The year was 1974. A lanky 19-year-old with shaved head and Indian robes wandered the streets of Los Altos, California, fresh off a soul-searching trip to India. By day, he crashed on friends’ couches; by night, he worked the graveyard shift at Atari fixing circuit boards. To most observers, Steve Jobs looked like just another dropout hippie – the kind you’d expect to find selling handmade jewelry on Haight Street, not building a tech empire.

Yet beneath the unconventional exterior brewed something extraordinary. That summer, while his Harvard-educated peers like Bill Gates were writing code in air-conditioned labs, Jobs was developing something far more valuable: the art of seeing what others missed. His time in India had stripped away conventional thinking, while the Atari night shifts gave him front-row seats to how ordinary people interacted with technology.

This perfect storm of apparent chaos – the dropout status, the Eastern philosophy phase, the menial tech job – was quietly forging one of business history’s most disruptive minds. The very qualities that made him seem like a failure to the establishment would soon become his superpowers: outsider perspective, hunger for simplicity, and willingness to question everything.

What few understood then (and many still miss today) is that true innovation often emerges from such messy beginnings. The circuit boards Jobs repaired at Atari weren’t just technical puzzles; they were windows into how real users struggled with complexity. The meditation practices he brought back from India weren’t mere spiritual affectations – they were training in stripping ideas down to their essence. Even the famous Reed College calligraphy class he audited after dropping out, often framed as a random detour, was sharpening his eye for design that would later define Apple products.

The stage was set for one of technology’s great eureka moments. All it would take was a basement meeting of hobbyists, a brilliant engineer named Woz, and that peculiar Jobsian ability to spot the elegant solution hiding in plain sight. But that’s getting ahead of our story…

The Chaotic Youth: Failure or Keen Observer?

The story of Steve Jobs in his early twenties reads more like a counterculture manifesto than a business origin story. Here was a college dropout working night shifts at Atari, who abruptly quit to wander through India, returning with a shaved head and flowing Indian garments. To the casual observer in 1974, this looked less like the makings of a tech visionary and more like another lost soul of the post-hippie era.

But beneath the surface of what society might label as ‘failure’ lay crucial formative experiences. Jobs’ decision to leave Reed College wasn’t about rejecting education, but rather resisting what he called ‘the empty calories’ of mandatory courses that lacked practical application. In his own words from a later interview: ‘I didn’t see the value in spending my father’s life savings on classes that wouldn’t help me answer the questions I cared about.’

His subsequent journey to India planted seeds that would later blossom into Apple’s design philosophy. While contemporaries like Bill Gates were building technical mastery at Harvard, Jobs was developing something equally valuable – a perspective. The seven months spent traveling with practically nothing taught him unexpected lessons about minimalism. Not the aesthetic kind, but the brutal functionality of having only what truly matters. He carried this insight home in his backpack alongside his well-thumbed copy of ‘Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance.’

The Atari night shift job, often dismissed as just another dead-end gig, became an unlikely classroom. Working alongside engineers who spoke in technical jargon, Jobs noticed how actual players interacted with the games differently than their creators intended. This front-row seat to the disconnect between makers and users would later inform Apple’s obsessive focus on intuitive design. Those late nights troubleshooting arcade machines gave him something no business school could teach – an understanding of how ordinary people actually use technology when no one’s there to explain it to them.

What looked like a series of false starts to outsiders were actually the pieces coming together. The dropout phase cultivated independent thinking. The India experience sharpened his eye for essentialism. The Atari job developed user empathy. The puzzle wasn’t complete yet, but the border pieces were in place. All he needed was the right catalyst to snap them into focus – which would come from an unexpected gathering of hobbyists in a suburban garage.

The Birth of an Opportunity: Spotting the ‘Less is More’ Demand

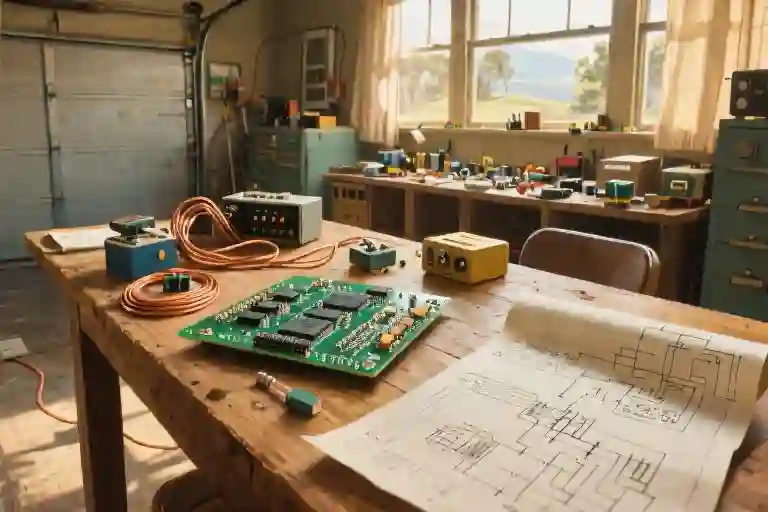

The Homebrew Computer Club meetings in 1975 weren’t exactly glamorous affairs. Held in a Menlo Park garage, these gatherings brought together hobbyists who shared one obsession: building computers from scratch. Most attendees arrived with grease-stained notebooks and boxes of electronic components, ready to debate circuit designs late into the night. Among them stood a barefoot, 20-year-old Steve Jobs, looking more like a wandering mystic than a future tech titan.

What separated Jobs from the other enthusiasts wasn’t technical expertise – his friend Steve Wozniak far surpassed him there. It was his ability to notice what people weren’t saying. While engineers proudly showcased their complex motherboard designs requiring hundreds of hand-soldered connections, Jobs observed the quiet frustration of amateurs struggling to assemble them. The real innovation opportunity, he realized, wasn’t in creating more sophisticated components, but in eliminating unnecessary complexity.

This insight came into sharp focus during one particular meeting when a club member threw his unfinished kit across the room in frustration. “I just want the damn thing to work,” he muttered, “not spend six months becoming an electrical engineer.” That moment crystallized Jobs’ realization: the DIY computer movement’s pain point wasn’t a lack of technology, but too much of it. Most hobbyists didn’t crave the assembly process itself – they tolerated it as the only path to owning a personal computer.

Jobs’ proposed solution was characteristically simple: pre-assembled circuit boards that retained just enough DIY elements to feel authentic while removing the most tedious technical hurdles. Where others saw computer building as an all-or-nothing proposition, he recognized a spectrum of technical willingness among enthusiasts. This segmentation thinking would later become Apple’s hallmark, from the Macintosh’s “computer for the rest of us” positioning to the iPhone’s intuitive interface.

The partnership with Wozniak proved crucial in executing this vision. While Jobs identified the market gap, Wozniak possessed the engineering prowess to design an elegantly simple printed circuit board. Their skills formed perfect complements – Wozniak could obsess over elegant technical solutions while Jobs focused on stripping away anything that didn’t serve the user’s core need. This dynamic foreshadowed Apple’s future product development philosophy, where groundbreaking technology only mattered if it disappeared into effortless user experience.

What made this insight revolutionary wasn’t just spotting an underserved niche, but recognizing that simplification itself could be a premium offering. While competitors assumed computer enthusiasts wanted maximum configurability, Jobs understood many would pay more for carefully curated limitations. This counterintuitive approach – charging a premium to do less – would later define Apple’s entire business model, from the unibody MacBooks to the app store’s walled garden.

The Homebrew Club’s significance in tech history wasn’t the groundbreaking hardware produced there, but the commercial mindset Jobs developed observing its members. He didn’t just see hobbyists – he recognized proto-consumers struggling with products designed by engineers for engineers. This user-first perspective, more than any technical contribution, set the foundation for Apple’s future successes. The real innovation wasn’t in the circuit board design, but in realizing technology only matters when it serves human needs rather than technical ideals.

The First Fortune: Business Secrets Hidden in Circuit Boards

Most people remember Steve Jobs as the visionary who gave us the iPhone, but few know how he made his first dollar in tech. It wasn’t through sleek devices or marketing genius – it began with a simple printed circuit board that solved a very specific problem for computer hobbyists.

The breakthrough came from understanding two fundamental principles: what people actually needed (not just what they said they wanted), and how to deliver it at the right price point. While other companies were selling complex computer kits requiring hundreds of solder connections, Jobs noticed most enthusiasts just wanted the core functionality – a working circuit board that could run basic programs.

Cost Structure: The Art of Strategic Compromise

Jobs and Wozniak’s initial design used off-the-shelf components whenever possible. The MOS 6502 microprocessor ($25), DRAM chips ($5 each), and other standard parts kept material costs at $25 per board. This decision reflected Jobs’ emerging philosophy: perfect was the enemy of good enough. Rather than custom-designing components (which would have increased costs and development time), they worked with what the market already offered.

The real cost innovation came in labor. Wozniak handled the design work pro bono, while Jobs negotiated free workspace at a friend’s garage. Their only upfront expenses were:

- $1,500 for initial PCB fabrication

- $1,000 for components for the first 100 units

This lean approach meant they could start generating revenue with less than $2,500 in capital – about $13,000 in today’s dollars when adjusted for inflation.

Pricing Strategy: Psychology Over Math

At $50 per board, the Apple I carried a 100% markup – aggressive by electronics standards at the time. But Jobs understood three psychological factors that justified the price:

- Value comparison: Competing kits like the Altair 8800 cost $439 ($2,300 today) but required assembly

- Perceived expertise: The higher price positioned their product as premium within the hobbyist community

- Future-proofing: The margin allowed for inevitable production hiccups

Interestingly, they nearly priced at $666.67 to reference Wozniak’s favorite repeating numbers, but settled on $500 for complete systems – showing how even in their first venture, business realities tempered technical whimsy.

Profit Calculation: Making the Numbers Dance

The initial business plan projected:

Revenue: 100 boards × $50 = $5,000

Costs: $1,500 (design) + $2,500 (materials) = $4,000

Profit: $1,000 (20% margin)In reality, their first order to Paul Terrell’s Byte Shop for 50 units at $500 each (fully assembled) delivered much stronger results:

- Actual revenue: $25,000

- Actual costs: ~$12,000

- Actual profit: $13,000 (52% margin)

The variance came from two smart adjustments:

- Bulk purchasing reduced per-unit component costs

- Assembly services created an upsell opportunity

This early experience cemented Jobs’ belief in premium pricing – not as greed, but as necessary fuel for innovation. The extra margin allowed them to fund Apple II development, which would eventually sell over 6 million units.

What modern entrepreneurs often miss is how deliberately unimpressive these beginnings were. The Apple I wasn’t technologically revolutionary – Wozniak himself called it just another ‘dumb terminal.’ The magic came from recognizing an underserved niche and serving it with ruthless efficiency. Sometimes the best business ideas aren’t about creating something new, but removing unnecessary complexity from what already exists.

The Blueprint Hidden in Circuit Boards

What made Jobs’ first business venture remarkable wasn’t the technology—it was how he spotted an invisible pattern in human behavior. While other tech enthusiasts marveled at complex DIY computer kits requiring 200+ solder points, Jobs noticed something more telling: the frustrated sighs, the half-finished projects collecting dust, the enthusiasts who just wanted their creations to work without becoming electrical engineers overnight. This observation became the cornerstone of three replicable principles for modern entrepreneurship.

Mining Gold from Compromise

Every market niche has its quiet concessions—those moments when users mutter ‘I guess this will do’ while wrestling with cumbersome products. Jobs identified this universal truth when he saw Homebrew Computer Club members tolerating absurdly complex kits. His insight? People’s willingness to endure inconvenience often signals untapped opportunity. The methodology is deceptively simple:

- Watch for workarounds (like using pre-made components to avoid soldering)

- Note recurring complaints (‘I spent three weekends just getting the memory to work’)

- Spot the delta between current solutions and actual needs

This approach transcends tech. Airbnb recognized travelers compromising on hotel prices, Uber saw people reluctantly accepting taxi hassles—both found billion-dollar opportunities in everyday frustrations.

The Original MVP Playbook

Before ‘minimum viable product’ became startup gospel, Jobs and Wozniak were practicing its purest form. Their initial circuit boards weren’t fancy—just functional enough to let hobbyists skip the most tedious steps. This stripped-down approach revealed key MVP lessons:

- Test with real transactions: Selling 50 units upfront proved demand beyond theoretical interest

- Preserve iteration space: Simple designs allowed quick modifications based on user feedback

- Limit upfront costs: Using off-the-shelf parts kept initial investment under $1,500

Modern parallels abound. Dropbox’s early demo video, Zappos’ initial shoe sales from local stores—all follow this same principle of validating demand with the least possible effort.

The Yin-Yang Partnership Principle

Perhaps Jobs’ most overlooked genius was recognizing exactly what he lacked. Wozniak wasn’t just a technical wizard—he was Jobs’ perfect counterbalance. Their partnership blueprint offers a checklist for finding complementary co-founders:

| Your Strengths | Ideal Partner’s Traits |

|---|---|

| Big-picture vision | Detail-oriented execution |

| Market intuition | Technical depth |

| Risk tolerance | Practical constraints |

This dynamic explains why some founder pairs thrive while others combust. Google’s Page (engineer) and Brin (visionary), Microsoft’s Gates (coder) and Allen (strategist)—the pattern persists across tech history. The magic happens when partners speak enough of each other’s language to collaborate, but bring fundamentally different lenses to problems.

These principles form a timeless framework, whether you’re building circuit boards or mobile apps. The real breakthrough isn’t in the idea itself, but in recognizing that the most powerful opportunities often hide in plain sight—disguised as minor annoyances everyone else has learned to live with.

The Checklist for Spotting Minimalist Opportunities

That first circuit board Steve Jobs sold wasn’t just a product—it was a lens for seeing the world differently. The same principles that guided his early entrepreneurship can help anyone identify overlooked opportunities in their daily environment.

The Compromise Detector

Jobs noticed computer enthusiasts tolerating unnecessary complexity because no better option existed. This pattern repeats everywhere:

- What tasks do people complete with visible frustration?

- Where do hobbyists use duct-tape solutions for professional needs?

- What “normal inconveniences” has everyone accepted as unavoidable?

Keep a small notebook to document these observations. The most promising opportunities often hide in behaviors people themselves don’t question.

The 80/20 Filter

The original Apple I succeeded by focusing on the 20% of features that delivered 80% of the value. Apply this lens to potential ideas by asking:

- What’s the simplest version that would still solve the core problem?

- Which features are only there because “that’s how it’s always been done”?

- Can we remove more than we add?

The Partnership Matrix

Jobs brought vision, Wozniak brought technical skills. Effective collaborations often pair opposites:

[ ] The Dreamer (big ideas, weak on details)

[ ] The Architect (systematic thinking, risk-averse)

[ ] The Hustler (sales and execution focus)

[ ] The Craftsman (quality-obsessed, slower pace)Circle your dominant trait, then actively seek partners who check different boxes.

The Validation Playbook

Before investing significant resources, test assumptions as Jobs did with his $50 boards:

- Conversation tests: “Would you buy [solution] for [price]?” (Watch for genuine excitement vs. polite interest)

- Proxy metrics: If making physical products, measure interest through pre-orders or waiting lists

- Shadow prototyping: Create mockups using existing tools (e.g., manual processes pretending to be automated)

The Reality Check

Finally, ask the hard questions Jobs faced in that Atari break room:

- Is this something people would pay for, or just a cool idea?

- Can the first version be built with existing skills/resources?

- What’s the smallest possible proof of concept?

Opportunities don’t announce themselves with flashing signs. They whisper in the gaps between what exists and what could be—in the sighs of people adapting to clumsy solutions, in the extra steps everyone takes without thinking. The next revolutionary product might start as someone noticing an ordinary inconvenience and refusing to accept it as inevitable.