered – sharing a home, a bed, and a life – even if the Church refused to recognize it. Their marriage lasted until death did part them, proving more enduring than many ‘valid’ unions blessed by the Church. In the end, perhaps that’s the most powerful rebuttal to all the theological hair-splitting – a love that persisted despite every obstacle the institution could throw its way.

The Faith That Lived Outside the Rules

She knelt by the bed every night, hands folded against the quilt patterned with fading roses. The same quilt that covered me when I had childhood fevers, the one she’d smooth while murmuring prayers to a God whose official representatives had spent years telling her she didn’t belong. My mother—the woman the Church refused to recognize as properly married—was the most devout person in our house.

This irony wasn’t lost on me, even as a child. While my Catholic father often slept through Sunday mass, it was my ‘living in sin’ mother who got us dressed, who wiped our faces with damp washcloths, who shepherded us into the pew with whispered reminders to stop fidgeting. She couldn’t take Communion, but she knew all the responses by heart. The parish priests who eyed her with polite suspicion had no idea she’d memorized the Act of Contrition long before they’d finished seminary.

There’s a particular cruelty to being told you’re unworthy of something you already possess. My mother didn’t need the Church’s permission to have faith—she carried it with her like the worn rosary beads in her coat pocket. What she lacked was the official stamp, the bureaucratic approval that would let her participate fully in the rituals that clearly meant so much to her. I used to watch her during the Eucharistic prayer, how her lips would move slightly when the rest of the congregation said ‘Lord, I am not worthy that you should enter under my roof…’ The words came easily to her, even as the actual sacrament remained forever out of reach.

The Church had its reasons, of course. Canon law isn’t written in pencil. But as I grew older, I began to notice something unsettling about their ironclad rules—how they seemed to value paperwork over people, how a missing signature mattered more than decades of fidelity. My parents stayed married for forty-two years. Not ‘as brother and sister,’ but as husband and wife in every sense that actually impacts human lives—through mortgage payments and cancer scares and raising children who never once doubted their commitment. Meanwhile, Marshall Walters (that phantom first husband who haunted our family’s spiritual life) had vanished before my first birthday, leaving behind nothing but a name on documents that somehow held more weight than real, lived devotion.

What does it mean to be ‘married in the eyes of God’? If we’re to believe the catechism, God sees hearts rather than legal filings. Yet the Church’s labyrinthine annulment process suggested otherwise—as if divine grace could only flow through properly notarized channels. The more I learned about canon law, the more it resembled tax code rather than spiritual guidance. Three witnesses forms signed in triplicate, tribunal fees that might as well have been notary publics, appeals processes that dragged on longer than some marriages. All this to determine whether a long-dead union between two barely-adults had been ‘valid’ in the first place.

My mother never spoke bitterly about it. That wasn’t her way. But sometimes, when we’d drive past the cathedral where my friends’ parents had been married, she’d sigh in a particular tone I couldn’t quite decipher—not quite envy, not quite resentment, but something quieter. The sigh of someone standing outside a party they weren’t invited to, even though they’d brought the best dish.

Here’s what the rulebooks didn’t account for: faith isn’t something you can excommunicate someone from. It grows in the cracks between doctrines, flourishes without permission. My mother’s religion lived in the way she turned her face upward during the Gloria, in the care she took ironing our Sunday clothes, in the dollar bills she pressed into our palms for the collection basket even when money was tight. No tribunal could annul that.

Years later, when the Church began softening its stance on annulments under Pope Francis, I thought of all the women like my mother—women who’d loved faithfully but lacked the right paperwork, who’d been told their devotion didn’t count unless stamped and approved. I wondered how many had slipped away, not from lack of belief, but from exhaustion at trying to prove they deserved it. The rules may change, but the hurt remains in the families that absorbed it like old bruises.

Perhaps this is the real test of any faith: not how well it guards its borders, but how widely it draws its circle. My mother’s religion didn’t need official recognition to be real. It was there in the bedtime prayers she taught us, in the way she’d cross herself when an ambulance passed, in the quiet determination with which she loved—not until death, but well beyond it.

The Weight of Unseen Rules

The pews were polished to a high gloss every Saturday afternoon in preparation for Sunday Mass. My mother’s hands would glide across the wood with a lemon-scented cloth, though her name would never appear on the parish volunteer roster. She was the one who starched our Sunday shirts, who packed the missals in my father’s leather case, who reminded us to genuflect before entering the row. But in the eyes of the Catholic Church, she remained an outsider—a woman perpetually standing in the narthex, never quite crossing the threshold.

Her exclusion wasn’t due to lack of devotion. The obstacle was far more bureaucratic: a marriage license filed in an Indiana courthouse decades earlier, to a man who’d discarded her before I took my first breath. That civil ceremony—lasting shorter than some baseball games—became the theological barbed wire that kept her from full communion with the Church her husband loved and her children were raised in.

What fascinates me now isn’t the technicalities of canon law, but the human cost of its inflexibility. My mother’s story reveals how religious institutions often conflate control with righteousness. The same Church that preached forgiveness couldn’t overlook a failed marriage from the Truman administration. The institution that celebrated Mary’s compassion showed little to a pregnant twenty-year-old abandoned in 1949.

There’s a particular cruelty in how these rules targeted women. My father, the Catholic, faced restrictions—denial of sacraments, whispered judgments—but my mother bore the heavier burden. She carried the label of ‘occasion of sin’ simply for building a life with the man who raised another’s child as his own. The theological term was ‘scandal,’ but the lived reality was shame without cause, penance without transgression.

Yet here’s what the parish ledger never recorded: her quiet faithfulness. The rosary beads worn smooth in her pocket. The meatless Fridays observed decades after Vatican II loosened the rules. The way she’d hum ‘Panis Angelicus’ while rolling communion-wafer-thin pie crusts. If grace exists in daily living rather than canonical approvals, then sainthood might look like a Quaker woman waking early to iron surplices for Catholic altar boys who weren’t her biological sons.

This isn’t a story of renounced faith. I still light candles in the same cathedral where my parents’ marriage went unrecognized. But I’ve come to see religious institutions as human constructs—flawed, evolving, and occasionally blind to their own contradictions. The same Church that venerates a未婚 mother in Bethlehem made life needlessly hard for one in Indianapolis.

Perhaps that’s the lingering question: not whether my parents’ marriage was valid in God’s eyes, but why the institution claiming to represent Him spent so much energy policing love that endured, while showing such little interest in the love that failed. The answer, I suspect, has less to do with theology than with power—the desire to mark boundaries, enforce compliance, and maintain a system where forgiveness always comes with paperwork.

My mother died without the annulment she never sought in later years. By then, the Church had streamlined the process, reduced the fees, even acknowledged that young women in the 1950s might have entered bad marriages under pressure. But time doesn’t heal all wounds; it just teaches us which scars to stop pressing.

These days, when I pass that Indianapolis courthouse where my parents married, I think about all the invisible lines we draw between sacred and profane, valid and invalid, worthy and unworthy. The building itself makes no such distinctions—its steps are worn smooth by all who enter, regardless of their theological standing. There’s a lesson in that worn limestone: real life happens in the space between the rules, and love often grows best where institutions bother least.