The email arrived on a Tuesday morning, the kind of bureaucratic rejection that changes lives with a few keystrokes. A 19-year-old Kurdish student in Turkey—top of her class, perfect test scores—had been denied university admission under a policy that effectively quotas minority enrollments. Her official rejection letter cited ‘administrative reasons,’ but everyone knew the truth. This happened in 2023, not 1923. Seventy-five years after the Universal Declaration of Human Rights declared education a universal right “without distinction of any kind.”

Globally, only 17% of countries fully comply with Article 2’s equality principle according to Human Rights Watch’s latest compliance report. We’ve created a peculiar dissonance in our world: more human rights laws exist than ever before, while systemic discrimination evolves new disguises. The gap between legal poetry and lived reality isn’t just frustrating—it reveals something fundamental about how power negotiates with morality.

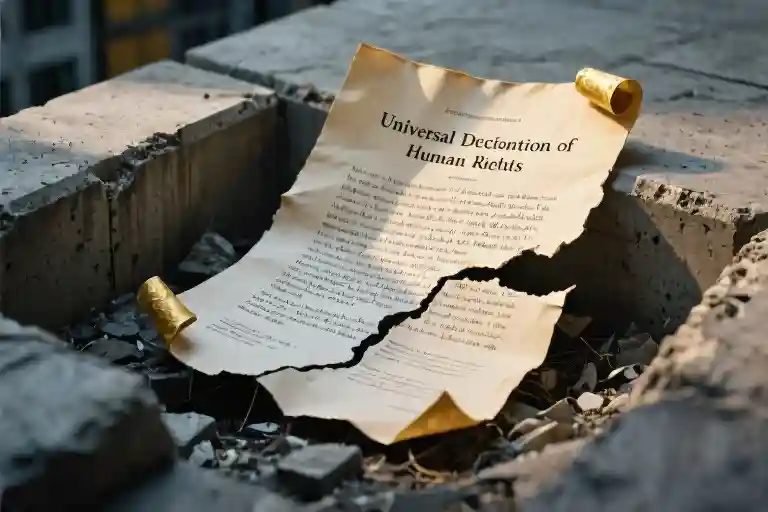

Take that Declaration document itself. Drafted in 1948’s postwar idealism, its 30 articles read like a recipe for human dignity: equality before the law (Article 7), freedom from arbitrary arrest (Article 9), the right to rest and leisure (Article 24). Noble aspirations all, beautifully typeset on United Nations parchment. Then you compare it to last month’s headlines—migrant children separated at borders, journalists jailed for criticizing leaders, women barred from stadiums—and the disconnect becomes almost surreal. Not because the Declaration is flawed, but because its most signatory nations treat it like architectural renderings for a building they never intend to construct.

This paradox defines modern human rights work. We don’t lack the blueprints; we lack the political will to follow them. When governments celebrate their human rights commitments during UN review sessions while simultaneously dismantling protections domestically, they’re engaging in a form of legal doublespeak. The student in Turkey experienced this firsthand—her country ratified the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, then created loopholes through local policies.

What makes this especially infuriating isn’t the outright refusal of rights (though that exists), but the sophisticated pretense of compliance. Modern discrimination rarely announces itself with burning crosses or ‘Whites Only’ signs. It wears bureaucratic camouflage—zoning laws that coincidentally displace minority communities, voter ID requirements that disproportionately affect certain groups, school admissions criteria that privilege particular dialects. All technically legal. All violating the spirit of that 1948 Declaration.

The most pernicious myth isn’t that human rights don’t exist, but that parchment promises equate to lived reality. Like showing a starving person a menu and calling it a meal. Until we confront this gap—between rights declared and rights experienced—we’ll keep drafting magnificent documents that change little beyond library catalogues.

The Promised World: When Ideals Took Shape

The year was 1948. The stench of concentration camps still lingered in European air, while colonial empires crumbled across Asia and Africa. In this landscape of collective trauma and cautious hope, a group of diplomats gathered in Paris to draft what Eleanor Roosevelt called “a Magna Carta for all humanity.” The Universal Declaration of Human Rights emerged not as a legally binding treaty, but as something more profound—a shared vision of what our species could become.

Reading Article 2 today still gives me chills: “Everyone is entitled to all the rights… without distinction of any kind.” The drafters knew they were crafting poetry in legal form. That semicolon between “race” and “colour” contains multitudes—an acknowledgment that humanity’s divisions run deep, but our entitlements run deeper. The document’s genius lies in its simplicity. No convoluted legalese, just 30 articles stating plainly that food, safety, and dignity aren’t privileges but birthrights.

Yet from the beginning, the cracks showed. The Soviet bloc abstained, fearing Western individualism would undermine collective socialism. South Africa resisted, unwilling to confront its apartheid system. Saudi Arabia objected to equality in marriage rights. These reservations foreshadowed what we now know: declarations don’t change realities; people do.

The enforcement mechanism was always the Declaration’s open secret. Unlike the Geneva Conventions with their protocols for prosecution, the UDHR relies on what lawyers call opinio juris—the belief that certain standards should be law. It’s a beautiful notion: that repeated recognition might crystallize into obligation. But as any activist can tell you, “should” and “shall” live in different neighborhoods. The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights later added teeth in 1976, yet compliance remains stubbornly voluntary.

What fascinates me most isn’t the document’s limitations, but its radical premise: that a garment worker in Bangladesh and a tech CEO in Silicon Valley share fundamental entitlements. This leveling vision still feels revolutionary seventy-five years later. The drafters planted a seed in the global consciousness—one that grows each time protesters chant “Black Lives Matter” or women demand equal pay. The Declaration didn’t create rights; it named what people already knew in their bones to be true.

Perhaps its greatest power lies in being quotable. I’ve seen Article 3 (“Everyone has the right to life, liberty and security”) spray-painted on refugee camp walls, and Article 23’s fair wage demands waved on picket signs. These words became tools ordinary people could wield, unmediated by lawyers or politicians. That’s the paradox we grapple with: a non-binding document that became the moral yardstick by which nations are measured.

Legal scholars will tell you about jus cogens norms and customary international law. But in hospital wards where patients are turned away for being undocumented, in classrooms where girls are told science isn’t for them, the real question persists: How do we make these magnificent words walk off the page and into people’s lives? The answer, it seems, begins by recognizing that declarations don’t fulfill themselves—they demand our hands to give them weight.

The Cracks Beneath the Articles

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights reads like poetry. Article 7 promises freedom from discrimination. Article 16 guarantees equal marriage rights. Article 26 declares education a universal entitlement. These words glow with moral clarity—until you hold them against the light of reality, where they fracture into a thousand contradictions.

When Rights Collide with Reality

In Minneapolis, a police officer kneels on a Black man’s neck for nine minutes. The city’s own policy manual prohibits neck restraints, yet the 2020 killing of George Floyd became the 1,276th documented case of police violence against African Americans that year. Meanwhile, Article 7 of the Declaration states plainly: “All are equal before the law.” The disconnect isn’t academic—it’s measured in body counts. The Washington Post’s database shows racial minorities experience police violence at 2.5 times the rate of white Americans, despite constituting only 39% of the population.

Saudi Arabia presents another paradox. The Kingdom ratified the Declaration in 1948, including Article 16’s guarantee of “equal rights as to marriage.” Yet until 2019, Saudi women needed male guardian approval to obtain passports or travel abroad. The much-touted 2022 Personal Status Law still requires women to obtain guardian consent for marriage contracts. When human rights become negotiable, the Declaration’s promises turn to vapor.

Education statistics from Brazil’s favelas reveal a quieter violence. Article 26 promises free elementary education for all, but UNESCO data shows only 68% of Brazilian youth complete secondary school—a figure that plummets to 41% in low-income neighborhoods. In Rio’s Complexo do Alemão, public schools average 35 students per teacher, triple the UN-recommended ratio. Rights without infrastructure become cruel taunts.

The Paper Shield

Governments wield the Declaration like a prop—quoted in speeches, engraved in courthouses, then ignored in policy rooms. The U.S. State Department’s 2022 Human Rights Report condemned Iran’s suppression of protests while American cities deployed tear gas against Black Lives Matter demonstrators. Saudi Arabia hosts UN human rights forums in Riyadh’s glittering conference centers as activists like Loujain al-Hathloul remain banned from travel. Brazil’s constitution mirrors Article 26’s education guarantees even as schools in indigenous territories lack running water.

This hypocrisy follows a pattern:

- Symbolic Adoption: Countries ratify treaties for international credibility

- Selective Implementation: Apply rights only when politically convenient

- Creative Noncompliance: Develop loopholes (“local customs,” “resource limitations”)

- Defensive Posturing: Attack critics rather than address violations

The gap between rights and reality isn’t accidental—it’s engineered. When the UN reviewed Saudi Arabia’s human rights record in 2023, the Kingdom received 348 recommendations. It accepted just 60%—rejecting all gender equality proposals. The math is telling: rights cost political capital, while repression pays dividends.

Measuring the Distance

Quantifying these gaps reveals their absurdity:

- Police Violence: Black Americans are 3.23x more likely to be killed by police than whites (Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health)

- Guardianship Laws: 23 countries still require male approval for women’s travel (World Bank Women, Business and the Law Report)

- Education Deficit: 244 million children worldwide lack school access—despite Article 26 (UNESCO)

These aren’t policy failures. They’re policy choices. When Minneapolis paid $27 million to George Floyd’s family while resisting police union reforms, it revealed priorities. When Saudi Arabia spends $1 billion on NEOM’s futuristic city while maintaining guardianship rules, it makes values clear. The Declaration’s words mean nothing until they’re budget line items.

The Human Cost

Behind every statistic are faces. There’s 16-year-old João Pedro, shot by Brazilian police during a 2020 raid on his favela home—a child Article 26 promised an education. There’s Salma, a Saudi nurse who lost her hospital job when her guardian refused to renew her work permit—a professional Article 23 promised the right to employment. There’s Philando Castile, legally carrying a firearm when Minnesota police fired seven bullets into his car—a citizen Article 3 promised “life and liberty.”

Rights on paper feel abstract until you’re the one they deny. The Declaration’s power doesn’t come from its parchment—it comes from our willingness to make governments sweat when they violate it. That’s the dirty secret: these rights only exist when we force them into existence. The rest is calligraphy.

The Trap of Paper Rights

There’s something deeply unsettling about watching governments celebrate human rights declarations while systematically violating them. The disconnect isn’t accidental—it’s structural. Three fundamental forces maintain the gap between rights on paper and rights in practice: political convenience, economic calculations, and cultural resistance.

Sovereignty as a Shield

China’s persistent citation of ‘non-interference in internal affairs’ when questioned about Uyghur treatment reveals how political systems weaponize sovereignty. Similarly, the U.S. condemns human rights abuses abroad while resisting international scrutiny of its police brutality rates. This selective compliance isn’t hypocrisy—it’s strategy. States uphold rights only when politically expedient, treating the Universal Declaration as a menu rather than a binding contract. The recent UN Human Rights Council report (2023) shows 68% of violations occur under ‘domestic jurisdiction’ claims.

The Cost of Compassion

South Africa’s Constitutional Court mandated adequate housing in 2000’s Grootboom case, yet 2.3 million still live in shacks. Why? Budgets prioritize military spending over social rights. Harvard’s Rights vs Resources study (2021) found implementing economic rights requires redirecting 12-18% of GDP—politically toxic in austerity-driven economies. When Finland introduced legally enforceable housing rights, it required raising top-tier taxes by 4%. The lesson? Rights without funding are poetry.

Culture as Contested Ground

Iran’s morality police enforcing hijab laws despite Article 18’s religious freedom protections illustrates how cultural narratives override legal commitments. Local traditions often reinterpret universal rights—sometimes productively (Kenya’s community-based land rights), sometimes oppressively (India’s caste-based discrimination persisting despite constitutional bans). The tension isn’t East vs West; France’s secularism laws contradict cultural rights protections too. As anthropologist Mahmood Mamdani notes, ‘Human rights become hegemonic when they speak in universal tongues but local accents.’

What emerges isn’t a conspiracy against rights, but a sobering reality: declarations create moral standards, not mechanical obligations. The trap snaps shut when we mistake their aspirational language for self-executing guarantees. Rights live not in parchment, but in the messy, expensive, culturally specific work of enforcement—precisely where most states lose interest.

From Declaration to Action

The gap between human rights on paper and rights in practice isn’t inevitable. Some cracks in the system have been successfully filled – not with more declarations, but with concrete mechanisms that turn lofty principles into lived reality. Three distinct approaches show how declarations can evolve from aspirational documents to operational frameworks.

Constitutional Alchemy: Norway’s Experiment

Norway did something radical in 2014 – they baked the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights directly into their constitution. This wasn’t symbolic adoption but surgical integration. The revised Article 110 now requires all new legislation undergo mandatory human rights compliance checks, similar to environmental impact assessments. Parliamentary committees must answer one piercing question: “How does this bill advance or hinder our treaty obligations?”

The results? When Oslo proposed austerity measures in 2018, the Human Rights Impact Assessment flagged disproportionate harm to Sami communities’ cultural rights. The final package included targeted protections for reindeer herding subsidies. What makes Norway’s model replicable isn’t their wealth (many rich nations don’t do this) but their procedural innovation – creating institutional speed bumps that force policymakers to engage with rights frameworks.

Grassroots Monitoring: Mexico’s Barefoot Auditors

In Mexico City’s Iztapalapa district, grandmothers with clipboards have become unlikely human rights enforcers. The “Observatorio de Derechos Humanos” trains community members to document rights violations using simplified versions of UN monitoring protocols. Their secret weapon? Turning abstract rights into neighborhood-level metrics. Article 25’s right to adequate housing becomes measurable through:

- Days without running water

- Distance to nearest health clinic

- Percentage of homes with proper flooring

These citizen-generated reports now directly feed into Mexico City’s human rights dashboard. When data showed 68% of evictions violated due process standards, the district attorney’s office established special eviction review panels. The lesson? Communities don’t need law degrees to hold power accountable – just the right tools to translate rights into observable facts.

The Gambia Gambit: Small Country, Big Leverage

When Gambia filed a case against Myanmar at the International Court of Justice in 2019 alleging genocide against Rohingya Muslims, it revealed a hidden strength in the international system. The case utilized Article IX of the Genocide Convention, which allows any signatory state to bring complaints against another – regardless of direct involvement. This created legal ripple effects:

- Forced Myanmar to participate in ICJ proceedings

- Triggered parallel investigations at the ICC

- Enabled third-party states to submit supporting evidence

Though Gambia had no geopolitical stake in Myanmar, its action demonstrated how smaller nations can activate dormant enforcement mechanisms. The case continues, but already compelled Myanmar to implement provisional measures – proving that creative use of existing frameworks can achieve what decades of UN resolutions couldn’t.

These examples share a common thread: they treat declarations not as endpoints but as toolkits. Norway shows how to institutionalize rights thinking, Mexico demonstrates community-powered monitoring, and Gambia reveals the untapped potential of collective enforcement. The path forward isn’t more declarations, but smarter ways to make existing ones breathe.

Next steps for readers:

- Research if your country has human rights impact assessment laws

- Download UN’s “My Rights My Voice” community monitoring toolkit

- Support organizations like Justice Rapid Response that help small states pursue international cases

From Words to Action: Making Rights Real

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights turns 75 this year, yet its promises remain unfulfilled for millions. This disconnect between legal frameworks and lived experience isn’t just frustrating—it’s dangerous. When rights exist only in documents, they become privileges reserved for those with power to claim them.

Three Ways to Bridge the Gap

- Demand Transparency

Every national government reporting to the UN Human Rights Council must submit compliance reviews. These dry bureaucratic documents contain goldmines of information. Find your country’s latest report through OHCHR’s database, then cross-reference with local NGO assessments. The discrepancies tell the real story. - Support Ground-Level Monitoring

Organizations like Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International rely on decentralized verification networks. In Rwanda, women’s groups used simple smartphone documentation to expose gaps in gender quota implementations. You don’t need to be a lawyer—just download witness reporting apps like EyeWitness or TrialWatch. - Leverage Consumer Power

The 2013 Bangladesh garment factory collapse proved supply chains could enforce change faster than treaties. Apps like Buycott now let you scan products to check corporate human rights records. When 15,000 EU citizens switched banks over fossil fuel investments last quarter, it wasn’t charity—it was accountability.

The Rwanda Experiment

Post-genocide Rwanda faced a paradox: constitutional gender equality provisions versus entrenched patriarchal norms. Their solution? Mandatory 30% female representation in all decision-making bodies, from village councils to corporate boards. Critics called it tokenism—until maternal mortality rates dropped 60% in a decade. Sometimes the bluntest tools work best.

The Intergenerational Question

My grandmother marched for voting rights she never fully enjoyed. My mother fought for workplace protections still being litigated today. As I watch students rally for climate justice, I wonder: will my grandchildren still be parsing Article 25’s right to “adequate living standards” in 2098? The declaration was never meant to be a ceiling—just the floor we’re still struggling to reach.