The summer I turned twelve, I found myself hunched in the corner of our Calcutta balcony with a dog-eared copy of The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo, its Swedish brutality seeping into my subtropical afternoon. This wasn’t the typical preteen reading material in our Bengali household, where Rabindranath Tagore’s poetry collections stood neatly arranged on the teakwood bookshelf, their gold-embossed Bengali spines untouched by my hands.

My father could have stopped me—had he been home. Fluent in English from his Oxford days, he possessed that particular postcolonial ease with Western literature. But his consulting job kept him perpetually airborne between Delhi and Dubai, leaving my mother, who read exclusively in Bengali, unaware of the paperback revolution happening in my bedroom. This accidental autonomy became my literary passport, stamped first with Enid Blyton’s wholesome mysteries before venturing into darker territories.

Our apartment compound buzzed with gossip about children’s exam scores and cricket tournaments, never about which ten-year-old had finished The Lost Symbol before geometry class. The unspoken rule in our community dictated that English books belonged either in the classroom or the prayer room—as vocabulary builders or moral guides. Nobody warned my parents about the unsupervised section in the British Council library where I’d eventually discover Stieg Larsson’s damaged heroine between the crisp pages of a brand-new hardcover.

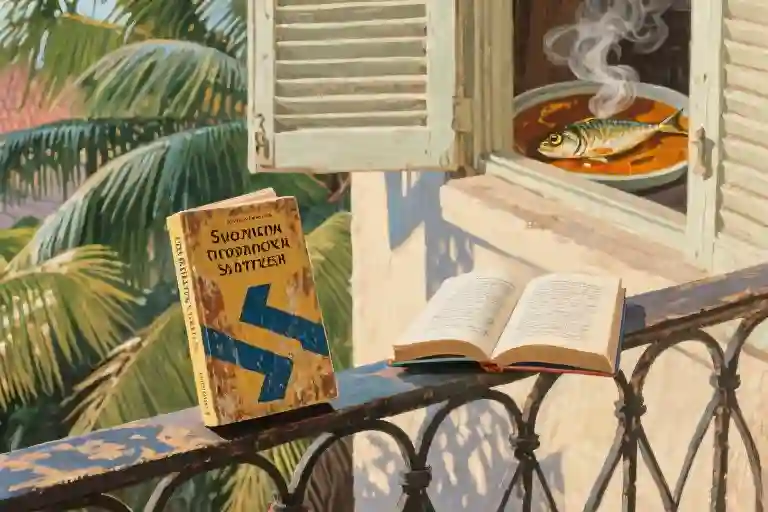

That balcony became my literary no-man’s-land, where Nordic crime fiction collided with the scent of my mother’s fish curry wafting through the jalousie windows. I developed a system: library books concealed beneath math textbooks, reading lights clicked off precisely at parental footsteps, dog-earing pages instead of using incriminating bookmarks. The thrill came not from the adult content itself (though I’ll admit to rereading certain paragraphs in The Da Vinci Code with forensic attention), but from curating my own education beyond the colonial canon of our English-medium school.

Looking back, I recognize the quiet rebellion in those afternoons—not against my culture, but against its accidental limitations. While my cousins memorized Shakespearean sonnets for exams, I was constructing a parallel literary identity through paperbacks that smelled of foreign libraries, their pages subtly warped by humid Indian monsoons. The parental oversight that might have seemed neglectful became an unexpected gift: permission to develop my own literary taste, one controversial bestseller at a time.

The Secret Bookshelf: Enid Blyton’s Reign

Before I discovered the dark alleys of Scandinavian crime fiction, my literary universe orbited around Enid Blyton’s sunlit worlds. Three series dominated my childhood – the Famous Five, Secret Seven, and various mystery collections – each offering a new landscape to colonize with my imagination. These weren’t just books; they were passports to a parallel England of ginger beer and midnight adventures, utterly alien yet completely irresistible to a Bengali girl in Kolkata.

My consumption method bordered on obsessive. Library visits followed a precise ritual: calculate the maximum books allowed (usually seven), finish four by dinner, return tomorrow for more. The characters became more real than my classmates – George’s fierce independence, Julian’s irritating competence, even Timmy the dog’s unwavering loyalty. I could recite entire dialogues weeks after returning the books, much to the annoyance of friends who hadn’t read them.

This wasn’t normal childhood reading. While other ten-year-olds in my neighborhood still struggled through illustrated abridged classics, I’d already plowed through Blyton’s entire catalog twice over. The local librarian started keeping new arrivals behind the counter for me, her eyebrows climbing higher with each increasingly advanced series I devoured. What began as wholesome entertainment became something closer to possession – the kind where you forget to eat until someone physically pulls the book from your hands.

Looking back, I recognize the signs of a mind starved for narratives that matched my reading hunger rather than my age bracket. Blyton provided safety rails – all those picnics and solved mysteries – while quietly preparing me to jump tracks. Her repetitive structures (another island! another secret passage!) built the stamina I’d later need for denser adult fiction. And though I didn’t know it then, those British children’s adventures were my first lesson in cultural code-switching, teaching me to navigate foreign contexts long before I understood what that meant.

The true magic lay in how these stories transformed reading from a solitary act into a secret superpower. While adults fretted over my math scores, nobody noticed I’d developed an uncanny ability to predict plot twists or absorb 300 pages in a single afternoon. These skills, honed on Blyton’s deceptively simple prose, would become the foundation for everything that came after – including that fateful encounter with a certain Swedish thriller at age twelve.

The Forbidden Leap at Ten

By the time I turned ten, Enid Blyton’s universe of ginger beer and midnight feasts began to feel strangely small. The Secret Seven’s adventures suddenly lacked the complexity I craved – not that I could articulate this shift then. It wasn’t rebellion so much as evolution, like outgrowing a favorite sweater that now constricted my movements.

The school library’s children’s section became territory I’d conquered, its pastel-colored spines familiar as old friends. What drew me instead were the thicker volumes on higher shelves, their titles embossed in gold, promising worlds beyond boarding schools and treasure maps. Dan Brown’s The Lost Symbol became my gateway, chosen not for its literary merit (though twelve-year-old me would have fiercely debated this) but because its cover looked important and no one stopped me from taking it.

Reading it felt like being let into a secret club. The sentences were longer, the chapters didn’t always wrap up neatly, and there were concepts I only half-understood – which made the experience thrilling rather than frustrating. I’d pause at passages about noetic science or Masonic rituals, running my fingers under the words as if touch could decode their mysteries. The book smelled different too, that musky paper scent more pronounced than in my well-thumbed Blytons.

There was an unspoken rule among my classmates that certain books belonged to certain ages, like graded readers. Choosing The Lost Symbol broke that rule in ways that felt deliciously transgressive, though the content itself was hardly scandalous. My internal monologue kept up a running commentary: Should I be reading this? Is this what ‘adult fiction’ means? That scene in the library basement felt very… grown-up. The self-consciousness amused me even then – here I was, worrying about fictional characters’ morality while happily bypassing age recommendations.

What no one told me is that reading adult fiction as a child isn’t about understanding everything perfectly. It’s about learning to tolerate ambiguity, to sit with incomplete comprehension. The gaps in my knowledge became spaces for imagination to fill – I constructed my own versions of Washington’s architecture, of Robert Langdon’s academic life, of concepts like ‘philosophy’ and ‘ancient secrets.’ Those misinterpretations were often more valuable than accurate knowledge would have been.

The transition wasn’t smooth or intentional. There were stumbles – books abandoned after fifty pages when the prose proved too dense, moments of embarrassment when adults asked what I was reading. But each attempt stretched my comprehension slightly further, like muscles adapting to new exercises. By the time I encountered The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo two years later, the shock value had less to do with content and more with realizing how far my literary borders had expanded without anyone noticing.

Looking back, that ten-year-old reaching for The Lost Symbol wasn’t being precocious so much as practical. The books available to me didn’t match the questions forming in my mind, so I went searching beyond the designated shelves. What began as logistical problem-solving became a lifelong approach to reading: follow curiosity first, let the labels sort themselves out later.

The Freedom Found Between Shelves

My mother’s bookshelf held leather-bound volumes of Bengali poetry, their gilt-edged pages smelling of pressed flowers and monsoon humidity. On the opposite wall stood my own haphazard collection – Enid Blyton paperbacks with creased spines, library discards bearing unfamiliar surnames in the checkout slips, and later, those thick adult novels with covers too mature for my schoolbag. This physical divide mirrored our linguistic worlds: her Rabindranath Tagore in flowing Bangla script, my dog-eared English paperbacks with their crisp BBC accent dialogues.

Father’s absence created an unexpected literary liberty. Though fluent in English literature himself, his frequent business trips meant no one monitored my reading choices. There were no raised eyebrows when I brought home Dan Brown instead of Dickens, no questions about why a ten-year-old needed novels with ‘adult’ stamped on their library barcodes. This unsupervised exploration became my secret education – one that school syllabi and cultural expectations couldn’t dictate.

The community library became my third space, neither fully Indian nor Western in its offerings. Its rotating collection of donated paperbacks introduced me to global narratives that our Bengali neighborhood bookshops never stocked. I learned to navigate the Dewey Decimal System like a compass, using it to chart courses beyond my cultural coordinates. Those shelves held no judgment about what a brown girl should or shouldn’t read, only possibilities waiting to be borrowed.

Looking back, this unsupervised reading fostered a peculiar duality. At home, I recited Tagore’s poems during cultural festivals; in library corners, I underlined Swedish street names in Larsson’s crime novels. The books became bridges and escape routes simultaneously – connecting me to worlds beyond my immigrant community while providing shelter from its occasional constraints. My reading life flourished precisely in that gap between parental expectations and personal curiosity, in that fertile borderland where cultural preservation and individual exploration coexisted.

Perhaps this is why The Lost Symbol resonated so deeply – not because it was great literature, but because its themes of hidden knowledge and personal discovery mirrored my own journey. Like Robert Langdon deciphering symbols, I was decoding my place between cultures, one unsupervised library visit at a time.

Looking Back at My Reading Journey

Now when I think about those years of voracious reading, I see both gains and losses that came with my precocious literary adventures. The books I consumed shaped me in ways I couldn’t have anticipated at twelve, sitting cross-legged with Stieg Larsson’s thriller in my hands. There was something exhilarating about reading beyond my age, like sneaking into an R-rated movie – the thrill came partly from the content itself, but mostly from the act of crossing invisible boundaries.

My early exposure to adult themes through literature gave me a vocabulary for complexities that my peers were still sheltered from. I could discuss moral ambiguity, political corruption, and human psychology with surprising nuance for my age. But this came at the cost of childhood innocence – I sometimes wish I’d spent more time in Enid Blyton’s wholesome world of picnics and secret clubs before diving into darker narratives.

The cultural displacement I felt was both mitigated and exacerbated by my reading choices. English literature became my secret homeland, a place where I belonged more completely than in my Bengali community or the international school I attended. Yet this very comfort created distance – the more I inhabited fictional worlds, the harder it became to fully engage with my immediate reality.

Now, as I consider what books might fill my future children’s shelves, I’m torn between two impulses. Part of me wants to carefully curate their literary diet, protecting them from material they’re not ready to process. Another part remembers the electric joy of discovering books my parents didn’t know I was reading, and wants to grant them that same autonomy.

Perhaps the answer lies in balance – maintaining open conversations about reading while respecting their right to private literary exploration. After all, those unsupervised reading sessions taught me more than just plot twists and vocabulary. They taught me how to think independently, how to sit with discomfort, and yes – to bring it full circle – they did teach me a few Swedish phrases from Lisbeth Salander, though certainly not enough to hold a conversation.