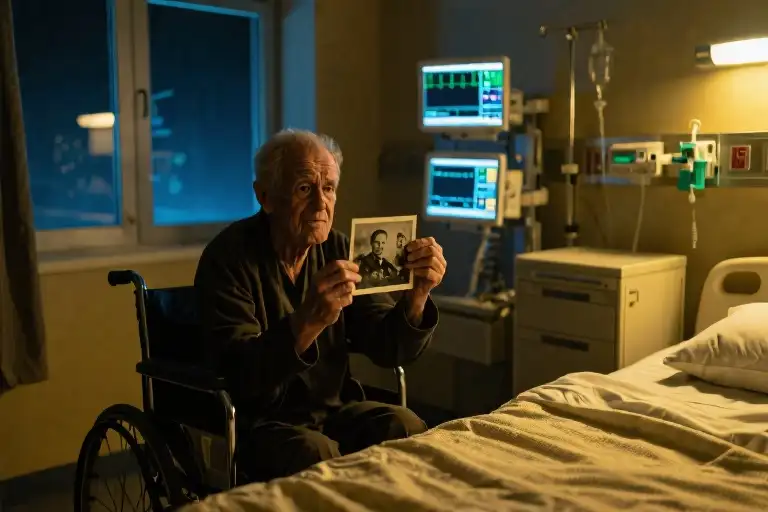

The dim glow of the night light cast elongated shadows across the hospital room as I entered for final rounds. A raspy voice cut through the rhythmic beeping of monitors: “Hey, Doc, aren’t you headed home?” There, nearly swallowed by a fortress of pillows, lay my patient – a 90-year-old Missouri native with advanced lung cancer, his oxygen tubing tracing silver lines against paper-thin skin. As an oncologist specializing in hospice and palliative care, these twilight conversations during my weekly hospital service rotations at Mayo Clinic often became unexpected gifts.

His skeletal frame seemed to sink deeper into the mattress with each shallow breath, yet his eyes held the alertness of a man with stories still to tell. The IV pump whirred softly beside us, its morphine drip keeping pace with his pain while I adjusted my stool to his eye level. In end-of-life care, such moments carry weight beyond medical charts – they become sacred spaces where history breathes through cracked lips and trembling hands.

“You know I was with the engineers on those islands in the Pacific,” he began during a lull between coughing spells, his voice gaining strength as memory overtook weakness. The war stories that followed weren’t the battlefront heroics we see in films, but raw accounts of teenagers building hangars and sewer systems on forgotten atolls. His gnarled fingers, now struggling to lift a water cup, had once swung hammers that shaped runways for B-29s. That contrast – between the vigorous young soldier in his recollections and the frail man before me – hung in the antiseptic air like unspoken poetry about time’s passage.

What struck me most wasn’t just his wartime service, but the prophetic clarity with which this dying man had viewed postwar America from his Pacific outpost. Between adjusting his oxygen flow and noting his vitals, I caught glimpses of a mind that had anticipated the housing boom and baby boom before either had names. These weren’t just memories; they were living testaments to how ordinary people witness extraordinary chapters of history – chapters now fading with each labored breath in Room 423.

The night shift’s quiet intimacy allowed what daytime’s clinical bustle often prevents: true listening. Beyond managing symptoms and updating charts, these hours revealed why palliative care demands slowing down enough to hear the human stories beneath the diagnoses. As his voice wove between 1944 and the present, between construction blueprints and hospital bedding, I realized how much medical training prepares us to treat diseases but often fails to teach us how to honor the full lives those diseases threaten to eclipse.

The Weight of a Question

The fluorescent lights hummed softly overhead as I paused at the doorway of Room 427. A faint glow from the night light cast elongated shadows across the hospital bed, where a small figure lay nearly swallowed by pillows. His oxygen cannula traced a pale line across sunken cheeks, rising and falling with each shallow breath.

‘Hey, Doc, aren’t you headed home?’ The question caught me mid-chart review. His voice carried the gravelly texture I’d come to recognize in my thirty years of oncology and palliative care practice – that particular blend of fatigue and resilience unique to those navigating life’s final chapters.

I pulled up a chair, its metal legs scraping against the linoleum. At ninety years old with stage IV lung cancer, this Missouri native had every reason to focus on his own discomfort. Yet here he was, noticing my 14-hour shift, worrying about when I’d eat dinner. Such moments often held more diagnostic value than any lab report in our electronic medical records.

His hands trembled as he adjusted the nasal tubing, fingers still bearing the calluses of a lifetime working construction. Between wet, rattling coughs that shook his narrow frame, he’d fix me with startlingly clear blue eyes. The pauses grew longer after each coughing spell, yet his determination to speak never wavered.

Then came the pivot point – those seven words that transformed a routine check-in into something far more profound: ‘You know I was with the engineers…’

Suddenly we weren’t just doctor and patient in a Rochester hospital room. We were time travelers, about to embark on a journey to coral atolls in the Pacific where young men poured concrete under enemy fire. The beeping IV pump became the distant echo of artillery. The scent of antiseptic blended with imagined salt spray.

In palliative care, we’re trained to recognize these threshold moments – when a person shifts from discussing symptoms to sharing legacy. Research shows that such life review improves end-of-life quality measures more than any medication adjustment. Yet our reimbursement systems still value the fifteen-minute ‘med rec’ visit over the hour spent listening to war stories.

The heart monitor’s steady rhythm underscored his words as he began unpacking memories older than the Medicare system paying for this hospitalization. Outside the window, a Minnesota blizzard swirled, but in this space between coughs and confession, between dying and dignity, we’d found common ground far from oncology protocols or hospice eligibility guidelines.

Hammers and Howitzers

The dim glow of the night light caught the tremor in his hands as he reached for the water glass. Between labored breaths, his voice gained unexpected strength when describing the Pacific islands—not as battlefields, but as construction sites where his engineering battalion hammered together hangars under enemy fire.

Monsoon Winds and Marine Plywood

His fingers traced invisible blueprints in the air while recounting how typhoons would rip through their half-built structures. “We learned to notch the joints deeper after losing three hangars in one storm,” he said, the technical precision cutting through his morphine haze. The 1944 Saipan campaign came alive through details like the smell of salt-rotted timber and the way they’d barter C-ration tins with locals for woven palm frond roofing.

A Combat Engineer’s Toolkit

The war taught him resourcefulness that would later build Missouri suburbs. His eyes brightened describing the canvas tool belt he wore—still kept in his attic—with its compartments for nails salvaged from bombed-out Japanese bunkers. Historical records show his 73rd Engineer Battalion moved 12,000 cubic yards of coral rubble to level airstrips while suffering 22% casualties from both combat and tropical diseases.

A coughing spell interrupted his story. As I adjusted his oxygen flow, his hand gripped mine with surprising force. “Those islands… we left more than sewage systems there,” he whispered. The heart monitor’s steady beep underscored what went unsaid—how young men who poured concrete under mortar fire carried those memories like unhealed wounds.

Between Battles and Blueprints

The narrative pivoted seamlessly between past and present. One moment detailing how they repurposed artillery shell casings as pipe fittings, the next observing how modern hospital rooms lacked such ingenuity. “Back then,” he wheezed with dark humor, “we made do with what we had. Now you docs got machines that go ping but can’t stop the damn cancer.”

Through these fragments emerged an alternate WWII history—not of generals and beachheads, but of enlisted men solving problems with slide rules and sweat. The same hands now trembling against hospital sheets had once jury-rigged freshwater distillation systems using wrecked jeep radiators. That contrast—between the vigorous problem-solver of 1944 and the frail man fighting for breath—hung heavily in the antiseptic air.

Blueprints for a Future Unseen

The hospital room hummed with the rhythmic beeping of monitors, but the old man’s voice cut through the mechanical sounds with surprising clarity. His fingers, now gnarled by age and illness, traced invisible blueprints in the air as he spoke. “We knew what was coming after the war,” he said between measured breaths. “All those boys coming home—they’d need roofs over their heads, yards for their kids.”

Visions in the Midst of Chaos

In the dim glow of the night light, I watched his face transform as he described his wartime epiphanies. Between constructing hangars on Pacific islands and digging sewage systems under enemy fire, the young engineer had developed an uncanny foresight about postwar America. “You didn’t need a crystal ball,” he chuckled, triggering a brief coughing spell. “Just count the sweethearts’ letters in any soldier’s pack.”

His predictions carried the weight of lived experience:

- The explosive demand for suburban housing (“Every Joe would want his own patch of grass”)

- The coming baby boom (“We joked the real construction would happen in bedrooms”)

- The shift in consumer priorities (“First a refrigerator, then maybe college for the kids”)

Between Past and Present

The heart monitor’s sudden alarm jerked us both back to the present. As I adjusted his oxygen flow, his trembling hand grasped mine with unexpected strength. “Doc, you know what’s funny?” he whispered. “We built airfields for bombers, but what changed America were all those little houses with picket fences.”

Historical data would later confirm his wartime observations—the U.S. Census Bureau recorded over 13 million housing units constructed between 1946-1950, while the postwar baby boom added 76 million new Americans by 1964. But in that moment, what struck me wasn’t the accuracy of his predictions, but the vividness of his memories despite his failing body.

The Architect’s Regret

A shadow crossed his face as he confessed one unfulfilled vision. “Never got to build my own house,” he murmured, eyes fixed on the acoustic tile ceiling. “Kept putting it off for tomorrows that…” His sentence dissolved into another cough, leaving the thought unfinished.

The heart monitor’s steady pulse filled the silence as I recognized this moment’s gift—not just a history lesson, but a window into how terminal patients often review their lives through the lens of unfinished dreams. In palliative care training, we call this “life review,” a psychological process where patients naturally seek meaning and closure.

The Blueprint of a Life

As his breathing stabilized, he offered me a weathered smile. “Still, those blueprints we drew in the mud? They became real towns. That’s something.” The simple statement carried profound weight—an acknowledgment that while individual dreams might go unbuilt, collective visions shape history.

The blip of an incoming text on my hospital pager threatened to break the spell, but his story had anchored me to what matters most in end-of-life care: bearing witness to a person’s entire landscape of memories, not just their failing organs. In that dimly lit room, between the beeps and the breaths, we weren’t just doctor and patient—we were time travelers walking through the blueprints of a life well-lived.

The Last Patrol

The hospital corridor lights dimmed to night mode as I finished charting. On my screen, the patient’s record read simply: Room 412 – Lung CA, Stage IV – DNR. A clinical shorthand that reduced ninety years of lived experience to a three-letter acronym. Outside his door, I paused to watch the cardiac monitor’s green line spike and trough in relentless rhythm, realizing with sudden clarity that this waveform would soon flatline—taking with it memories of Pacific typhoons and postwar housing predictions that had proven eerily accurate.

The Stories Behind the Numbers

Modern medicine trains us to think in bullet points. His admission note had precisely seven: smoking history, biopsy results, metastatic sites, creatinine level, code status, next-of-kin contact, and my pager number. Yet in those stolen midnight hours, I’d learned about the canvas tool belt he wore as an Army engineer, how he bartered C-rations for coconut milk on Saipan, and why he insisted postwar suburbs would need wider sewer pipes. The EMR had fields for allergies and advance directives, but nowhere to document that he could still smell the brine of the Pacific when he closed his eyes.

When Technology Can’t Listen

The computer beeped impatiently, reminding me to complete the discharge summary for another patient. Our electronic systems prioritize measurable data—lab values, medication doses, vital signs—while quietly eroding the space for narrative medicine. I thought of studies showing palliative care physicians spend 60% of clinic time staring at screens rather than patients. The very EHR designed to coordinate care had become a barrier to the human connection that makes end-of-life conversations meaningful.

A Night Light for the Living

Before leaving, I reached for the wall switch behind his bed. The overhead fluorescents died with a click, but I left the bathroom night light glowing—not for him, who no longer feared darkness, but for myself. That tiny bulb illuminated more than linoleum; it revealed how much we lose when efficiency overrides presence. Somewhere between the war stories and the wheezing breaths, this dying engineer had rebuilt something in me: the understanding that true palliative care begins when we mute the monitors to hear the person.

The wheelchair outside Room 412 sat empty in the morning light when I returned—its vinyl seat still holding the impression of a life that had slipped away quietly, like tide retreating from one of his Pacific beaches.

When Death Files Its Report

The hospital corridor stretched before me in the pale morning light, its polished floors reflecting the gurneys and wheelchairs parked along the walls. A janitor moved slowly with his mop bucket, the squeak of rubber wheels marking time like a metronome. Somewhere beyond the stairwell doors, the day shift nurses were exchanging reports in brisk tones, their laughter occasionally piercing through the hum of the ventilation system.

I paused by the window, letting the sunrise warm my face. The oncology ward never truly sleeps – even now, the beeping of IV pumps and the occasional call light formed a dissonant symphony with the waking city outside. My fingers absently traced the edges of the chart I carried, its pages holding the clinical summary of the night’s events: vitals, medication adjustments, progress notes. But nowhere in this neatly typed documentation could one find the weight of a handshake from a man who once built airfields under Japanese bombardment, or the particular cadence of a laugh that remembered USO dances in 1943.

Medical school had trained me to recognize the textbook signs of impending death – the Cheyne-Stokes respirations, the mottled skin, the decreased urine output. Yet no lecture had prepared me for these final chapters where life reveals itself not through lab values, but through stories told between oxygen tank changes. That Missouri veteran’s tales of improvising sewer systems on Pacific atolls now felt as vital to my medical education as any pharmacology textbook.

A food service cart rattled by, its plastic lids clattering like distant artillery fire. The metaphor didn’t escape me – how the routines of hospital life continued unabated while individual worlds ended quietly behind numbered doors. We documented the facts of dying with such precision: time of death, presumed cause, next of kin notified. But who records the way a man’s eyes still spark when describing his first postwar Chevrolet, or how his voice drops conspiratorially when sharing a seventy-year-old barracks joke?

My pager buzzed, summoning me to morning rounds. As I turned from the window, my shadow merged with those of other white-coated figures moving through the hallway. We were all temporary custodians of these stories, I realized – the construction foremen turned patients, the Rosie the Riveters in chemotherapy chairs. Each shift change, each signed-out chart represented another fragile thread in medicine’s unwritten archive of lived history.

The question lingered like the scent of disinfectant in the elevator: When death comes filing its report, who keeps the stories? Perhaps the answer lies not in our electronic medical records, but in the spaces between them – in the night light confessions, the medication-delayed reminiscences, the truths spoken when vital signs become secondary to voice itself.

Maybe healing, in its fullest sense, requires us to be not just clinicians but chroniclers – to honor what pulses beneath the numbers, to preserve not only how lives end, but how they were lived.