Remember being sick as a child? The fever would break, the cough would subside, and within days you’d be back outside—scraped knees and muddy hands, racing bicycles down the street without a second thought about your recent illness. That remarkable resilience seemed to vanish somewhere between childhood and growing older.

Now consider an elderly person recovering from illness. That same bed rest that once felt comforting becomes something entirely different—a trap that slowly steals strength, balance, and independence. What children bounce back from in days can take weeks or months for older adults, and sometimes they never fully recover.

This phenomenon has a name: deconditioning syndrome. It’s what happens when the body and mind deteriorate through prolonged inactivity, whether from hospital stays, extended bed rest, or simply becoming too sedentary. While we often think of rest as healing, for older adults it can initiate a downward spiral that’s difficult to reverse.

The contrast between childhood recovery and elderly decline reveals something crucial about how we approach healing at different stages of life. Where children naturally resist stillness, older adults often embrace it—not realizing they’re participating in their own decline. This syndrome doesn’t just affect physical capabilities; it diminishes cognitive function, continence, and ultimately, the ability to perform basic daily activities that define independence.

What begins as cautious recovery can end as permanent disability. The bed that offers comfort becomes the place where muscles forget how to work, where balance deteriorates, and where confidence slowly drains away. It’s a quiet crisis happening in hospitals and care homes everywhere, often unnoticed until it’s too late to reverse completely.

Understanding deconditioning is the first step toward preventing it. Recognizing that excessive rest can be as harmful as insufficient rest changes how we approach recovery at any age, but particularly in later life when the margin for error grows narrower with each passing year.

The Hidden Crisis in Bed Rest

We’ve all been told that rest is the best medicine. When you’re unwell, the natural response is to retreat to bed, to conserve energy, to wait it out. This approach works well enough when you’re young—a few days under the covers and you’re back to climbing trees and chasing friends. But as we age, this same prescription can become poison.

Deconditioning syndrome represents one of the most overlooked and dangerous health threats facing older adults. It’s not merely “feeling weak” after illness—it’s a systematic physiological and cognitive decline that occurs during periods of inactivity. The body, when deprived of regular movement and stimulation, begins to dismantle what it no longer perceives as necessary. Muscle fibers atrophy, cardiovascular efficiency drops, neural connections weaken. What makes this process particularly insidious is how quickly it progresses and how profoundly it impacts overall health.

Consider the numbers: for those over eighty, just ten days of bed rest can age muscles by a full decade. The Acute Frailty Network’s research reveals that even twenty-four hours of卧床休息 can reduce muscle power by two to five percent and decrease circulatory volume by up to twenty-five percent. These aren’t abstract statistics—they represent real losses in strength, mobility, and independence. Within the first week of inactivity, lung function begins to decline, skin integrity becomes compromised, and the body’s entire functional capacity diminishes.

The mechanics of this decline follow a predictable yet devastating pattern. Reduced movement leads to muscle weakness, which creates balance problems, which increases fall risk. Each fall further erodes confidence, leading to more sedentary behavior, creating a downward spiral that becomes increasingly difficult to reverse. This isn’t just about physical capability—it’s about dignity, choice, and the ability to maintain one’s identity in the face of health challenges.

What makes deconditioning syndrome particularly challenging to address is its invisibility in early stages. Unlike a fever or visible injury, the initial signs of deconditioning—slight weakness, minor balance issues, increased fatigue—often get dismissed as “normal” aging or expected consequences of illness. By the time the effects become unmistakable, significant rehabilitation may already be required.

The syndrome doesn’t discriminate between hospital settings and home environments. Whether recovering from surgery in a medical facility or convalescing from illness at home, the risks remain equally present. This universality makes understanding deconditioning syndrome essential not just for healthcare professionals but for anyone who might face extended recovery periods or care for aging loved ones.

Recognizing these early warning signs becomes crucial for prevention. The shortness of breath after minor exertion, the faster heartbeat than normal, the discomfort with previously manageable activities—these aren’t just inconveniences but red flags signaling the beginning of functional decline. Addressing them promptly can mean the difference between full recovery and permanent disability.

Understanding deconditioning syndrome requires shifting our perspective on what constitutes “proper” recovery. Sometimes, the most healing action isn’t rest but movement. Not reckless exertion, certainly, but deliberate, appropriate activity that signals to the body that its capabilities remain needed and valued. This paradigm shift—from passive recovery to active rehabilitation—forms the foundation for preventing and reversing this silent health crisis.

The Domino Effect of Deconditioning: From Muscle Loss to Loss of Dignity

When an older adult spends just twenty-four hours in bed, something quietly alarming begins to happen. Muscle power drops by two to five percent. The body’s circulatory volume—the amount of blood moving through your system—can shrink by up to a quarter. These aren’t abstract numbers; they are the first, silent dominoes to fall, setting off a chain reaction that can fundamentally alter a person’s life.

The first seven days of bed rest accelerate this decline dramatically. Muscle weakness becomes more pronounced, the circulatory system continues to contract, and lung function begins to wane. The body, designed for movement, starts to shut down systems it no longer perceives as necessary. This physiological unraveling manifests in a series of tangible, often devastating, symptoms.

Weakness and a profound tiredness become a constant state. This isn’t the pleasant fatigue after a day spent gardening; it’s a deep-seated lethargy that makes the idea of getting up feel impossible. This weakness directly impacts balance. The simple act of standing becomes a precarious event, a wobbling negotiation with gravity. And where there is poor balance, the risk of falls skyrockets. A fall isn’t just a broken bone; for an older person, it can be a catastrophic event that leads to a further loss of independence, a hospital readmission, or a deep fear that prevents them from ever trying to move freely again.

Other symptoms follow closely. Minor exertion, like walking a few steps to the bathroom, triggers shortness of breath and a heart that races uncomfortably fast. Activities that were once routine now bring pain or discomfort. Overall strength and endurance evaporate. The idea of any form of exercise, even the most gentle, feels utterly foreign and far too difficult.

But the impact of deconditioning syndrome extends far beyond the chartable metrics of muscle mass and blood volume. The physical decline attacks a person’s very sense of self. Skin integrity becomes compromised under constant pressure, leading to painful sores that are difficult to heal. Yet, perhaps the most profound losses are the intangible ones: dignity, confidence, independence, and choice.

Imagine needing help for the most private of bodily functions. Imagine being unable to decide for yourself what to wear each day or when to get out of bed. The slow, steady erosion of autonomy is a heavy weight. The person in the bed begins to see themselves not as they once were—a capable, independent individual—but as a patient, a burden, a body that is failing. This psychological toll can be more debilitating than the physical weakness. The desire to simply stay put, to avoid the struggle and the potential for failure, becomes overwhelming. The safe, confined space of the bed becomes both a prison and a refuge, enabling a cycle of further decline. It’s a complex process where the physical and the psychological are inextricably linked, each fueling the other’s descent.

The Prehabilitation Revolution

There’s a profound shift happening in how we approach medical interventions, particularly for older adults facing surgery or significant treatments. It’s called prehabilitation, and it might just be the most important medical concept you’ve never heard of. Dr. Julie Silver from Harvard Medical School beautifully frames it as “some sort of umbrella, offered to patients before they go into the storm.”

This isn’t about intense training or pushing physical limits. Prehabilitation represents a fundamental rethinking of preparation—building resilience before the body faces the trauma of surgery or aggressive treatments. For older adults, this approach can mean the difference between bouncing back and never fully recovering.

The evidence supporting prehabilitation continues to grow. Patients who engage in tailored exercise regimens before surgery experience remarkable benefits: shorter intensive care stays, reduced hospital time, and significantly lower risks of heart and lung complications. But beyond these clinical outcomes, something equally important happens—they maintain greater independence, experience less anxiety, and dramatically increase their chances of returning to pre-treatment activity levels.

Now, I can already hear the objections. What about patients awaiting joint replacements who can barely move due to arthritic pain? Or those with multiple conditions that seem to make exercise impossible? This is where the art of prehabilitation shines. Regimens aren’t one-size-fits-all; they’re carefully adjusted for individual capabilities and limitations. The goal isn’t athletic performance—it’s about preserving what function exists and building whatever additional resilience possible before the storm hits.

The prehabilitation approach extends beyond physical exercise. Comprehensive programs incorporate smoke cessation support for smokers, dietary and weight management guidance, and blood sugar control for diabetics. Each element contributes to creating the most resilient version of the patient possible before treatment begins.

What makes prehabilitation so revolutionary isn’t just the physical benefits—it’s the psychological transformation. Patients who actively prepare often develop a different mindset. They become participants in their recovery rather than passive recipients of care. This mental shift proves crucial when facing the challenges of postoperative rehabilitation.

For healthcare systems, investing in prehabilitation represents a paradigm shift from reactive treatment to proactive preparation. It acknowledges that the patient’s condition upon entering treatment significantly influences their outcomes. By strengthening patients beforehand, we’re not just improving surgical results—we’re potentially preventing the cascade of decline that often follows hospitalization.

The beauty of prehabilitation lies in its accessibility. Many exercises can be done at home with minimal equipment. Breathing exercises, gentle resistance training using body weight or light bands, and walking programs all contribute to building resilience. The key is consistency and progression tailored to individual capacity.

As our population ages and medical interventions become more complex, prehabilitation offers a practical pathway to better outcomes. It acknowledges that recovery begins before the procedure, not after. For anyone facing surgery or significant medical treatment—or caring for someone who is—exploring prehabilitation options might be one of the most important conversations to have with healthcare providers.

This approach doesn’t promise miracles, but it does offer something equally valuable: the best possible chance at maintaining independence and quality of life through challenging medical journeys.

The Psychology of Standing Again

Of all the complications that arise from deconditioning syndrome, the loss of confidence might be the most debilitating. I witnessed this profound transformation in my mother, who reached a point where she couldn’t decide what to wear each day. That erosion of self-trust represents something deeper than physical weakness—it’s a fracture in one’s sense of capability.

When confidence drains away, even the simplest decisions become monumental. The mind begins to negotiate with itself: “Maybe I shouldn’t try to stand today—what if I fall? Maybe it’s better to stay where I am.” This internal dialogue creates a self-fulfilling prophecy where fear breeds inactivity, and inactivity reinforces fear.

In my last clinical role within the NHS, I worked in a short-stay rehabilitation unit where we specialized in helping people recover after hospital stays. These individuals were, by definition, deconditioned—but more importantly, they were often apathetic and discouraged. We had excellent physiotherapists and occupational therapists, but without addressing the confidence issue, our efforts only went so far.

We learned to start by understanding each patient’s personal goals. This wasn’t about our agenda for their recovery—it was about discovering what mattered to them. Which brings me to John.

John had been a keen member of his local bowls club before a chest infection hospitalized him for nearly a month. A widower living independently with children overseas, he arrived at our unit caught between depression and determination. He wanted desperately to go home but equally desperately wanted to stay in bed where he felt safe.

During his admission assessment, John confessed that he trembled when attempting to stand and lived in constant fear of falling. “What if I fall at home and nobody finds me?” he asked. “What if I can’t cope? What if I forget how to cook or become confused?” His face showed particular sadness when he mentioned that returning to bowling seemed impossible.

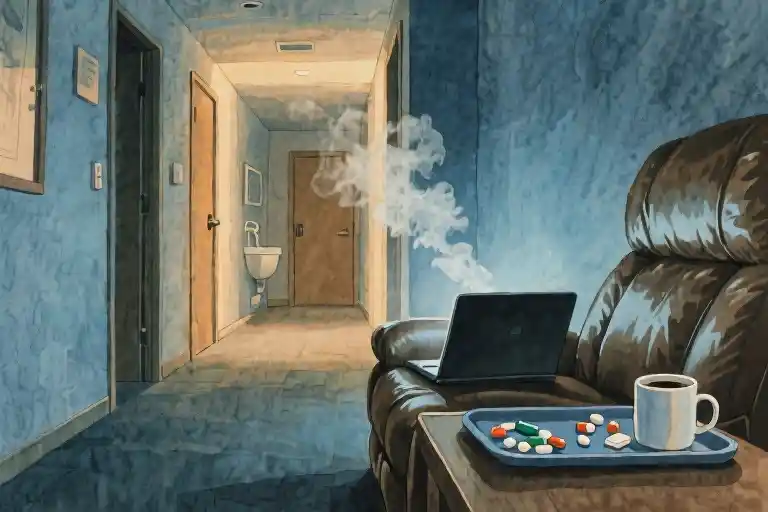

Bed represented safety. From bed, he didn’t need to make decisions. Meals arrived, nurses checked on him, and he could remain in pajamas. On better days, he might sit in his chair briefly, but bed remained his preferred sanctuary. John was experiencing what I came to call pajama-induced paralysis—that psychological state where comfortable clothing becomes a uniform of surrender.

Early in my rehabilitation work, I discovered a powerful technique: helping people access a more confident version of themselves from their past. With John, we began with the physical mechanics of standing—both hands on the chair arms, feet flat, using legs and arms to push up. But the technical approach only addressed half the problem.

The real breakthrough came when we addressed the wobble—that moment of uncertainty after standing when fear threatens to take over. For many men of John’s generation, military service provided a reference point. “Think of standing on the parade ground for inspection,” I suggested. “Stand tall like that soldier.”

Immediately, his chest lifted, and he seemed to gain three inches in height. The transformation was visible—his posture changed, but more importantly, something shifted in his eyes.

For women who had been married, we used a different cue: “Remember standing at the top of the aisle, ready to walk toward your groom.” The effect proved equally powerful. The key wasn’t the specific memory but accessing any moment of pride and accomplishment from their past.

This approach works because it bypasses the conscious fear and taps into embodied confidence. The person isn’t trying to be confident—they’re remembering a time when confidence was natural. In that moment, they become that version of themselves again.

That psychological shift creates the foundation for physical progress. When someone feels in control and stronger mentally, we can actually begin the exercise regimen with purpose. Without that confidence, exercise becomes just another reminder of limitation.

John’s journey from fearful patient to returning bowler didn’t happen overnight. But that first moment of standing tall became the reference point we returned to again and again. “Remember how you stood on that first day? That’s still in you.”

The rehabilitation of confidence often proves more challenging than physical rehabilitation because it requires confronting fears that feel entirely reasonable. The fear of falling isn’t irrational—it’s based on real risk. The art lies in acknowledging that fear while building enough confidence to move forward despite it.

What we’re really addressing is the stories people tell themselves about their capabilities. After prolonged bed rest, the story becomes “I can’t” or “It’s not safe. ” Our work involves helping them rewrite that story to include “I once could” and “I might again.”

This psychological component of deconditioning syndrome receives too little attention in standard care protocols. We measure muscle strength and mobility range, but we rarely assess confidence levels or emotional readiness. Yet without addressing the mental barriers, the physical progress remains limited.

The military stance and wedding memories represent just two approaches. Sometimes it’s about recalling professional accomplishments—the teacher remembering her classroom presence, the carpenter his steady hands guiding wood. The specific memory matters less than the emotional resonance of capability and competence.

This work requires patience and creativity. Not every memory resonates equally. Sometimes we need to try several approaches before finding the key that unlocks that confident self. But when we succeed, the results transcend the physical progress—we see people reclaim not just mobility but identity.

John eventually returned to his bowling club, though he needed a walker for stability. The greater victory wasn’t his physical recovery but the restoration of his social connections and sense of purpose. He stopped being a patient and became a bowler again—one who used a walker, but a bowler nonetheless.

That transformation begins with standing tall, both physically and psychologically. It starts with remembering who you were before the bed rest, before the illness, before the fear took hold. The body may need retraining, but the spirit needs reminding.

The Protein Equation: Fueling Muscle Recovery

While confidence provides the psychological foundation for recovery, the physical rebuilding requires something more tangible: adequate nutritional support. This is where the science of muscle synthesis meets the practicalities of daily eating habits.

Muscle tissue is fundamentally constructed from protein. When we experience periods of inactivity, the body begins breaking down muscle proteins faster than it can rebuild them. This process, known as sarcopenia, accelerates with age and becomes particularly pronounced during bed rest. The solution isn’t complicated in theory—we need to provide the building blocks for muscle repair through protein intake—but the implementation often gets lost in the challenges of appetite changes, dietary preferences, and the simple convenience of processed foods.

The mathematics of muscle maintenance are straightforward. Research suggests that older adults need approximately 1.2 to 1.5 grams of protein per kilogram of body weight daily to combat muscle loss. For someone weighing 70 kilograms (about 154 pounds), that translates to 84-105 grams of protein distributed throughout the day. The timing matters as much as the total quantity. Instead of loading protein into one large meal, spreading intake across breakfast, lunch, and dinner better supports continuous muscle protein synthesis.

Practical protein sources fall into several categories, each with particular advantages. Animal-based options include lean meats like chicken, turkey, and fish—especially fatty fish like salmon that provide anti-inflammatory omega-3 fatty acids alongside protein. Eggs offer a complete protein package with the advantage of being easily prepared in various ways. Dairy products, particularly Greek yogurt and cottage cheese, deliver both protein and calcium, which supports bone health alongside muscle maintenance.

For those preferring plant-based options or needing variety, legumes including lentils, chickpeas, and various beans provide substantial protein along with fiber. Soy products like tofu and tempeh offer complete proteins comparable to animal sources. Nuts and seeds contribute not only protein but healthy fats, though they’re calorie-dense so portion awareness is helpful.

The challenge often isn’t knowing what to eat but maintaining adequate intake when appetite diminishes or when convenience foods beckon. This is where health literacy and family education become critical. Caregivers and family members need to understand that pushing protein-rich foods isn’t just about nutrition—it’s about functional recovery. A can of tuna added to lunch, a hard-boiled egg with breakfast, a scoop of protein powder in oatmeal—these small additions accumulate throughout the day.

Beyond mere quantity, protein quality matters. Complete proteins containing all nine essential amino acids are particularly valuable for muscle synthesis. While animal products typically provide complete proteins, plant-based eaters can combine foods—rice with beans, hummus with whole grain pita—to achieve similar amino acid profiles.

Practical implementation often requires overcoming psychological barriers. When someone feels unwell, traditional “health foods” may seem unappealing. This is where creativity in food preparation becomes valuable. A protein-rich smoothie with fruit and yogurt might be more appealing than a chicken breast. Ground meat in a flavorful sauce might be easier to eat than a steak. The goal is meeting nutritional needs while respecting taste preferences and chewing capabilities, which may be compromised in recovery.

Hydration plays a supporting role in this process. Muscles are approximately 75% water, and dehydration can impede recovery and physical performance. Adequate fluid intake supports nutrient transport to muscles and helps prevent constipation—a common issue with certain protein supplements and medications.

Family education should extend beyond simple food lists to practical strategies: how to read nutrition labels for protein content, how to modify traditional recipes to boost protein, how to identify signs of inadequate intake like prolonged weakness or slow recovery. This knowledge becomes particularly important when patients return home, where professional nutritional guidance may be less accessible.

The intersection of diet and mobility creates a positive feedback loop. As protein intake supports muscle strength, improved strength enables more physical activity, which in turn stimulates greater muscle protein synthesis. Breaking the cycle of deconditioning requires addressing both sides of this equation simultaneously—movement and nutrition working in concert.

This nutritional approach isn’t about dramatic diets or expensive supplements. It’s about intentional eating patterns that recognize the increased protein needs during recovery. The simplicity of the concept—eat protein to rebuild muscle—belies the practical challenges of implementation, which is why education and support systems are essential components of successful rehabilitation.

A Call to Action: From Personal Responsibility to Systemic Change

The statistics surrounding deconditioning syndrome present a sobering reality that demands our collective attention. Approximately 40 percent of older adults will ultimately die due to complications arising from this preventable condition. Another 30 percent may recover to some degree, while the remaining 30 percent will face permanent disability that fundamentally alters their quality of life. These numbers aren’t just abstract percentages—they represent our parents, our grandparents, and eventually, ourselves.

When I sit with these figures, I find myself doing the mental math none of us want to confront. I don’t want to be part of that 70 percent who either die or become disabled from something we know how to prevent. I suspect you feel the same, not just for yourself but for those you love. This isn’t merely a medical issue; it’s a human one that calls for both personal and systemic response.

Thankfully, awareness is growing through initiatives like the ‘Sit Up, Get Dressed, Get Moving’ campaign. This isn’t about complex medical interventions but rather simple, practical actions that can make a profound difference. The philosophy is straightforward: encourage movement from the moment someone begins to feel better, maintain normal daily routines like getting dressed rather than staying in pajamas, and gradually increase activity levels in safe, supported ways.

What I appreciate about this approach is its accessibility. You don’t need special equipment or extensive training to help someone sit up straighter in bed, to encourage them to get dressed for the day, or to take those first few steps with proper support. These actions signal to both body and mind that recovery has begun, that life is waiting to be lived again rather than endured from a horizontal position.

Yet individual actions alone cannot solve this systemic problem. We must also address how our healthcare systems and cultural attitudes perpetuate the very conditions that lead to deconditioning. The tendency to default to bed rest as the primary response to illness in older adults, the lack of emphasis on prehabilitation before elective procedures, the insufficient staffing in hospitals and care homes to facilitate regular movement—these are structural issues requiring structural solutions.

Perhaps most surprisingly, this isn’t new knowledge. Medical professionals were questioning the wisdom of excessive bed rest as early as 1947. The evidence has been accumulating for decades, yet practice has been slow to change. This historical perspective reminds me that progress often comes not from discovering entirely new information but from finally deciding to act on what we’ve known for some time.

The challenge now is to translate awareness into action at every level. For families, this means having conversations with healthcare providers about mobility plans before procedures, understanding the importance of protein intake during recovery, and learning how to safely support loved ones in maintaining movement. For healthcare systems, it requires prioritizing rehabilitation services, training staff in mobility techniques, and creating environments that encourage rather than inhibit movement.

There’s something fundamentally empowering about recognizing that we don’t have to accept deconditioning as an inevitable consequence of aging or illness. The choice to sit up, to get dressed, to move—these simple acts become revolutionary in a context that has too often defaulted to passive convalescence. They represent a reclaiming of agency, a statement that life is to be participated in rather than observed from the sidelines.

As we move forward, let’s carry both the urgency of those statistics and the practicality of those simple actions. Let’s be the generation that finally takes deconditioning syndrome seriously—not just as individuals making choices for ourselves and our families, but as communities advocating for systems that support mobility and independence throughout life’s later chapters. The knowledge has been there for decades; the time to act is now.

The Choice Before Us

These numbers aren’t abstract statistics—they represent real people, real families, and real losses. The 40 percent who won’t survive deconditioning syndrome could be our parents, our partners, or eventually, ourselves. The 30 percent who recover but face permanent disability might still be among the fortunate, yet their lives will never be the same.

This isn’t just a medical issue; it’s a deeply personal one that asks something of each of us. It asks for awareness when we visit elderly relatives in care homes, noticing if they’re spending too much time in bed. It asks for advocacy within healthcare systems, questioning whether bed rest is truly necessary or simply convenient. It asks for courage to be the “bullying daughter” or “determined son” who insists on movement even when it feels uncomfortable.

My mother’s final months taught me that dignity isn’t found in passive comfort but in maintained capability. Her brief moments of standing, of choosing her own clothes, of wheeling herself to the sitting room—these were victories not just against infection but against the slow erosion of self.

What’s remarkable isn’t that we’re facing this challenge now, but that we’ve known about it for generations. Since 1947, forward-thinking medical professionals have been questioning the dogma of prolonged bed rest. The knowledge has been available, yet implementation lags behind understanding. This gap between knowing and doing is where we lose ground, where muscles weaken and confidence fades.

The solution begins not with grand systemic changes but with simple daily decisions: choosing to sit up rather than lie down, to get dressed rather than remain in pajamas, to take those few steps to the chair rather than wait for assistance. These small acts of defiance against decline accumulate into meaningful difference.

Campaigns like “Sit Up, Get Dressed, Get Moving” provide the framework, but the commitment must come from individuals—both those at risk of deconditioning and those who care for them. It requires changing our perception of what constitutes “good care,” recognizing that sometimes the kindest action isn’t allowing rest but encouraging activity.

History shows us that medical understanding evolves, sometimes painfully slowly. The recognition that bed rest could be harmful rather than healing took decades to gain traction. Now we stand at another inflection point, where we must move beyond mere recognition to active prevention.

The choice isn’t between doing everything and doing nothing—it’s between starting somewhere and starting nowhere. Between accepting decline and challenging it. Between being part of the 70 percent who suffer from deconditioning syndrome or joining the 30 percent who overcome it.

This isn’t about achieving perfect health in old age—that may be beyond our control. It’s about maintaining what function we can for as long as we can. It’s about recognizing that while we can’t always choose our health circumstances, we can choose how we respond to them.

The work continues, both in healthcare systems and around kitchen tables. The conversation needs to move from medical journals to family discussions, from clinical settings to community centers. What began as a challenge to conventional wisdom in 1947 must now become conventional practice in our homes and hospitals.

Our parents’ generation might have accepted decline as inevitable, but we know better. We have the knowledge, we have the strategies, and we have the opportunity to write a different story—one where aging doesn’t necessarily mean diminishing, where recovery remains possible even in late life, where the end of one’s story isn’t predetermined by time spent in bed.

The final chapter of this struggle hasn’t been written yet. How it ends depends on what we choose to do today.