They say the second year is harder than the first. I didn’t want to hear that last year. I couldn’t imagine worse.

If you are back there in the shock and trauma of those horrific first few months, don’t look up. Don’t worry about the future. Just focus on today, this hour, this minute. That is all you can do. Be very kind to yourself.

In any case, it’s not true. It’s not harder. Nothing is harder than what you are going through right now.

Unfortunately, it’s not necessarily easier either; just different.

The first year, I was a shattered vase, held together by a hundred caring hands of friends, family, and strangers. Disassociated by the trauma of the months leading to Mike’s death, and then that terrible week, I was there, but not there. I don’t remember much, which is a blessing. When I try and think back, it’s a blur. I re-read my Widow blogs to remind me. Sometimes I capture a fragment; the storms, the police station, telling the children, but I can’t hold it. It slips away, trauma to heal another day.

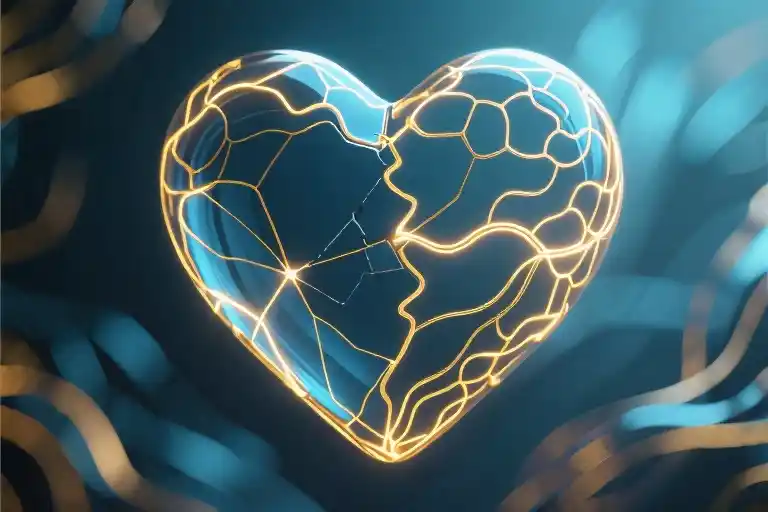

The shock wears off. This is what makes the second year “harder”. The cushioning is gone; reality sets in. Life moves on. For the rest of the world at least. The hundred hands slowly let go, revealing not a kintsugi vase, there are no cracks filled with gold here, but rather a whole new me, unrecognisable from before. Shaken. Fierce. Raw.

I am no longer the most broken of them all. Others now need the hands more than I do. My hands have become one of the hundred, hesitatingly, supporting others. I ache for mothers single-parenting young children under the staggering weight of grief, or for parents frantically trying to keep afloat adult children drowning in mental health battles. Those in that 24/7 horror zone, sleepless, knowing their loved ones are RNotOK but not knowing how or where to get help for someone disintegrating before their eyes.

I couldn’t hold Mike afloat, so I have moved into Sadmin, the seeming never-ending post death administration. I thought I had made progress but, as the fog lifts, I realise that all I had done in that first year was make a list of everything that needed to be done. It is a very good list. On a spreadsheet. With links. I just hadn’t done a single thing on it. So now I am twelve months late starting, the wolves circling, as I only just begin to work through the neverending tasks. It’s hard. It’s stressful. It’s lonely. The “my husband died by suicide, please help me” sympathy has worn off. I am supposed to be able to manage things now. Every ticked box, every finished task, is not about progress. It is the closing up of our life together, the life that vanished in an instant.

One of the many hands that held me together belongs to Emeric. A masseuse and healer extraordinaire, he conjures up menageries to guide me on my journey. If I don’t question and just follow, it works.

He sees this second year as a dingo walking across the desert. There is no other way to reach my destination than to trudge through the barren, scorched earth, scavenging moments of joy along the way. There isn’t a signpost showing where to go or how long the journey will take. But it will be okay, dingos are designed for endurance. They conserve energy, slink low, put one paw in front of the other, until slowly, imperceptibly, the landscape starts to change. The parched sand will give way to gentle slopes of vegetation.

And the dingo wasn’t alone. Emeric could see a fox with him. As he described the fox, I felt an incredible heat in my chest.

“A fire fox” said Emeric. “If it was just the dingo, I would be worried for you. But the fox is wily, creative, energetic. He will help you through.”

In the days that followed, I kept seeing a red, fluffy tail and a cheeky fox face. Except something wasn’t quite right.

“Are you sure it is a fox?” I asked Emeric. “Could it be a Red Panda?”

“A fire fox is a nickname for a Red Panda, yes. “

I send Emeric the book we curated of Mike’s poems — The Red Panda Poetry Book and told him about his spirit animal, the soft toy that he carried with him those last six months that now sits on my desk, watching over me every day.

We All Need A Red Panda To Protect Us

The panda tail didn’t stay bouncing ahead of me for long. In the first year, Mike was everywhere. If I sat quietly, I could call him to me. I could feel his breath in my hair at yoga.

Now, like the hundred hands, I feel him letting us go. Maybe he thinks we are ok now, or at least there is nothing more he can do. Or maybe he needs to go to wherever he is going next. Whatever the reason, I can no longer conjure him at will.

So here I am, alone, making choices.

I am constantly surprised by how active grief forces you to be.

I choose to be kind.

I choose to be grateful.

I choose to take the action I need from my toolkit when life feels overwhelming. I get out of bed, I take a walk, phone a friend, see Emeric.

Some days it is easier than others.

The desert is vast. The dingo keeps moving, and so must I.

They say the second year is harder than the first. I didn’t want to hear that last year. I couldn’t imagine worse.

If you’re back there in the shock and trauma of those horrific first few months, don’t look up. Don’t worry about the future. Just focus on today, this hour, this minute. That’s all you can do. Be very kind to yourself.

In any case, it’s not true. It’s not harder. Nothing is harder than what you’re going through right now.

Unfortunately, it’s not necessarily easier either; just different.

From Shattered to Awake

The first year, I was a shattered vase, held together by a hundred caring hands of friends, family, and strangers. Disassociated by the trauma of the months leading to Mike’s death, and then that terrible week, I was there, but not there. I don’t remember much, which is a blessing. When I try to think back, it’s a blur. I re-read my Widow blogs to remind me. Sometimes I capture a fragment; the storms, the police station, telling the children, but I can’t hold it. It slips away, trauma to heal another day.

The shock wears off. This is what makes the second year feel “harder” to some. The cushioning is gone; reality sets in. Life moves on. For the rest of the world at least. The hundred hands slowly let go, revealing not a kintsugi vase—there are no cracks filled with gold here—but rather a whole new me, unrecognizable from before. Shaken. Fierce. Raw.

That initial period of grief feels like living underwater. Sounds are muffled, movements are slow, and everything appears distorted through the lens of shock. People bring food, send cards, check in daily. You’re surrounded by love but can’t quite feel it through the numbness. The paperwork gets extensions, people make allowances, the world gives you space to simply breathe.

Then gradually, without anyone announcing it, the water recedes. You find yourself standing on dry land, expected to function normally. The memories that were mercifully blurred begin to sharpen at the edges. You notice the empty side of the bed not just in the morning but throughout the day. The silence in the house becomes a presence rather than an absence.

This awakening isn’t dramatic. It happens in small moments: when you automatically set two coffee mugs out instead of one, when you hear a song they loved in the grocery store, when you have to check “widow” on a form. These moments accumulate until you realize the protective fog has lifted entirely.

What remains isn’t the person you were before the loss. That person is gone, along with the life you built together. What emerges is someone fundamentally changed—someone who has stared into the abyss and continues to stand despite the vertigo. The recovery process isn’t about returning to normal but about discovering what normal means now.

You learn to carry the weight differently. The grief that initially crushed you becomes something you integrate into your daily existence. It doesn’t disappear; it becomes part of your architecture, shaping how you move through the world. You develop a new kind of strength, one born not from overcoming pain but from learning to coexist with it.

The second year brings a peculiar clarity. You see relationships more clearly—who stayed, who faded away, who surprised you with their steadfastness. You understand the difference between sympathy and true empathy. Most importantly, you begin to understand yourself in ways that were impossible before the loss.

This transformation isn’t linear. Some days the grief feels fresh again, as if no time has passed. Other days, you notice the sun feels warm on your skin, and you realize you’ve experienced a moment of genuine peace without guilt. These small victories accumulate, building a foundation for whatever comes next.

The new self that emerges isn’t better or worse than the old one—just different. More fragile in some ways, more resilient in others. More aware of life’s fragility but also more appreciative of its beauty. The journey through grief changes your relationship with everything: time, love, loss, and ultimately, yourself.

From Being Held to Holding Others

There comes a point when you realize you’re no longer the most broken person in the room. The realization doesn’t arrive with fanfare or some dramatic moment of clarity. It simply settles in your consciousness one ordinary morning when you’re making coffee, or perhaps when you’re listening to a friend describe their own fresh loss. The hundred hands that held you together begin to loosen their grip not because they care less, but because other emergencies have emerged in other lives.

I noticed the shift gradually. Where once I was the recipient of casseroles, concerned texts, and offers to watch the children, I now found myself asking about others’ struggles. My hands, once limp with grief, began to reach out hesitantly to support others walking this same terrible path. There’s a strange comfort in becoming one of the hundred hands, though the movement still feels unfamiliar, like wearing someone else’s shoes that haven’t yet molded to your shape.

The hierarchy of suffering is a fiction we tell ourselves to make sense of the senseless, but in the quiet spaces between conversations, I find myself aching most for two groups: mothers suddenly single-parenting young children under the staggering weight of fresh grief, and parents frantically trying to keep adult children afloat as they drown in mental health battles. These are the people living in that 24/7 horror zone, sleepless and terrified, watching someone they love disintegrate before their eyes while feeling utterly powerless to stop it.

This recognition brings its own particular sting. I couldn’t hold Mike afloat during his darkest moments, despite trying with every fiber of my being. That particular failure lives in my bones, a permanent resident in my body’s memory. So I’ve done what many of us do when faced with what we cannot fix—I’ve moved into what we’ve come to call Sadmin, the seemingly endless administrative tasks that follow death.

There’s a cruel irony in paperwork. It demands precision and attention at precisely the moment when your brain feels like it’s been replaced with cotton wool. I thought I had made progress in that first year, but as the fog of shock lifts, I’m realizing that all I really accomplished was creating an exhaustive list of everything that needed to be done. It’s a very good list, organized on a spreadsheet with color-coding and hyperlinks to relevant websites. I just hadn’t actually done any of the tasks.

Now I’m twelve months behind where I should be, with deadlines circling like wolves. Each form filled out, each account closed, each bureaucratic hurdle cleared doesn’t feel like progress. It feels like the systematic closing up of a life we built together, the careful dismantling of what vanished in an instant. The sympathy that once accompanied my “my husband died by suicide, please help me” explanations has largely worn off. The world expects functionality now, even when functionality still feels like a foreign language I haven’t quite mastered.

Yet in this space between being supported and supporting others, I’m discovering something unexpected: the act of reaching out to help someone else often helps me too. It’s not about comparing pain or creating some grief Olympics. It’s about recognizing that while our stories differ, the landscape of loss shares certain familiar landmarks. We can point them out to each other, sometimes even helping one another avoid the steepest drops.

The transition isn’t clean or linear. Some days I still need to be held more than I can hold others. Some days the weight of someone else’s pain feels like too much to carry alongside my own. But increasingly, there are moments when offering comfort brings a strange kind of comfort to me as well—a reminder that even in my brokenness, I still have something to give.

This role reversal isn’t about being “healed” or “over it.” It’s about understanding that grief isn’t a linear journey with a clear finish line. It’s more like a series of rooms we move through, sometimes doubling back, sometimes discovering new chambers we didn’t know existed. In some rooms we need to be held. In others, we find we have strength to hold. And sometimes, if we’re lucky, we find ourselves doing both at once.

The Unending Administrative Burden

That first year, I created the most beautiful spreadsheet. Color-coded tabs, hyperlinks to relevant websites, detailed notes on who to contact and what documents were needed. I felt a strange sense of accomplishment looking at that digital masterpiece, this organized compilation of everything that needed handling after Mike’s death. The spreadsheet became my security blanket, my tangible proof that I was “dealing with things” when in reality, I had accomplished exactly nothing.

There’s a particular cruelty to what widows call “Sadmin” – the endless administrative tasks that follow a death. Each item on that list represents another thread connecting you to the life you built together, and each completed task means cutting one of those threads. I moved through those early months in a fog, believing I was making progress because I had created this comprehensive roadmap. The truth was, I had simply mapped out the minefield I would eventually have to cross.

Now, twelve months later, the fog has lifted enough for me to realize my spreadsheet was a beautifully decorated avoidance mechanism. The reality hits with brutal force: I’m not just starting these tasks – I’m starting them a year late. Mortgage companies don’t care about grief timelines. Insurance providers have strict deadlines. The legal system operates on its own schedule, completely indifferent to the fact that my world ended and I needed time to learn how to breathe again.

The sympathy that initially greets “my husband died by suicide, please help me” has a expiration date. By the second year, you’re expected to have your paperwork in order. The patient understanding in people’s voices when you explain your situation has been replaced with impatience and bureaucratic efficiency. “Yes, I understand it’s difficult, but we do need these documents by the end of the month” becomes a familiar refrain, each word another small weight added to the already crushing load.

Every phone call requires rehearsing the story again. “Hello, I’m calling because my husband passed away last year, and I need to…” Each repetition feels like picking at a scab that never quite heals. The person on the other end doesn’t need the details, but the words stick in my throat anyway. Sometimes they offer condolences; sometimes there’s just an awkward silence before they continue with their scripted questions.

There are moments when the sheer volume of it all overwhelms me. Changing names on accounts, closing credit cards, dealing with tax implications, sorting through possessions – each task feels monumental. Some days I manage one small thing from the list. Some days I open the spreadsheet, stare at it for twenty minutes, and close it again without accomplishing anything. The guilt follows both choices: guilt for not doing more, guilt for doing anything at all because each completed task feels like erasing another piece of our life together.

What makes this burden particularly isolating is how invisible it is to others. Friends see you functioning, managing daily life, and assume you’re “through the worst of it.” They don’t see the hours spent on hold with various agencies, the paperwork spread across the kitchen table, the frustration of being passed from department to department. They don’t understand that each checked box on that spreadsheet represents another door closing on the life you planned together.

The financial aspects carry their own special weight. There’s the practical worry about making ends meet, but there’s also the emotional weight of putting price tags on memories. Deciding what to do with his car, his tools, his clothes – these aren’t just practical decisions. They’re emotional negotiations with yourself about what you can bear to keep and what you need to let go.

In the first year, the shock protected me from fully engaging with these tasks. Now, with that cushion gone, each administrative chore lands with direct impact. There’s no buffer between me and the reality that I’m closing up our life together, piece by piece, form by form, phone call by phone call. The spreadsheet that once felt like an accomplishment now feels like a countdown to the final severing of ties.

Yet there’s a strange empowerment that comes with gradually working through the list. Each completed task, however painful, represents a choice to keep moving forward. The administration becomes a tangible way to measure survival, even on days when emotional progress feels impossible. The paperwork doesn’t care about bad days – it needs to be handled regardless, and sometimes that external pressure forces movement when internal motivation fails.

This administrative journey has become my unexpected companion in grief. It’s tedious, painful, and often frustrating, but it’s also concrete evidence that I’m still here, still putting one foot in front of the other, even when every fiber of my being wants to stay in bed. The spreadsheet that began as avoidance has become a map of resilience, each completed task a small victory in the ongoing battle to rebuild a life from the ashes of what was lost.

The Dingo and the Fire Fox

One of the many hands that held me together belongs to Emeric, a masseuse and healer who works in metaphors and menageries. When I arrive at his studio, frazzled by the endless Sadmin and the hollow spaces where Mike used to be, Emeric doesn’t ask how I am. He already knows. Instead, he closes his eyes, places his hands on my back, and begins to describe the animals that appear—spirit guides for this leg of the journey.

He sees the second year as a dingo walking across the desert. There are no shortcuts, no oases in immediate view. The terrain is barren, scorched by a sun that shows no mercy. The dingo doesn’t rush; it knows better. It moves with a slow, deliberate persistence, head low, paws leaving faint prints in the sand. There is no signpost, no map, no certainty of when the desert will end. But the dingo is built for this—for endurance, for survival, for putting one paw in front of the other even when the destination is invisible.

And then Emeric pauses. His hands still. “But the dingo isn’t alone,” he says. “There’s a fox with him.”

As he describes the fox, I feel a sudden, incredible heat bloom in my chest—a quick, fierce warmth that spreads through my ribs. “A fire fox,” Emeric says. “If it were just the dingo, I would worry for you. The desert is long, and loneliness is heavy. But the fox—the fox is clever. Playful. Full of energy and ideas. It will help you through.”

In the days that follow, I can’t shake the image. I see flashes of red fur, a bushy tail, a sly and curious face peeking through the scrub. But something feels off. The creature in my mind isn’t quite a fox. It’s smaller, softer, with rounder ears and a gentler gaze.

I go back to Emeric. “Are you sure it’s a fox?” I ask. “Could it be… something else?”

He smiles. “A fire fox is another name for a red panda, yes.”

And just like that, the world tilts. Mike’s spirit animal was a red panda. For the last six months of his life, he carried a small red panda soft toy with him everywhere—to appointments, to cafes, to the park. It sat on his desk while he wrote. Now it sits on mine, watching me with black glass eyes as I try to untangle the paperwork he left behind.

I send Emeric a copy of The Red Panda Poetry Book, a collection of Mike’s poems we curated after his death. In the introduction, I wrote about how the red panda became his talisman—a creature small and often overlooked, but fierce in its quiet way. Mike loved that they were solitary but not lonely, resilient in their obscurity.

Emeric’s metaphor suddenly deepens, layers folding into layers. The dingo is what I am—steady, stubborn, trudging through the barrenness of grief. But the red panda is what I carry—Mike’s creativity, his humor, his love of words and whimsy. It is the part of him that stays with me, not as a ghost, but as a spark. A fire fox.

Grief is like that. It surprises you with symbols, with connections that feel too precise to be accidental. The healing process is not linear, not a straight path out of the desert. It’s a slow unfolding, a series of small recognitions. You learn to accept the companions that appear—even if they come in unexpected forms.

Some people find comfort in scripture or therapy or long walks. I find it in the silent language of animals that aren’t really there, in metaphors that hold more truth than facts. The dingo doesn’t ask why the desert is vast. It doesn’t hope for a quicker route. It simply moves, trusting that eventually, the sand will give way to grass, the dust to dew.

And beside it, the red panda darts and plays, a flash of crimson in the endless beige—a reminder that even here, especially here, there is room for lightness. For memory. For love that doesn’t die, but transforms.

I don’t know how long this journey will take. But I know I’m not walking it alone.

The Active Path Through Grief

Grief demands motion. This realization still catches me off guard—the way loss, which feels so fundamentally about absence, actually requires a constant series of deliberate actions. In the beginning, I believed sorrow was a state to be endured, a heavy blanket one simply wore until time lightened its weight. But the second year teaches you otherwise. It reveals that grief is not passive; it’s a landscape you must traverse, step by conscious step.

Every morning presents a choice. The bed feels safer, the world beyond the covers too sharp with reminders. But staying there solves nothing, only deepens the ache. So I choose to rise. It sounds small, insignificant in the grand narrative of healing, but it’s the first and most crucial decision of the day. This is what they don’t tell you about the second year: the shock has faded, and with it, the excuse to remain paralyzed. You are left with the raw, unmediated reality of moving forward alone.

I choose kindness—toward myself, above all. The voice of self-criticism is always nearby, questioning every decision, every moment of fatigue, every tear that still comes unexpectedly. I’ve learned to answer it with gentleness. There’s no correct way to navigate this terrain, no timeline to follow. Some days, kindness means accomplishing nothing at all, allowing the sadness its space without judgment. Other days, it means pushing through the administrative tasks that once defined our life together, now reduced to checkboxes on a spreadsheet.

Gratitude, too, has become a conscious practice. Not the glittering, performative kind, but a quiet acknowledgment of small mercies. The sun through the window. A message from a friend who remembers. The weight of the red panda on my desk, a tangible connection to Mike. These moments don’t erase the pain, but they punctuate it, like oases in the desert Emeric described. They remind me that joy and sorrow can coexist, that one doesn’t cancel out the other.

My toolkit is simple, assembled through trial and error. When the walls feel too close, I walk. No destination, no pace to keep—just motion. The rhythm of steps seems to loosen the knots in my chest, the fresh air a temporary cleanse. Some days, the walks are silent, filled with memories. Other times, I call a friend. Not to rehash the pain, but to reconnect with the world outside my grief, to remember I’m still part of a larger tapestry.

Emeric remains a anchor. Sessions with him aren’t escapes from reality, but ways to reinterpret it. Through his guidance, the dingo’s journey across barren land feels less like a punishment and more like a pilgrimage. It’s not about reaching a destination quickly; it’s about endurance, about trusting that the landscape will eventually change. The fire fox—the red panda—darts ahead sometimes, a flash of red in the monotony, a reminder that creativity and energy still exist within me, even on the hardest days.

There are days when the tools feel useless, when the weight is too familiar and the path too long. On those days, I’ve learned to lower the bar. Getting out of bed might be the only victory. Acknowledging that is itself a form of progress. The expectation of constant healing is a trap; grief doesn’t follow a straight line. It spirals, circles back, surprises you with its resilience.

What I’m truly learning, in this second year, is agency. The freedom to choose how I respond to the pain. The power to decide, each day, what survival looks like. It might be tackling one item from the endless Sadmin list, not as an act of closure, but as an act of defiance against the chaos. It might be writing a few lines, or sitting with Mike’s poems, allowing the words to bridge the distance between past and present.

The desert is vast, yes. But the dingo knows how to survive there—how to find sustenance in scarcity, how to keep moving when the horizon seems unchanging. And I am learning, too. Not to outrun the grief, but to carry it with me, to let it shape without defining. Step by step, choice by choice, the path reveals itself. Not as a route out of sorrow, but as a way through it.

The Unending Desert and the Path Forward

The desert stretches out in all directions, an expanse of scorched earth under an unforgiving sky. There are no signposts here, no markers to measure progress. Just the endless horizon and the knowledge that the only way out is through. The dingo moves with a steady, relentless pace—not hurried, not frantic, but persistent. One paw in front of the other, conserving energy, trusting that the landscape will eventually change.

I am that dingo now. Not by choice, but by necessity. Grief does not ask permission; it simply is. And in its wake, it leaves a terrain that must be crossed, no matter how barren or vast. There is no shortcut, no rescue party coming. There is only the trudge forward, the slow accumulation of days, each one a step away from what was and toward what will be.

In the beginning, I kept looking for Mike everywhere. In the quiet moments of early morning, in the familiar corners of our home, in the breath of wind during yoga practice. For a while, he felt close enough to touch. But now, like the hundred hands that once held me, I feel him letting go. It is not abandonment; it is release. Perhaps he knows there is nothing more he can do, or perhaps he trusts that I can now walk alone. Whatever the reason, the palpable sense of his presence has faded. I can no longer summon him at will.

And so, here I am. Alone with my choices.

It is a strange thing, this active burden of grief. We often think of sorrow as passive—a weight that presses down, a shadow that follows. But the truth is, grief demands action. It forces you to decide, again and again, whether to rise or remain fallen. Whether to engage with the world or retreat from it. Whether to tend to the practicalities of life—the Sadmin, the paperwork, the closing of accounts—or let them languish.

I choose to rise. Not every day, and not always gracefully. But I choose it nonetheless.

I choose kindness, especially toward myself. There is no room for self-recrimination here, in this desert. The sun is harsh enough without adding my own criticism.

I choose gratitude, even when it feels like there is little to be grateful for. The warmth of a friend’s voice on the phone, the sight of the red panda sitting on my desk, the simple fact of breath in my lungs—these are small things, but they are things.

I choose action. When the weight feels overwhelming, I reach into my toolkit: I get out of bed. I take a walk. I call someone. I see Emeric. These are not grand gestures, but they are movements forward. And in grief, forward is the only direction that matters.

Some days, the choices come easily. Other days, they feel like miracles. But they are choices all the same.

The red panda is still here. Not always vividly—sometimes just a flicker of red tail in the corner of my mind, a reminder that creativity and energy persist even in the bleakest moments. Mike’s spirit animal, his companion in those final months, now keeps watch over me. It is a thin thread connecting past and present, a symbol of protection and playfulness in a landscape that often feels devoid of both.

Emeric was right: the dingo was not alone. The fox—the fire fox, the red panda—is here too. Cunning, resilient, full of life. It darts ahead sometimes, showing me glimpses of possibility, then circles back as if to say, “I’m still with you.”

This is the paradox of the second year: the loneliness is deeper, but so is the capacity to endure it. The support may have faded, but in its place is a fiercer, more raw version of myself—one that knows how to keep moving even when every step feels like a victory.

There are no conclusions here, no neat endings. Grief is not a problem to be solved but a landscape to be traversed. The desert does not care about my sorrow; it simply exists. And I must exist within it, one day at a time, one choice at a time.

The dingo walks on. The red Panda follows. And I walk with them.